"I lost my home," Vera von Lehndorff once said, "but lost childhood is a better description." When her father was executed on September 4, 1944, she was five years old. Her sister Eleonore, "Nona," was six and a half, and Gabriele was two. Catharina was only 19 days old; she was born in the Torgau prison hospital. The Nazis had taken the girls and their mother Gottliebe into custody, a practice known in German as "Sippenhaft” or “kin liability". It was a traumatic time and was by no means over when the war ended in 1945.

Text

“We don’t remember ,” says Gabriele von Plotho. She and her sister Catharina, “the little ones”, as they were called in the family, have come back to Steinort, this time without their sister Vera.1 Nona died in 2018, leaving only three Lehndorff daughters.

For some time now, the descendants of Heinrich and Gottliebe von Lehndorff have been meeting in Masuria. Daughters, grandchildren and great-grandchildren, relatives from the Dönhoff line. They spend short summer vacations together here; in the evenings, they are guests of honor at the castle festival.

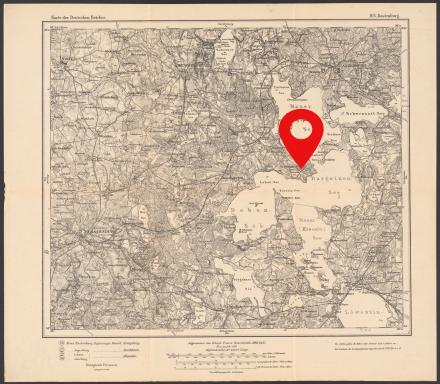

Sztynort

deu. Steinort, deu. Groß Steinort

The village of Sztynort is located in the north of the Masurian Lake District on the Jez Peninsula between Jezioro Mamry, Jezioro Dargin and Jezioro Dobskie. Until 1928 the village was called Groß Steinort, then Steinort.

For some time now, the descendants of Heinrich and Gottliebe von Lehndorff have been meeting in Masuria. Daughters, grandchildren and great-grandchildren, relatives from the Dönhoff line. They spend short summer vacations together here; in the evenings, they are guests of honor at the castle festival.

Castle festival 2021. Ulla Lachauer, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Castle festival 2021. Ulla Lachauer, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Text

"What are we going to tell you?" Gabriele von Plotho smiles. "Our mother Gottliebe didn't talk much about the past," adds her sister Catharina. "Of course, as children, we picked up on her melancholy."

Our meeting is brief but warm-hearted. It’s a gray day, outside the window of the café the swallows shoot past non-stop at lightning speed, disappearing in the direction of Mauersee.

"We only know our father Heinrich from stories. Mother once said that when he came into the room, he glowed." This glow has clearly accompanied the orphaned family to this day. "His love of life must be in our DNA."

Sentences, hints that don't become stories.

Karin von Dönhoff, her older cousin, will later describe2 how Heinrich von Lehndorff once threw her into the air, "as one does with children." The last lord of Steinort Castle was her godfather. For Christmas, she remembers, he gave her a white goat with a small carriage – that was in 1942 or the year after.

Our meeting is brief but warm-hearted. It’s a gray day, outside the window of the café the swallows shoot past non-stop at lightning speed, disappearing in the direction of Mauersee.

"We only know our father Heinrich from stories. Mother once said that when he came into the room, he glowed." This glow has clearly accompanied the orphaned family to this day. "His love of life must be in our DNA."

Sentences, hints that don't become stories.

Karin von Dönhoff, her older cousin, will later describe2 how Heinrich von Lehndorff once threw her into the air, "as one does with children." The last lord of Steinort Castle was her godfather. For Christmas, she remembers, he gave her a white goat with a small carriage – that was in 1942 or the year after.

Countess Karin von Dönhoff, born 1936, in Sztynort. Ulla Lachauer, Free access - no reuse

Countess Karin von Dönhoff, born 1936, in Sztynort. Ulla Lachauer, Free access - no reuse

Text

In the archives of the East Prussian State Museum3 there is a photo album that gives an insight into life at Steinort Castle at that time. Gottliebe von Lehndorff created it in 1937, when her first child was born.

Gottliebe with her daughter Eleonore, or “Nona” for short. Ostpreußisches Landesmuseum, Free access - no reuse

Gottliebe with her daughter Eleonore, or “Nona” for short. Ostpreußisches Landesmuseum, Free access - no reuse

Nona and the second eldest daughter Vera. Ostpreußisches Landesmuseum, Free access - no reuse

Nona and the second eldest daughter Vera. Ostpreußisches Landesmuseum, Free access - no reuse

Text

It shows the young mother in the ambience of the castle and its extensive grounds. The city-dweller Gottliebe has clearly found a home in the world of her husband. There’s a picture of Nona, then one of Vera on a blanket. The two sisters in the sandbox, on a rocking horse, later we see them on ponies. In fancy double-breasted coats, a hunting dog on a leash.

Notes written in ink pen by their mother tell of teething, first steps. Of Vera's birth, she notes, "She weighed 6 ½ pounds, was very long and thin. Especially noticeable were her long feet." Eleonore, it continues, "was very surprised at her little sister and at first thought she was a little dog. As soon as I started to breastfeed Vera, she became jealous and clearly wanted some, too."

These documents show a sheltered, privileged childhood. The beloved nanny, Fräulein Gräber, also features as part of everyday life.

On the last pages of the album the family’s vacation at the Baltic Sea in 1943 are immortalized. The father is there, it is the summer before the Hitler assassination plot. Heinrich von Lehndorff has long been involved in the conspiracy, living a dangerous double life with his wife.

Notes written in ink pen by their mother tell of teething, first steps. Of Vera's birth, she notes, "She weighed 6 ½ pounds, was very long and thin. Especially noticeable were her long feet." Eleonore, it continues, "was very surprised at her little sister and at first thought she was a little dog. As soon as I started to breastfeed Vera, she became jealous and clearly wanted some, too."

These documents show a sheltered, privileged childhood. The beloved nanny, Fräulein Gräber, also features as part of everyday life.

On the last pages of the album the family’s vacation at the Baltic Sea in 1943 are immortalized. The father is there, it is the summer before the Hitler assassination plot. Heinrich von Lehndorff has long been involved in the conspiracy, living a dangerous double life with his wife.

A vacation at the Baltic Sea in 1943, Heinrich von Lehndorff with Vera and Nona. Familienarchiv Lehndorff, Free access - no reuse

A vacation at the Baltic Sea in 1943, Heinrich von Lehndorff with Vera and Nona. Familienarchiv Lehndorff, Free access - no reuse

Text

Who took the photos? Gabriele, the third daughter, does not feature in this album. After her mother's death, Gabriele von Plotho says, she found baby photos of herself in a chest. "That moved me a lot."

We have Vera von Lehndorff to thank for more detailed descriptions of her childhood years.4 Born in 1939 and known worldwide as "Veruschka", she took part in a long biographical interview – with author Jörn Jakob Rohwer – late in her career.

We have Vera von Lehndorff to thank for more detailed descriptions of her childhood years.4 Born in 1939 and known worldwide as "Veruschka", she took part in a long biographical interview – with author Jörn Jakob Rohwer – late in her career.

Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop in the grounds of Steinort Castle with Vera and Nona, 1942. Familienarchiv Lehndorff, Free access - no reuse

Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop in the grounds of Steinort Castle with Vera and Nona, 1942. Familienarchiv Lehndorff, Free access - no reuse

Text

She remembered Foreign Minister von Ribbentrop, the uninvited guest who resided in the west wing of the castle and liked to have his picture taken with the Count's family. She and Nona would be put in little white dresses and he would take them by the hand. Once Ribbentrop gave them two ponies; to the girls he was "the dear kind uncle who gave us presents."5 As a grown woman she looked at these staged photos with horror.

Text

Vera von Lehndorff took on the role of chronicler in her generation. She would later put these fragments of images into larger contexts – spring in the park and the nearby lake, the canary Hansi. He was allowed to come along when the three girls were sent with their governess to stay with their grandfather in Graditz in July 1944.

The memory of saying goodbye to her father has remained with her, clear and painful. "We were already on the train." He was outside, looking in through the window. "His look was so unfamiliar to me, so serious." She has never forgotten his face at that moment.

In a photo taken a few weeks earlier, Vera is sitting on a swing, laughing. Above her, her father, tall and upright, appears lost in his thoughts.

"I loved my father very much. With him I experienced a feeling of real tenderness."

The memory of saying goodbye to her father has remained with her, clear and painful. "We were already on the train." He was outside, looking in through the window. "His look was so unfamiliar to me, so serious." She has never forgotten his face at that moment.

In a photo taken a few weeks earlier, Vera is sitting on a swing, laughing. Above her, her father, tall and upright, appears lost in his thoughts.

"I loved my father very much. With him I experienced a feeling of real tenderness."

Vera and her father Heinrich von Lehndorff in the spring or summer of 1944. Familienarchiv Lehndorff, Free access - no reuse

Vera and her father Heinrich von Lehndorff in the spring or summer of 1944. Familienarchiv Lehndorff, Free access - no reuse

$de=Kinderheimat. Landschaft bei Steinort. Familienarchiv Lehndorff, Free access - no reuse

$de=Kinderheimat. Landschaft bei Steinort. Familienarchiv Lehndorff, Free access - no reuse

Text

On August 25, 1944, in the middle of the night, Nona, Vera and Gabriele were torn from their beds in their grandfather's house. They were taken to Bad Sachsa in the Harz mountains, to the Borntal Nazi children's home, where the children of those involved in the events of July 20 were interned. Here they experienced three months of fear, abandonment, and harassment. It was a nightmare, a radical break with their previous lives.

Gabriele von Plotho hints that Bad Sachsa still weighs on her today. She was two at the time. Her five-year-old sister Vera tried to protect her.

In December 1944, the girls were allowed to visit their grandmother in the Uckermark. There they saw their mother again, holding their new little sister Catharina.

Gabriele von Plotho hints that Bad Sachsa still weighs on her today. She was two at the time. Her five-year-old sister Vera tried to protect her.

In December 1944, the girls were allowed to visit their grandmother in the Uckermark. There they saw their mother again, holding their new little sister Catharina.

The Borntal children’s home in Bad Sachsa. Collection Ralph Boehm. Stadtarchiv Bad Sachsa, Free access - no reuse

The Borntal children’s home in Bad Sachsa. Collection Ralph Boehm. Stadtarchiv Bad Sachsa, Free access - no reuse

The Borntal children’s home in Bad Sachsa, dormitory. Collection Ralph Boehm. Stadtarchiv Bad Sachsa, Free access - no reuse

The Borntal children’s home in Bad Sachsa, dormitory. Collection Ralph Boehm. Stadtarchiv Bad Sachsa, Free access - no reuse

Text

In January 1945, they fled together from the Red Army in the direction of Bremen. They made a stopover in Berlin – SS leader Wolff had summoned Gottliebe to the Hotel Adlon to hand over her husband's farewell letter6.

After the end of the war, she and her daughters found shelter and peace for a few years with the von Alvensleben family, friends of hers, at "Fichtenhof", not far from Bremen. At first, the widow seemed composed, determined to bring "a new meaning" to her life, as she wrote to the poet Ricarda Huch in July 1946.7

After the end of the war, she and her daughters found shelter and peace for a few years with the von Alvensleben family, friends of hers, at "Fichtenhof", not far from Bremen. At first, the widow seemed composed, determined to bring "a new meaning" to her life, as she wrote to the poet Ricarda Huch in July 1946.7

Text

In the late 1940s, Gottliebe von Lehndorff suffered an extended bout of depression and sadness. The faithful Fräulein Gräber took care of the children. At times, they were sent away to children's homes, boarding schools, foster families. "My mother did what she could, but she couldn’t give us love," concludes Vera von Lehndorff in retrospect.

In the late 1940s, Gottliebe von Lehndorff suffered an extended bout of depression and sadness. The faithful Fräulein Gräber took care of the children. At times, they were sent away to children's homes, boarding schools, foster families. "My mother did what she could, but she couldn’t give us love," concludes Vera von Lehndorff in retrospect.

In the late 1940s, Gottliebe von Lehndorff suffered an extended bout of depression and sadness. The faithful Fräulein Gräber took care of the children. At times, they were sent away to children's homes, boarding schools, foster families. "My mother did what she could, but she couldn’t give us love," concludes Vera von Lehndorff in retrospect.

Gottliebe Lehndorff in 1949 with her daughters, from left Nona, Gabriele, Catharina, Vera and the dog Seppi. Familienarchiv Lehndorff, Free access - no reuse

Gottliebe Lehndorff in 1949 with her daughters, from left Nona, Gabriele, Catharina, Vera and the dog Seppi. Familienarchiv Lehndorff, Free access - no reuse

Text

One day, Gottliebe von Lehndorff read to her daughters their father's farewell letter. A tearful afternoon. Much later – in the early 1990s, in Paris – Vera reflected on the letter with a therapist and found comfort in it.

Vera in 1952. Familienarchiv Lehndorff, Free access - no reuse

Vera in 1952. Familienarchiv Lehndorff, Free access - no reuse

Text

She was aware early on that there were millions of people like her. The Lehndorffs were not the only ones to have lost their home. The nobility no longer had any social significance. She had to find her own way. Inspired by the freedom movements of the 1960s, she transformed herself into "Veruschka.”

Under this name, the thin, sad girl with the big feet became the first German supermodel. The "most beautiful woman in the world," photographer Richard Avedon called her. She herself spoke of modeling as "a pleasant kind of escape."8 She loved living in Rome, Paris and New York.

Under this name, the thin, sad girl with the big feet became the first German supermodel. The "most beautiful woman in the world," photographer Richard Avedon called her. She herself spoke of modeling as "a pleasant kind of escape."8 She loved living in Rome, Paris and New York.

Gottliebe von Lehndorff and her daughters Vera, Nona and Catharina, 1961. Ostpreußisches Landesmuseum, Free access - no reuse

Gottliebe von Lehndorff and her daughters Vera, Nona and Catharina, 1961. Ostpreußisches Landesmuseum, Free access - no reuse

Text

Each of the Lehndorff daughters fought in their own way to make a life for themselves. The rebellious Nona left home early and married Jan von Haeften in 1957. His father had also been executed at Plötzensee. She later joined forces with Wieland Wagner's son Wolf-Siegfried and began a new life with him in Mallorca.

All four became self-willed, emancipated women: Catharina is a trained goldsmith, and became famous for creating elaborate leather belts. Gabriele von Plotho opted for the healing arts, working as a homeopath in Munich. Her father Heinrich, who would have loved to have sons, would have been proud of them all.

All four became self-willed, emancipated women: Catharina is a trained goldsmith, and became famous for creating elaborate leather belts. Gabriele von Plotho opted for the healing arts, working as a homeopath in Munich. Her father Heinrich, who would have loved to have sons, would have been proud of them all.

Text

In 1977, Gottliebe von Lehndorff traveled to Masuria again for the first time since the war. Gabriele and her husband Armin Gebhard von Plotho accompanied her. "We were afraid that she would have a breakdown. But that didn't happen," Gabriele von Plotho tells us in August 2021 in Sztynort.9

The landscape around Mauersee. Ulla Lachauer, Free access - no reuse

The landscape around Mauersee. Ulla Lachauer, Free access - no reuse

Inauguration of the memorial stone commemorating the 100th birthday of Heinrich von Lehndorff, 2009. Kilian Heck, Free access - no reuse

Inauguration of the memorial stone commemorating the 100th birthday of Heinrich von Lehndorff, 2009. Kilian Heck, Free access - no reuse

Text

Gabriele von Plotho remembers being enchanted by the landscape, the vast expanses. Thirty years later, the Lehndorffs rediscovered their former family home. The turning point was the ceremonial dedication of a memorial stone on the 100th birthday of her father in 2009. At last, the family, who had dispersed far and wide, had a place to return to and mourn. Vera von Lehndorff spoke to many of the guests, both visiting and local.

Perhaps there was a future for the castle, which now belonged to the Polish-German Foundation. Urgent restoration work began. Antje Vollmer's book "Doppelleben" was published, telling the story of Heinrich and Gottliebe Lehndorff. A court order stipulated that a part of the castle inventory be returned to their descendants. A promising windfall! And a catalyst. The four sisters suddenly found themselves faced with an important task.

Perhaps there was a future for the castle, which now belonged to the Polish-German Foundation. Urgent restoration work began. Antje Vollmer's book "Doppelleben" was published, telling the story of Heinrich and Gottliebe Lehndorff. A court order stipulated that a part of the castle inventory be returned to their descendants. A promising windfall! And a catalyst. The four sisters suddenly found themselves faced with an important task.

Text

Within the framework of the "Lehndorff Society Steinort," they have been working to support the revival of the castle. Their wish is to keep alive the memory of July 20 and the resistance fighters. However, they are adamant that the focus should not be on the noble family, but on the fate of Poles and Germans in the region.

"Something has to be done for the young people here," says Gabriele von Plotho. "We probably won't live to see the castle finished." Both sisters, on this day in August 2021, are sure of that.

Yesterday, they took a walk through the old oak avenue behind the castle. I wonder if the tree that was planted when Gabriele was born is still standing. That was the tradition: for each new Lehndorff child a young oak tree. Gabriele was the last child to be born in the castle – in August 1942.

"Something has to be done for the young people here," says Gabriele von Plotho. "We probably won't live to see the castle finished." Both sisters, on this day in August 2021, are sure of that.

Yesterday, they took a walk through the old oak avenue behind the castle. I wonder if the tree that was planted when Gabriele was born is still standing. That was the tradition: for each new Lehndorff child a young oak tree. Gabriele was the last child to be born in the castle – in August 1942.

Nona and Vera in the oak avenue, early 1940s. Ostpreußisches Landesmuseum, Free access - no reuse

Nona and Vera in the oak avenue, early 1940s. Ostpreußisches Landesmuseum, Free access - no reuse

Text

"Walking through the avenue, this flash of anger came over me," says Catharina Kappelhoff-Wulff. "For a moment I thought, why couldn't we grow up here?" Gabriele von Plotho felt differently. "For me, it's all long gone. Far away."

Text

English translation: William Connor