The Soviet Union (SU or USSR, Russian: Союз Советских Социалистических Республик (СССР) was a state in Eastern Europe, Central and Northern Asia existing from 1922 to 1991. The USSR was inhabited by about 290 million people and formed the largest territorial state in the world, with about 22.5 million square km. The Soviet Union was a socialist soviet republic with a one-party system.

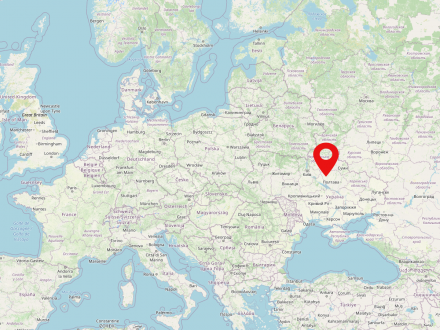

Ukraine is a country in eastern Europe inhabited by about 42 million people. Kiev is the capital and also the greatest city of Ukraine. The country has been independent since 1991. The Dnieper River is the longest river in Ukraine.

Belarus is a state in eastern Europe inhabited by about 9.5 million people. The capital and most populous city of the country is Minsk. After the disintegration of the Soviet Union in 1991, the state is independent. Belarus borders Ukraine, Poland, Lithuania, Latvia and Russia.

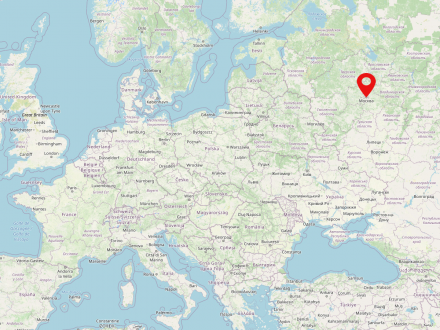

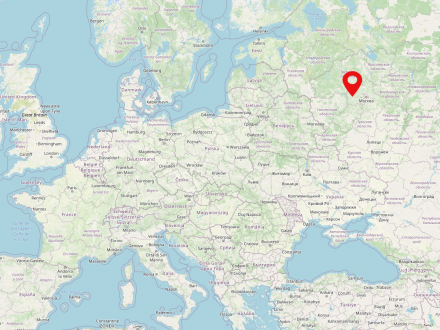

Moscow (Russian Москва́) is the capital of Russia and also the largest city in the country. With about 12.5 million inhabitants, Moscow is the largest city on the European continent.

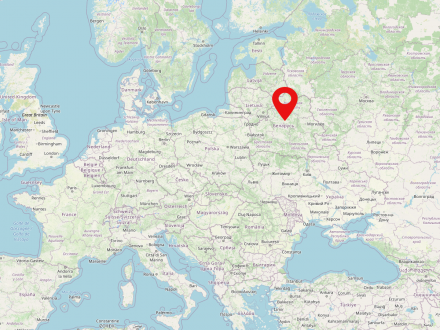

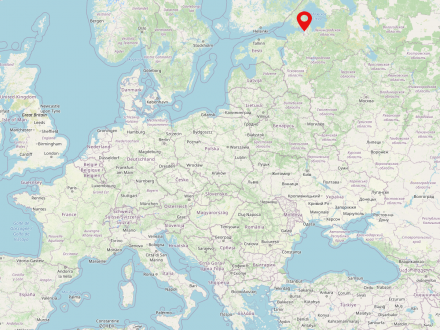

Saint Petersburg is a metropolis in the northeast of Russia. The city is home to 5.3 million people, which makes it the second largest in the country after Moscow. It is located at the mouth of the Neva River into the Baltic Sea in the Northwest Federal District of Russia. Saint Petersburg was founded by Peter the Great in 1703 and was the capital of Russia from 1712 to 1918. From 1914-1924 the city bore the name Petrograd, from 1924-1991 the name Leningrad.

We realized back then [1967] that we lived in an alien country, even if our Russian democratically-oriented friends were similarly outraged. The same happened the next year, when Soviet tanks crushed the Prague Spring. […] And we said to our friends: ‘This is your motherland, you have to fight for democracy; for us, Jews, there is nothing to do here.’ It seemed that we could not breathe the Soviet air anymore.1

Georgia is a republic in the South Caucasus. The land is inhabited by 3.7 million people and is located on the border between eastern Europe and western Asia. The capital of Georgia is Tbilisi. The country is located on the eastern end of the Black Sea and borders Russia as well as Turkey, Azerbaijan and Armenia. Georgia has been an independent state since the fall of the Soviet Union.

Today, Minsk is the capital of the Republic of Belarus. Its history dates back to 1067.

Over the centuries, Minsk belonged to the Principality of Polock, the Grand Duchies of Kiev and Lithuania, the united Poland-Lithuania, the Russian Empire, the Belarusian Democratic Republic (briefly the Lithuanian-Belarusian SSR), the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic, which belonged to the Soviet Union, and finally to Belarus. The multicultural city, which at all times was home to other minorities in addition to Jews, Poles, Russians and Belarusians, suffered repeatedly from passing armies and the consequences of war, for example in the Russo-Polish War (1654-1667), the Great Northern War (1700-1721), under Napoleon, and in the First and Second World Wars. Under German occupation, the largest ghetto in the occupied People's Republic was established in Minsk in 1941. The death camp Maly Trostinez was located near the city. At the same time, the surrounding forests were a center of resistance. After World War Two, the city was rebuilt in the socialist style, including housing for a population that was rapidly increasing due to industrialization and urbanization.

Vienna is the federal capital and the political, cultural and economic center of Austria. Around 1.9 million people live in the city alone, which is one-fifth of the country's population, and as many as one-third of all Austrians live in the metropolitan area. Historically, Vienna is particularly important as the capital and by far the most important residential city of the former Habsburg monarchy.

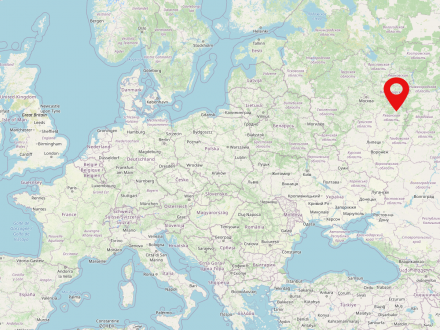

The Russian Federation is the largest territorial state in the world and is inhabited by about 145 million people. The capital and largest city is Moscow, with about 11.5 million inhabitants, followed by St. Petersburg with more than 5.3 million inhabitants. The majority of the population lives in the European part of Russia, which is much more densely populated than the Asian part.

Since 1992, the Russian Federation has been the successor state to the Russian Soviet Republic (Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic, RSFSR), by far the largest constituent state of the former Soviet Union. It is also the legal successor of the Soviet Union in the sense of international law.