"We lived in a herd." Dorota, a banker in

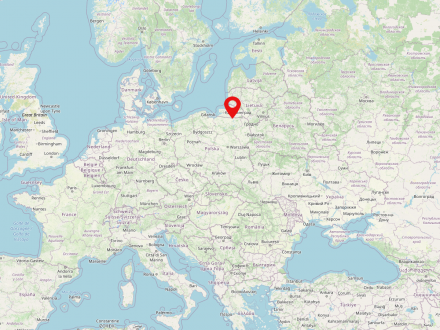

Giżycko is a town in the Polish voivodeship Warmia-Masuria. It was first mentioned in documents in 1340 as "Letzenburg" and "Lezcen". Giżycko is situated on an isthmus between the Jezioro Niegocin and the Jezioro Kisajno, a basin of the Jezioro Mamry.

In 2016 Giżycko had 29,642 inhabitants.

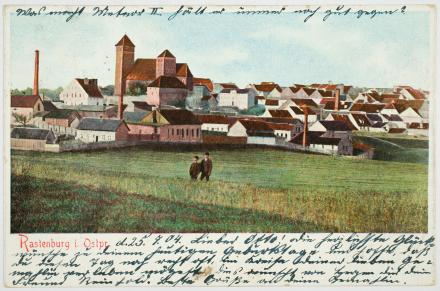

The picture shows a city view of Giżycko /Lötzen on a postcard from before 1945.

Agata Kern (born 1967) studied law, first in

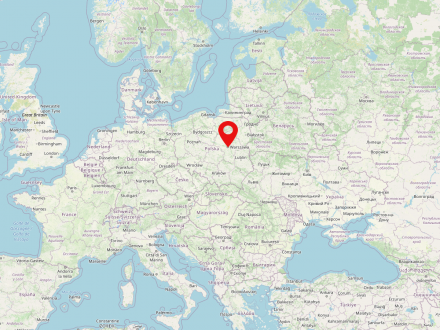

Warsaw is the capital of Poland and also the largest city in the country (population in 2022: 1,861,975). It is located in the Mazovian Voivodeship on Poland's longest river, the Vistula. Warsaw first became the capital of the Polish-Lithuanian noble republic at the end of the 16th century, replacing Krakow, which had previously been the Polish capital. During the partitions of Poland-Lithuania, Warsaw was occupied several times and finally became part of the Prussian province of South Prussia for eleven years. From 1807 to 1815 the city was the capital of the Duchy of Warsaw, a short-lived Napoleonic satellite state; in the annexation of the Kingdom of Poland under Russian suzerainty (the so-called Congress Poland). It was not until the establishment of the Second Polish Republic after the end of World War I that Warsaw was again the capital of an independent Polish state.

At the beginning of World War II, Warsaw was conquered and occupied by the Wehrmacht only after intense fighting and a siege lasting several weeks. Even then, a five-digit number of inhabitants were killed and parts of the city, known not least for its numerous baroque palaces and parks, were already severely damaged. In the course of the subsequent oppression, persecution and murder of the Polish and Jewish population, by far the largest Jewish ghetto under German occupation was established in the form of the Warsaw Ghetto, which served as a collection camp for several hundred thousand people from the city, the surrounding area and even occupied foreign countries, and was also the starting point for deportation to labor and extermination camps.

As a result of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising from April 18, 1943 and its suppression in early May 1943, the ghetto area was systematically destroyed and its last inhabitants deported and murdered. This was followed in the summer of 1944 by the Warsaw Uprising against the German occupation, which lasted two months and resulted in the deaths of almost two hundred thousand Poles, and after its suppression the rest of Warsaw was also systematically destroyed by German units.

In the post-war period, many historic buildings and downtown areas, including the Warsaw Royal Castle and the Old Town, were rebuilt - a process that continues to this day.

Jolanta Gernat (born 1967), a trained clothing technician, moved to Gütersloh with her husband, a German from Masuria, in 1994. Today she works in the housekeeping department of a retirement home.

However, no history lesson, no matter how gloomy, was able to cloud her childhood idyll. For many decades, her memories remained untouched: wooden toys and crayons, crafts with chestnuts, singing and dancing, songs like "Pieski małe dwa chciały przejść przez rzeczkę" ("Two little dogs want to cross a river"). One imagines a little doctor's office and a hairdresser's salon in miniature, and not to forget Marianna, the most loved of the kindergarten teachers. "When I think about it in retrospect, we were in the middle of nowhere," Agata marvels, "yet so much was happening!"

She never slept. She daydreamed, made up stories, and felt safe in the high-ceilinged hall, among the other children.

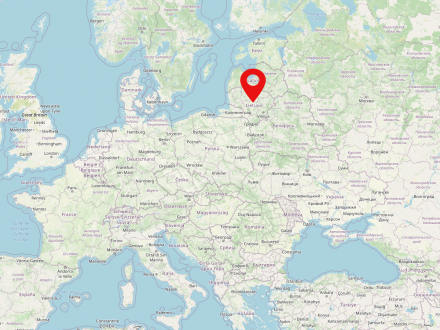

Vilnius is the capital and most populous city of Lithuania. It is located in the southeastern part of the country at the mouth of the eponymous Vilnia (also Vilnelė) into the Neris. Probably settled as early as the Stone Age, the first written record dates back to 1323; Vilnius received Magdeburg city rights in 1387. From 1569 to 1795 Vilnius was the capital of the Lithuanian Grand Duchy in the Polish-Lithuanian noble republic. It lost this function in the Russian Tsarist Empire with the third partition of Poland-Lithuania. It was not until the establishment of the First Lithuanian Republic in 1918 that Vilnius briefly became the capital again. Between 1922 and 1940 Vilnius belonged to the Republic of Poland, so Kaunas became the capital of Lithuania. After the Second World War, Vilnius was the capital of the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic until Lithuania regained its independence in 1990.

Already in the Middle Ages Vilnius was considered a center of tolerance. Jews in particular found refuge from persecution in Vilnius, so that Vilnius soon made a name for itself as the "Jerusalem of the North". Not least with the Goan of Vilnius, Elijah Ben Salomon Salman (1720-1797), Vilnius was one of the most important centers of Jewish education and culture. By the turn of the century, the largest population group was Jewish, while according to the first census in the Russian Tsarist Empire in 1897, only 2% belonged to the Lithuanian population group. From the 16th century onwards, numerous Baroque churches were built, which also earned the city the nickname "Rome of the East" and which still characterize the cityscape today, while the city's numerous synagogues were destroyed during the Second World War. Between 1941 and 1944 the city was under the so-called Reichskommissariat Ostland. During this period almost the entire Jewish population was murdered, only a few managed to escape.

Even today, the city bears witness to a "fantastic fusion of languages, religions and national traditions" (Tomas Venclova) and maintains its multicultural past and present.

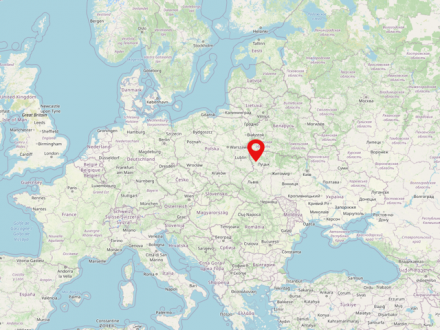

The historical landscape of Volhynia is located in northwestern Ukraine on the border with Poland and Belarus. Already in the late Middle Ages the region fell to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and from 1569 on belonged to the united Polish-Lithuanian noble republic for more than two centuries. After the partitions of Poland-Lithuania at the end of the 18th century, the region came under the Russian Empire and became the name of the Volhynia Governorate, which lasted until the early 20th century. The Russian period also saw the immigration of German-speaking population (the so-called Volhyniendeutsche), which peaked in the second half of the 19th century. After the First World War Volhynia was divided between Poland and the Ukrainian Soviet Republic, from 1939, as a result of the Hitler-Stalin Pact, completely Soviet and already in 1941 occupied by the Wehrmacht. Under German occupation there was systematic persecution and murder of the Jewish population as well as other parts of the population.

After World War II, Volhynia again belonged to the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic and since 1992 to Ukraine. The landscape gives its name to the present-day Ukrainian oblast with its capital Luzk (ukr. Луцьк), which is not exactly congruent.

Outer Subcarpathia is the name given to the area on the outer side of the Carpathian Arc. The Polish voivodeship Podkarpackie takes its name from this.

The village of Sztynort is located in the north of the Masurian Lake District on the Jez Peninsula between Jezioro Mamry, Jezioro Dargin and Jezioro Dobskie. Until 1928 the village was called Groß Steinort, then Steinort.

"Who are you? - A little Pole! - What is your sign? - The eagle!" they had learned in kindergarten. They knew exactly who Poland's enemies were: The Teutonic Order in the Crusader movie based on Henryk Sienkiewicz, which they had seen at the Pałac Cinema. And the Nazis from the TV series "Four Tank Soldiers and a Dog", scenes from which they would reenact in the Pałac park.

Her generation had an intimate relationship with nature, the landscape, water, sky. It was only a short walk to Steinort Lake. Fishing, bathing, boating, "that was wonderful." Masuria was home for her. Unlike for her grandparents, who were survivors, dumped somewhere in a foreign land. Unlike for her parents, who grew up in the poor, sorrowful post-war years, only slowly putting down roots.

"I was often afraid." Later she wondered where that came from. "Nothing terrible had happened directly to me." It had to do with the family history, and the silence around it. Only Agata's grandfather Waldemar spoke about it now and then. "We came from Vilnius…there was nothing more beautiful." He was a man who lived in his own world of roses and bees and books. "The most terrible word in the Polish language is repatriacja" – Agata still has this phrase in her ear. For her grandparents coming to Sztynort was no homecoming. Their “patria” was and would forever remain

Lithuania is a Baltic state in northeastern Europe and is home to approximately 2.8 million people. Vilnius is the capital and most populous city of Lithuania. The country borders the Baltic Sea, Poland, Belarus, Russia and Latvia. Lithuania only gained independence in 1918, which the country reclaimed in 1990 after several decades of incorporation into the Soviet Union.

A last memory of Vilnius, just before the forced resettlement began, was their wedding in May 1945 in the chapel of the famous Ostra Brama, the Gate of Dawn.

Węgorzewo is a city in northeastern Poland in Warmińsko-Mazurskie Voivodeship. It is inhabit by about 11,000 people and is located not far from the border of Poland with Russia.

Zweiten Weltkrieges zunächst den Namen Dryfort erhalten hatte, wurde 1950 nach Stanisław Srokowski (1872-1950) umbenannt, dem Leiter des „Polnischen Komitees zur Festsetzung von Ortsnamen“ in den sog. „Wiedergewonnenen Gebieten“.

Jolanta married her childhood sweetheart Jacek Gernat in August 1989. The young couple already had their eyes set on Germany, relatives who lived there were trying to convince them to move, and the economic crisis in Poland did the rest – in 1994 the time had come. Jolanta left her large family behind in Masuria. For many years, Gütersloh was for her a valley of tears.

Iwona and Dorota struggled to find their way at home; information technology and finance were promising industries. The upswing in the province where structures were weak was a long time coming, but it finally came, along with family, house and garden. Plus the lakes and forests that had always been there.

The connections from the kindergarten days have never been completely severed. Thanks to Facebook, they are now becoming livelier, with Dorota communicating most eagerly. She dreams of them all meeting up one day in Sztynort.

The four women recently shared their thoughts about the future of the castle. Should it be a museum for the history of Masuria or rather for art and culture? An educational center for young people? It would also be important to remember the socialist years, which are of little value today. For example, the biographies of the girls and boys from the kindergarten could be told.