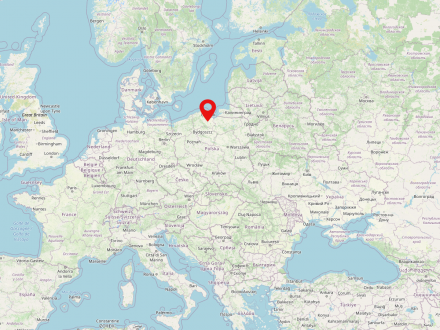

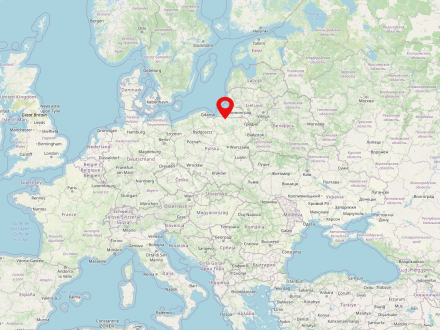

Poland is a state in Central Eastern Europe and is home to approximately 38 million people. The country is the sixth largest member state of the European Union. The capital and biggest city of Poland is Warsaw. Poland is made up of 16 voivodships. The largest river in the country is the Vistula (Polish: Wisła).

West Prussia is a historical region in present-day northern Poland. The region fell to Prussia as a result of the first partition of Poland-Lithuania in 1772 and received its name from the province of the same name formed by Frederick II in 1775, which also included parts of the historical landscapes of Greater Poland, Pomerania, Pomesania and Kulmerland. The Prussian province lasted in changing borders until the early 20th century. After World War I, parts fell to the Second Polish Republic, founded in 1918. The largest cities in West Prussia include Gdansk (Polish: Gdańsk, today Pomeranian Voivodeship), Elbląg (Polish: Elbląg, today Warmia-Masuria Voivodeship), and Thorn (Polish: Toruń, today Kujawsko-Pomeranian Voivodeship).

The historical province of Poznan was situated in eastern Prussia from 1815 to 1920. Currently, the territory of the former province is entirely in Poland. The capital was the city of the same name, Posen (present Poznań). About 2 million people inhabited the area.

'We can also burn our furniture if necessary,' she added. I shuddered at the idea. I imagined her dismantling the beautiful bookcase and burning it for us, piece by piece. I didn't doubt for a second that she would do it. Our mother was a lioness and she would fight for us. So we could rest easy. A quarter of a century later, the wood stove was moved to the basement – it took her that long to fully trust that peace was here to stay. The stove remained down there until the house was cleared out after my mother's death. Stories of flight and expulsion, of people at war, of the years of hardship after the war accompanied us throughout our childhood years. We knew some of our mother's stories so well that we could join in when she told them.

East Prussia is the name of the former most eastern Prussian province, which existed until 1945 and whose extent (regardless of historically slightly changing border courses) roughly corresponds to the historical landscape of Prussia. The name was first used in the second half of the 18th century, when, in addition to the Duchy of Prussia with its capital Königsberg, which had been promoted to a kingdom in 1701, other previously Polish territories in the west (for example, the so-called Prussia Royal Share with Warmia and Pomerania) were added to Brandenburg-Prussia and formed the new province of West Prussia.

Nowadays, the territory of the former Prussian province belongs mainly to Russia (Kaliningrad Oblast) and Poland (Warmia-Masuria Voivodeship). The former so-called Memelland (also Memelgebiet, lit. Klaipėdos kraštas) first became part of Lithuania in 1920 and again from 1945.

Michael Schwartze carefully takes the spoon in his hand, almost as if it could crumble into dust at any moment. His special appreciation of this object is expressed in how carefully he handles the little piece of sheet metal, which weighs only a few grams. "The spoon probably saved my father's life during his captivity in the war," Schwartze says thoughtfully, recalling the few details that his father, Theo Schwartze, who died on February 24, 2014, once recounted about the difficult years in Russia. His father was at war on the Eastern Front and was taken prisoner in Borissow near Minsk in 1944. Most of the time only a thin soup was provided, which his father had to eat using a can full of holes. "A fellow prisoner of my father was assigned to a workshop in the labor camp. As far as I know, he came from Ahlen. And he made my father this spoon so that none of the precious food was spilled anymore," Schwartze reports. "It was freely given – a gesture my father could not reciprocate at that moment."