What motivated him to devote all his energy to Lehndorff Palace? The technical challenge? The responsibility of his generation to keep alive the memory of the resistance against Hitler? The trigger was Antje Vollmer's book "Doppelleben" about the fate of Heinrich and Gottliebe Lehndorff.

From the outside, the manor house in the former village of

The village of Sztynort is located in the north of the Masurian Lake District on the Jez Peninsula between Jezioro Mamry, Jezioro Dargin and Jezioro Dobskie. Until 1928 the village was called Groß Steinort, then Steinort.

But then the money dried up, and there was no longer-term perspective for the huge project. Nevertheless, engineer Wolfram Jäger jumped in without hesitation. "Making the impossible possible!" An important motto in his life.

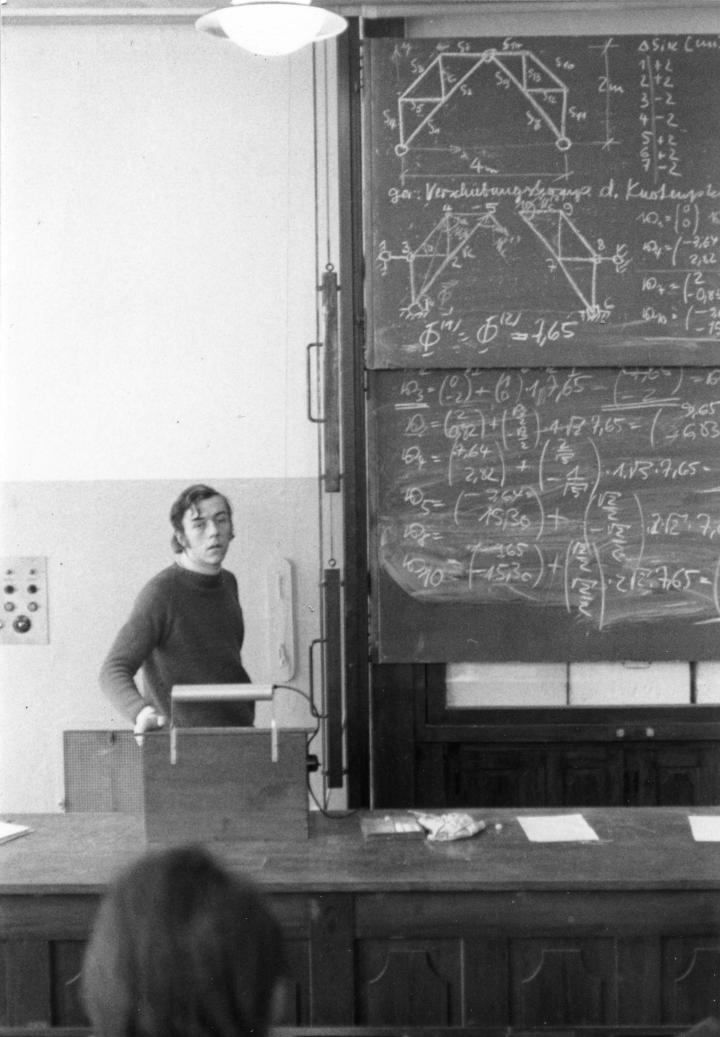

Nevertheless, Wolfram Jäger decided to continue the family tradition: He did an apprenticeship as a bricklayer, studied civil engineering in Dresden, and gained a doctorate in construction mechanics in 1977. In 1980, he attended construction college in

Moscow (Russian Москва́) is the capital of Russia and also the largest city in the country. With about 12.5 million inhabitants, Moscow is the largest city on the European continent.

In the GDR, going one's own way or embarking on a university career was not possible even for a top student. He was not a member of the SED, did not want to join a combine or work to make up shortages in the construction industry. So he looked for niches, changed jobs several times and finally found a job that suited him in the GDR's construction academy before the fall of the Wall.

The work picked up quickly and so did his self-confidence. A proposal for the archaeological demolition of the ruins of the Frauenkirche in Dresden won him a position on the project in 1992. Even in GDR times, he had dreamed of its reconstruction and hatched ideas. How could a masonry structure like that be rebuilt using old techniques, while meeting today's requirements? Innovative solutions were needed to stay as close as possible to the original.

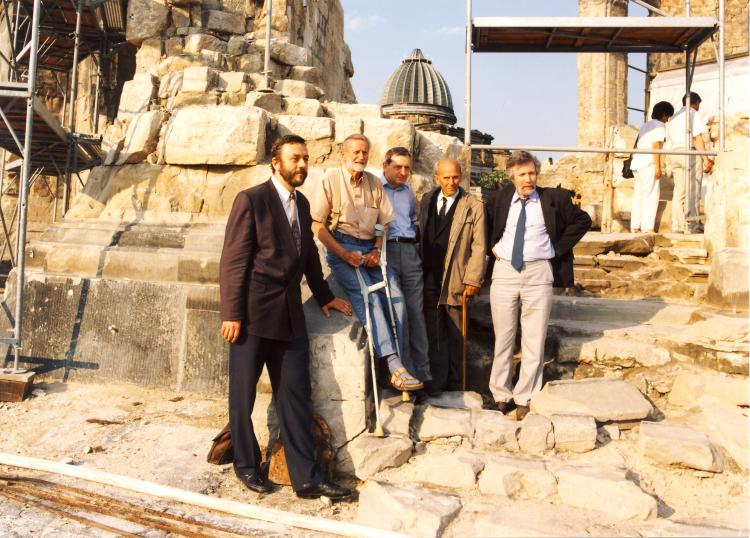

He was attracted by unusual challenges. In Syria, he renovated the knight's tower of the world-famous crusader castle Krak des Chevaliers near Homs. In Iran, he and his team rebuilt the Sistani House – part of the important citadel of Bam, which was destroyed by an earthquake in 2003. In the process, he introduced methods for earthquake-resistant reconstruction of earthen buildings.

It was a race against time and progress was constantly hampered by a lack of funding. After approaching them repeatedly, the German Federal Environmental Foundation donated €125,000. In order to receive the funding, however, Wolfram Jäger had to prove that the damage to the palace had been caused as a result of human-made climate change.

Jäger made contact with the local contractor Matthias Hohl, who is originally from Switzerland but has been living in Masuria for some time, and has experience in tunnel construction. Just the right man for the dangerous work in the half-collapsed cellars.

In ten years, Wolfram Jäger's passion has not been extinguished. But you can sense his impatience. He has never managed such a chronically underfinanced building project. More money is urgently needed, as well as a lobby group.

The other Steinort enthusiasts – ethnologists, historians, artists, teachers – also need staying power and money to bring the castle back to life. The cultural "trades" manage with much less.

Many heads came together and there were a lot of different ideas. The engineer at the helm of the huge construction site set the pace. Together with his students, he developed a utilization concept – based on various ideas that were circulating – that found favor with the Federal Commissioner for Culture and the Media. Since 2019, half a million euros from the federal budget has been flowing into Steinort every year.

It's a drop in the bucket compared to the tens of millions still needed for construction. Nevertheless, a breakthrough – Steinort finally has a place on the German political agenda.

The city of Olsztyn (population 2022: 168,212) was founded in 1353 as Allensteyn on the Łyna river. Olsztyn is the largest city in Warmia and the capital of the Warmian–Masurian Voivodeship. The city is member of the European Route of Brick Gothic, especially because of its Old Town market sqare and the Castle of Warmian Cathedral Chapter.

The picture shows a city view of Olsztyn /Allenstein on a postcard from before 1945.

One of the projects that has been particularly close to their hearts is the restoration of the Lehndorff family’s funeral chapel (https://www.jaeger-ingenieure.de/de/news-reader/erbbegraebniskapelle-der-fam-lehndorff-in-sztynort-polen.html), designed by the famous Berlin architect Friedrich August Stüler. But for a long time, no one took responsibility. In 2015, Wolfram Jäger had wandered through the overgrown cemetery for the first time; the sight of the ruined chapel had shocked him. Birch trees were growing out of the roof, and the vaulted ceiling was on the verge of collapse. The restoration became a tour de force for the engineer and everyone involved.

"It was an unforgettable time" – of disasters but also real elation. "For twelve days," Wolfram Jäger recounts, "I worked on my own at dizzying heights." At one critical moment, a bricklayer was needed but they couldn’t find one locally, so he drove from Radebeul to Sztynort and got started on the job himself. "After all, I had learned bricklaying as a young man." There was hardly any technical equipment on hand, he had to fetch water from the lake. "The sun shone down through the trees. I would close my eyes, breathe out, pause for a moment, then continue building. It was just dreamlike."

It will take ten more years – that’s the best-case scenario. From the engineer's point of view, it’s a feasible achievement, provided the money is there. By then he would be eighty. Basking in success, as he did with the Frauenkirche! Next summer, tourists will be invited to visit the palace as a "living construction site" to watch the work being done and make donations. As each room is completed, it will be used immediately...