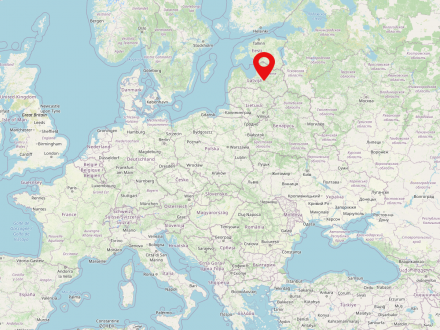

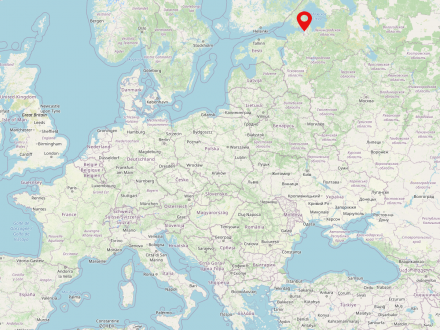

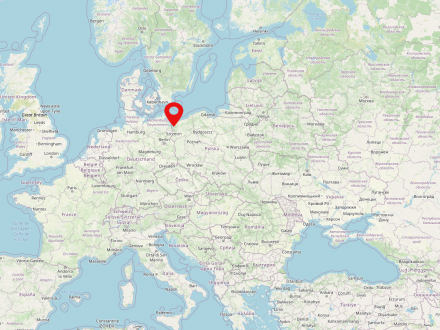

Estonia is a country in north-eastern Europe and geographically it belongs to the Baltic States. The country is inhabited by about 1.3 million people and borders Latvia, Russia and the Baltic Sea. The most populated city and capital at the same time is Tallinn. Estonia has been independent since 1991 and is a member of the European Union.

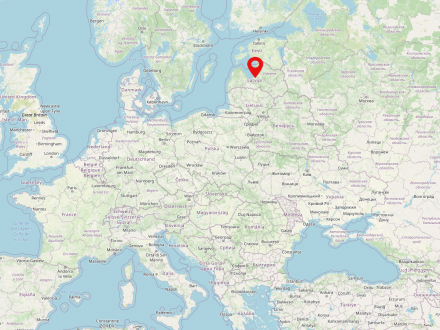

Latvia is a Baltic state in the north-east of Europe and is home to about 1.9 million inhabitants. The capital of the country is Riga. The state borders in the west on the Baltic Sea and on the states of Lithuania, Estonia, Russia and Belarus. Latvia has been a member of the EU since 01.05.2004 and only became independent in the 19th century.

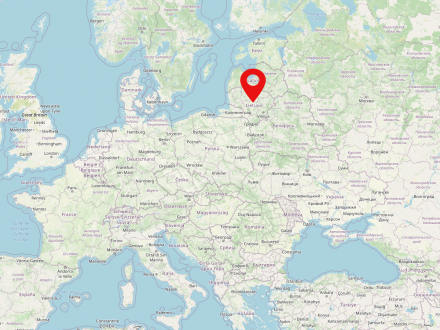

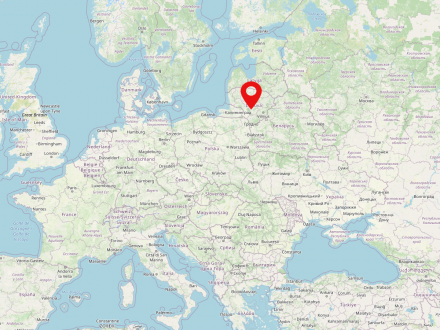

Lithuania is a Baltic state in northeastern Europe and is home to approximately 2.8 million people. Vilnius is the capital and most populous city of Lithuania. The country borders the Baltic Sea, Poland, Belarus, Russia and Latvia. Lithuania only gained independence in 1918, which the country reclaimed in 1990 after several decades of incorporation into the Soviet Union.

Vilnius is the capital and most populous city of Lithuania. It is located in the southeastern part of the country at the mouth of the eponymous Vilnia (also Vilnelė) into the Neris. Probably settled as early as the Stone Age, the first written record dates back to 1323; Vilnius received Magdeburg city rights in 1387. From 1569 to 1795 Vilnius was the capital of the Lithuanian Grand Duchy in the Polish-Lithuanian noble republic. It lost this function in the Russian Tsarist Empire with the third partition of Poland-Lithuania. It was not until the establishment of the First Lithuanian Republic in 1918 that Vilnius briefly became the capital again. Between 1922 and 1940 Vilnius belonged to the Republic of Poland, so Kaunas became the capital of Lithuania. After the Second World War, Vilnius was the capital of the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic until Lithuania regained its independence in 1990.

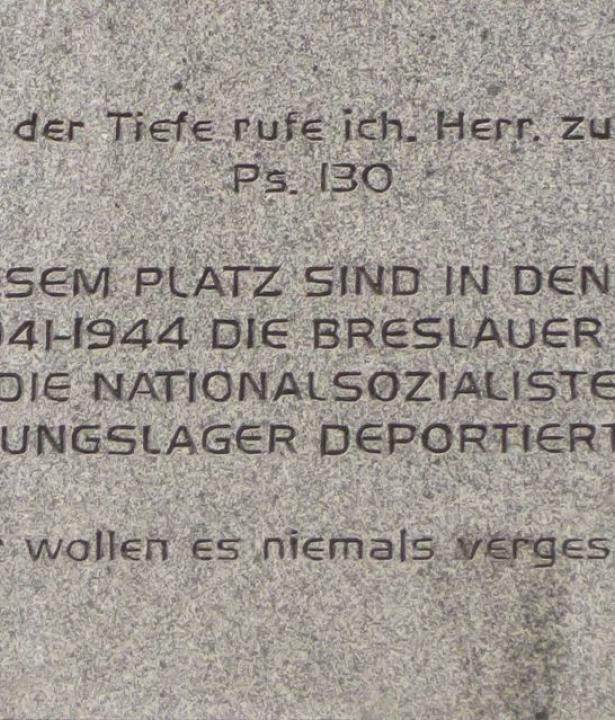

Already in the Middle Ages Vilnius was considered a center of tolerance. Jews in particular found refuge from persecution in Vilnius, so that Vilnius soon made a name for itself as the "Jerusalem of the North". Not least with the Goan of Vilnius, Elijah Ben Salomon Salman (1720-1797), Vilnius was one of the most important centers of Jewish education and culture. By the turn of the century, the largest population group was Jewish, while according to the first census in the Russian Tsarist Empire in 1897, only 2% belonged to the Lithuanian population group. From the 16th century onwards, numerous Baroque churches were built, which also earned the city the nickname "Rome of the East" and which still characterize the cityscape today, while the city's numerous synagogues were destroyed during the Second World War. Between 1941 and 1944 the city was under the so-called Reichskommissariat Ostland. During this period almost the entire Jewish population was murdered, only a few managed to escape.

Even today, the city bears witness to a "fantastic fusion of languages, religions and national traditions" (Tomas Venclova) and maintains its multicultural past and present.

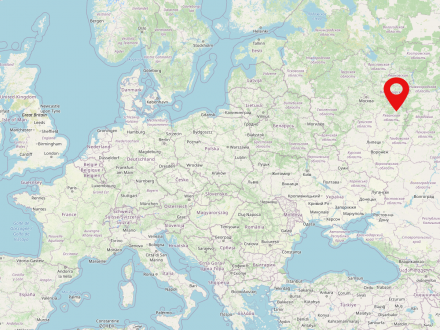

The Soviet Union (SU or USSR, Russian: Союз Советских Социалистических Республик (СССР) was a state in Eastern Europe, Central and Northern Asia existing from 1922 to 1991. The USSR was inhabited by about 290 million people and formed the largest territorial state in the world, with about 22.5 million square km. The Soviet Union was a socialist soviet republic with a one-party system.

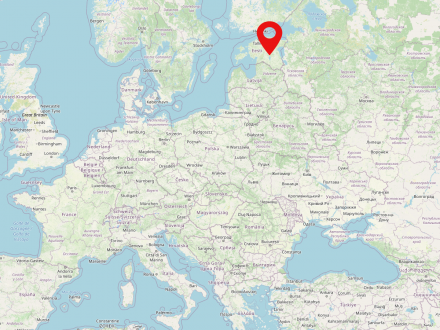

Saint Petersburg is a metropolis in the northeast of Russia. The city is home to 5.3 million people, which makes it the second largest in the country after Moscow. It is located at the mouth of the Neva River into the Baltic Sea in the Northwest Federal District of Russia. Saint Petersburg was founded by Peter the Great in 1703 and was the capital of Russia from 1712 to 1918. From 1914-1924 the city bore the name Petrograd, from 1924-1991 the name Leningrad.

I was [...], together with a group of twenty other Jews, captured on June 24. We were led to the town hall square, with our captors laughing and threatening to kill these 'damned Jews.' At the same time, the partisans began persecuting the Orthodox Jews who lived in the suburb of Vilijampole [...]. They started with sadistic games: they captured the Jews, forced them to dance, recite Hebrew prayers and sing the Socialist International. When they were tired of the games, they ordered the Jews to kneel down and shot them from behind. But that was only the beginning.

Aba Gefen: Ein Funken Hoffnung. Ein Holocaust-Tagebuch, S. 25

Kaunas is a town in Lithuania, about 100 km west of the capital Vilnius, and with nearly 304,000 inhabitants the second largest town in the country. From 1920 to 1940, Kaunas was itself the capital of Lithuania. Before 1918 - the founding year of the Lithuanian Republic - Kaunas was part of the Russian Empire, and for a long time before 1795 it belonged almost permanently to Poland-Lithuania.

You don't have to be afraid of the Germans. I remember them from the First World War – they are a highly civilized and cultural people.

I ran downstairs and found my family already gathered around the radio [...]. At breakfast father held a family meeting. We all felt that it would be too dangerous to stay in Kaunas. As frightening as the thought of the Russian police was, that of the Nazis was even more so [...]. Even if we ended up in Siberia, it would certainly be better than falling into the hands of the Nazis.

Solly Ganor: Das andere Leben. Kindheit im Holocaust, S. 37

Many memoirs describe family conversations similar to this one. In the small Jewish community in Estonia, there were discussions about the food situation in the Soviet Union being far worse than in the Estonian Soviet Socialist Republic. Orthodox Jews joined the fateful decision of the chief rabbi in

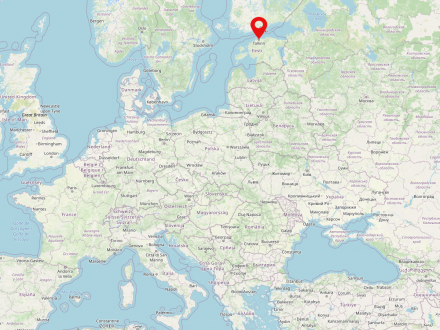

Tallinn (until 1918 Reval) is the capital of Estonia. It is located in the Harju County, right on the Baltic Sea and is home to about 434,000 people.

I've no more strength to take up the walking stick once again and set off on foot [...] I've taken off my heavy shoes, unpacked the backpack. I'm staying! [...] This is my final decision: I will rely on God's counsel, I'm staying. And at the same time I have made the final decision...to take up my pen... The Germans will make the city fascist. The Jews will have to go to the ghetto – and I will write all this down. My chronicle must see, must hear and become the mirror and the conscience of this great catastrophe and these difficult times.

Hermann Kruk: The Last Days of the Jerusalem of Lithuanian

After a few hours, the Zinghaus parents returned. They had boarded a crowded train together. More and more new people had crowded in. Then they, the old people, were overcome by such fear of this journey into the unknown that they parted from their children [...] and got off again. There they sat with us again. The old gentleman, already seventy years old and frail, with thick bristly white hair, crying like a child, and his wife was so worried about him and also crying, and we comforted her.

Helene Holzmann: "Dies Kind soll leben", S. 13

Poland is a state in Central Eastern Europe and is home to approximately 38 million people. The country is the sixth largest member state of the European Union. The capital and biggest city of Poland is Warsaw. Poland is made up of 16 voivodships. The largest river in the country is the Vistula (Polish: Wisła).

Pomerania is a region in northeastern Germany (Vorpommern) and northwestern Poland (Hinterpommern/Pomorze Tylne). The name is derived from the West Slavic 'by the sea' - 'po more/morze'. After the Thirty Years' War (Peace of Westphalia in 1648), Western Pomerania initially became Swedish, and Western Pomerania fell to Brandenburg, which was able to acquire further parts of Western Pomerania in 1720. It was not until 1815 that the entire region belonged to the Kingdom of Prussia as the Province of Pomerania. The province existed until the end of World War II, its capital was Szczecin (today Polish: Stettin).