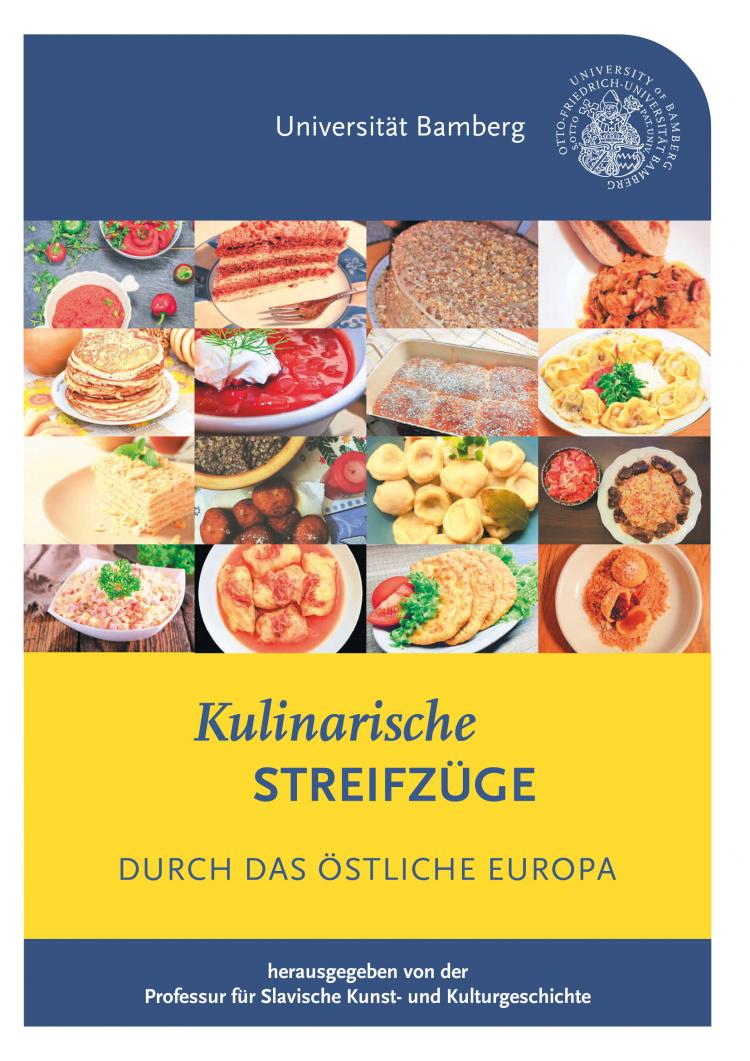

Every recipe tells a story – be it that of one’s own family, social group, region, of nation states or whole empires. A particular dish is thus always both a symbol and an expression of cultural concepts. A recipe booklet compiled by students at the University of Bamberg looks at “Culinary Forays Into Eastern Europe” (Kulinarische Streifzüge durch das östliche Europa) and brings together a series of recipes of cultural and historical interest. Below is an especially delicious sample.

Mini-Napoleons – a new take on a classic

Text

Mini-Napoleons are a minor variation on the classic Torte Napoleon, which today is one of the most popular Russian desserts. The tartlet is made up of many layers of puff pastry, filled with delicious crème pâtissière. It is often served on festive occasions such as weddings, birthdays, anniversaries or at New Year’s celebrations. Similar puff pastry recipes have existed in Western Europe for more than 200 years. The oldest of these come from France where the cakes are known as mille-feuille, that is, “a thousand sheets, layers, or leaves.” In Poland, too, variations of this recipe known as Napoleonka are among the best-loved cakes. Here the puff pastry forms the upper and lower layers of the cake, with a thick layer of crème pâtissière in the middle.

French cuisine had a significant influence on Russian cuisine and eating habits, and this was quite openly celebrated. Between 1862 and 1912, the “Week of French Culinary Art” would take place every ten years or so, celebrating French cuisine as well as the Franco–Russian peace treaty of 1812. These special culinary festivals were attended by some prominent guests and notable intellectuals, including the writers Ivan Turgenev (1818–1883) and Anton Chekhov (1860–1904).

Why Napoleon? Napoleon Bonaparte’s Russian Campaign, 1812

Text

Both the Torte Napoleon and the week of culinary art commemorate the most important military and political achievement of the Russian Empire at the start of the 19th century, which became an integral part of Russian cultural memory: victory over the French army led by Emperor Napoleon (1769–1821) and the defeat of his Russian Campaign.

Both empires had actually signed the Treaty of Tilsit in 1807, and this allowed both rulers, Emperor Napoleon and Tsar Alexander I (1777–1825), to assert their own interests and reach further secret agreements. But this peace was not to last. One of the central conditions to the treaty was Russia’s participation in the Continental Blockade, which involved a large-scale embargo of Britain by land and sea and which was to be implemented across the whole of the French sphere of influence. However, this approach did not go down well in the Russian Empire, provoking popular resistance and causing economic problems. Russia recommenced its trade relations with Britain as early as 1811. The two countries that were actually at war with one another also experienced a political rapprochement, while the conflict between France and Russia was reignited. The French emperor decided to invaded the Tsarist empire. The whole of continental Europe had already come under Napoleon’s control by 1812, but on 24 June 1812 he started a new war, hoping for a quick win thanks to his powerful army. After some initial successes on the French side, the campaign turned into a major military catastrophe: countless solders from the Grande Armée lost their lives and their army was ultimately expelled from Russian territory completely.

A victory cake

Text

Patriotic attempts to bring about a new flowering in Russian cuisine in the years that followed were less successful. Too much knowledge had been lost; information on traditional Russian dishes was very difficult to come by and only rarely documented. Food culture in Russia continued to be characterized by strong influences from other countries, notably France.

The practice of naming dishes in honour of or with reference to historical figures goes back to the reign of Catherine II (1729–1796). This is also the origin of the Torte Napoleon, which, according to legend, was created in 1912 for the centenary of the victory over Napoleon. Originally the cake was triangular, a visual reference to Napoleon’s famous bicorne hat.

Method

Text

And this is how you can easily prepare them:

Ingredients for 24 pieces:

- 16 puff pastry squares

- 180 g sugar

- 500 ml milk

- 100 g softened butter

- 3 tbsp flour

- 2 egg yolks

- 2 packets vanilla sugar

1 Using a hand-held mixer, whisk the two egg yolks in a saucepan for five minutes, gradually adding the sugar. Add the flour, whisking continuously, then add the milk a little at a time.

2 Set the saucepan on a medium heat and continue to beat with a whisk until the mixture comes to the boil and develops a creamy consistency. Remove the saucepan from the heat and allow the mixture to cool until it is just lukewarm. Stir every 15 minutes to prevent lumps from forming.

3 In the meantime, take the puff pastry out of the refrigerator and allow to it to come up to room temperature for 10 minutes. Cut the puff pastry squares in half and arrange them on a baking tray with plenty of space between them. Bake the puff pastry until golden brown (c. 10 minutes in the middle of a preheated oven at 200° C).

4 Add the softened butter and the vanilla sugar to the egg yolk mixture and stir thoroughly. Allow the crème pâtissière to cool completely, since it must not touch the puff pastry while it is still warm.

5 Crumble up eight of the 32 baked puff pastry squares. Cover the tops and sides of the remaining squares with the crème pâtissière and sprinkle them with the pastry crumbs. Store in the refrigerator until required.

A Hovhannisjan family recipe.

Hungry for more Culinary Forays Into Eastern Europe?

Text

Students at the Institute for Slavic Studies, University of Bamberg, compiled a recipe booklet as part of their seminar on food culture in order to answer the question: “What do Slavic cuisines taste like?”

“Hearty. Greasy. Meat-dominated!” was what the students first expected. But the answer is not so simple. The booklet, made up primarily of family recipes contributed by the students, includes numerous classics from Slavic cuisine(s) such as borscht, pelmeni, ajvar, bigos or Olivier salad. But there are also sweet recipes such as buchteln (sweet rolls), Torte Napoleon, festive pryaniki (Lebkuchen) and plum dumplings. Short accompanying texts provide not only insight into the broad spectrum of topics in the study of food cultures, but also information on the cultural and historical background to the recipes themselves (to entertain you while you wait for your food to cook). Obviously, it was only possible to give a small taste of the diversity of Slavic cuisine(s), but the idea was to whet the reader’s appetite.

The recipe brochure can be downloaded for free here:

https://fis.uni-bamberg.de/handle/uniba/49731

“Hearty. Greasy. Meat-dominated!” was what the students first expected. But the answer is not so simple. The booklet, made up primarily of family recipes contributed by the students, includes numerous classics from Slavic cuisine(s) such as borscht, pelmeni, ajvar, bigos or Olivier salad. But there are also sweet recipes such as buchteln (sweet rolls), Torte Napoleon, festive pryaniki (Lebkuchen) and plum dumplings. Short accompanying texts provide not only insight into the broad spectrum of topics in the study of food cultures, but also information on the cultural and historical background to the recipes themselves (to entertain you while you wait for your food to cook). Obviously, it was only possible to give a small taste of the diversity of Slavic cuisine(s), but the idea was to whet the reader’s appetite.

The recipe brochure can be downloaded for free here:

https://fis.uni-bamberg.de/handle/uniba/49731

Enjoy! Приятного аппетита! Smacznego! Dobrou chut‘! Dobar tek! Пријатно!

Title page of the recipe booklet, “Kulinarische Streifzüge durch das östliche Europa” („Culinary Forays Into Eastern Europe“). Volker Ehnes (2021), Free access - no reuse

Title page of the recipe booklet, “Kulinarische Streifzüge durch das östliche Europa” („Culinary Forays Into Eastern Europe“). Volker Ehnes (2021), Free access - no reuse

Text

English translation: Kate Sotejeff-Wilson