Giżycko is a town in the Polish voivodeship Warmia-Masuria. It was first mentioned in documents in 1340 as "Letzenburg" and "Lezcen". Giżycko is situated on an isthmus between the Jezioro Niegocin and the Jezioro Kisajno, a basin of the Jezioro Mamry.

In 2016 Giżycko had 29,642 inhabitants.

The picture shows a city view of Giżycko /Lötzen on a postcard from before 1945.

Wydminy is a village in Poland located 18 kilometers southeast of Giżycko (Lötzen) on the Jezioro Wydmińskie. The first written mention of Widminnen dates back to 1480.

2,300 people lived in Wydminy in 2012.

The picture shows a postcard of the Wydminy

/Widminnen waterfront before 1945.

What is Masuria? What was it before 1945? Many people now began asking themselves these questions. Monuments from German times were restored and maintained. Marek together with his older brother and their parents cleaned up a commemorative boulder, dedicated to the memory of Friedrich Dewischeit, the German poet and author of the Masurian song: "Wild flutet der See, drauf schaukelt den Fischer der schwankenden Kahn".

Stories that had been suppressed for a long time came to light. An old lady in Marek's house told how the Russians burned the palace’s library in 1945. At the sailing camps, people talked about how the palace used to look. Facts mixed with rumors – so vivid and colorful, "I felt like I’d actually been there.”

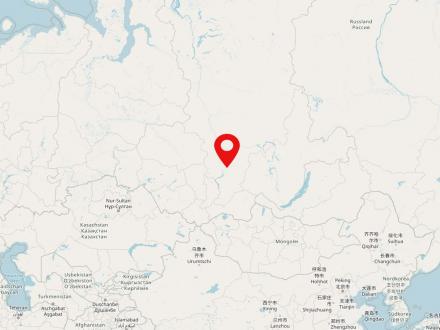

Siberia covers an area of 12.8 million square kilometers between the Urals, the Pacific Ocean, the North Polar Sea, China and Mongolia.The Russian conquest of Siberia began in 1581/82. At the time of the Enlightenment mainly a source of raw materials and space for trade with Asia, Siberia gained importance from the 19th century as a place for penal colonies and exiles. With the development of the Trans-Siberian Railway and steam navigation at the end of the 19th century, industrialization and thus new settlers came to Siberia. Further industrialization under Stalin was implemented primarily with the labor of Gulag prisoners and prisoners of war.

The map shows North Asia, centrally located Siberia. CIA World Factbook, edited by Veliath (2006) and Ulamm (2008). CC0 1.0.

Krasnoyarsk is today the third largest city in Siberia. Founded in 1628 as a military outpost, from 1895 onwards the city benefited in its development from the connection with the Trans-Siberian Railway. During World War II, the Krasnoyarsk region was a destination for both evacuaees from the war zone in the west and exiles for forced labor.

At thirteen or fourteen, Piotr and Marek fell in love with jazz. And because the jazz club was in the same building as the Masurian Society, one thing led to another. That's where their paths crossed. People in Giżycko who were interested in music and history "just had to get to know each other."

The city of Olsztyn (population 2022: 168,212) was founded in 1353 as Allensteyn on the Łyna river. Olsztyn is the largest city in Warmia and the capital of the Warmian–Masurian Voivodeship. The city is member of the European Route of Brick Gothic, especially because of its Old Town market sqare and the Castle of Warmian Cathedral Chapter.

The picture shows a city view of Olsztyn /Allenstein on a postcard from before 1945.

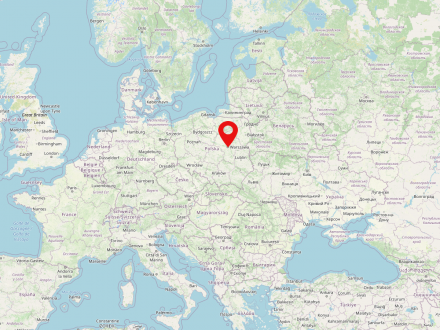

Warsaw is the capital of Poland and also the largest city in the country (population in 2022: 1,861,975). It is located in the Mazovian Voivodeship on Poland's longest river, the Vistula. Warsaw first became the capital of the Polish-Lithuanian noble republic at the end of the 16th century, replacing Krakow, which had previously been the Polish capital. During the partitions of Poland-Lithuania, Warsaw was occupied several times and finally became part of the Prussian province of South Prussia for eleven years. From 1807 to 1815 the city was the capital of the Duchy of Warsaw, a short-lived Napoleonic satellite state; in the annexation of the Kingdom of Poland under Russian suzerainty (the so-called Congress Poland). It was not until the establishment of the Second Polish Republic after the end of World War I that Warsaw was again the capital of an independent Polish state.

At the beginning of World War II, Warsaw was conquered and occupied by the Wehrmacht only after intense fighting and a siege lasting several weeks. Even then, a five-digit number of inhabitants were killed and parts of the city, known not least for its numerous baroque palaces and parks, were already severely damaged. In the course of the subsequent oppression, persecution and murder of the Polish and Jewish population, by far the largest Jewish ghetto under German occupation was established in the form of the Warsaw Ghetto, which served as a collection camp for several hundred thousand people from the city, the surrounding area and even occupied foreign countries, and was also the starting point for deportation to labor and extermination camps.

As a result of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising from April 18, 1943 and its suppression in early May 1943, the ghetto area was systematically destroyed and its last inhabitants deported and murdered. This was followed in the summer of 1944 by the Warsaw Uprising against the German occupation, which lasted two months and resulted in the deaths of almost two hundred thousand Poles, and after its suppression the rest of Warsaw was also systematically destroyed by German units.

In the post-war period, many historic buildings and downtown areas, including the Warsaw Royal Castle and the Old Town, were rebuilt - a process that continues to this day.

Wrocław (German: Breslau) is one of the largest cities in Poland (population in 2022: 674,079). It is located in the Lower Silesian Voivodeship in the southwest of the country.

Initially under Bohemian, Piast and at other times Hungarian rule, the Habsburgs took over the Silesian territories in 1526, including Wrocław. Another turning point in the city's history was the occupation of Wroclaw by Prussian troops in 1741 and the subsequent incorporation of a large part of Silesia into the Kingdom of Prussia.

The dramatic increase in population and the fast-growing industrialization led to the rapid urbanization of the suburbs and their incorporation, which was accompanied by the demolition of the city walls at the beginning of the 19th century. By 1840, Breslau had already grown into a large city with 100,000 inhabitants. At the end of the 19th century, the cityscape, which was often still influenced by the Middle Ages, changed into a large city in the Wilhelmine style. The highlight of the city's development before the First World War was the construction of the Exhibition Park as the new center of Wrocław's commercial future with the Centennial Hall from 1913, which has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 2006.

In the 1920s and 30s, 36 villages were incorporated and housing estates were built on the outskirts of the city. In order to meet the great housing shortage after the First World War, housing cooperatives were also commissioned to build housing estates.

Declared a fortress in 1944, Wrocław was almost completely destroyed during the subsequent fightings in the first half of 1945. Reconstruction of the now Polish city lasted until the 1960s.

Of the Jewish population of around 20,000, only 160 people found their way back to the city after the Second World War. Between 1945 and 1947, most of the city's remaining or returning - German - population was forced to emigrate and was replaced by people from the territory of the pre-war Polish state, including the territories lost to the Soviet Union.

After the political upheaval of 1989, Wrocław rose to new, impressive heights. The transformation process and its spatial consequences led to a rapid upswing in the city, supported by Poland's accession to the European Union in 2004. Today, Wrocław is one of the most prosperous cities in Poland.

In 2010, Piotr Wagner received a call in Warsaw from the Polish-German Foundation for the Preservation of Culture and Monuments. It had just bought the decaying Lehndorff Palace and urgently needed an interpreter. That appealed to him. Soon he belonged to the inner circle of idealists whose mission was to save and revive the castle. In his free time, he became acquainted with the locals, went shopping for old people, drove them to the doctor, and made new friends.

Located in Masuria, Puszcza Piska is the largest forest area in Poland, covering over 1,000 km². Until 1945, it was the largest forest in the German Empire.

The photo shows a clearing with a lake in Puszcza Piska /Johannisburger Heide before 1935.

Marek got talking with one sailor from Warsaw, a board member of the "King Cross Group," an Italian company that builds shopping centers in Eastern Europe, with a sensitivity for the local areas and important sites. "Italians care about culture and history." The sailors’ connection turned into a new beginning for Sztynort. In 2018, King Cross bought the marina and the land around the castle. They are cooperating closely with the Polish-German foundation, which is responsible for looking after the palace.

His friend Piotr Wagner will continue to work for the future of the castle. He will support the builders, the annual cultural festival (cross-reference to chapter Hannah Wadle), and the German-Polish Foundation's arduous struggle to raise public funds. Wherever possible, he will be involved in thinking and discussing ways to put this grand, rambling building to good use.

Vilnius is the capital and most populous city of Lithuania. It is located in the southeastern part of the country at the mouth of the eponymous Vilnia (also Vilnelė) into the Neris. Probably settled as early as the Stone Age, the first written record dates back to 1323; Vilnius received Magdeburg city rights in 1387. From 1569 to 1795 Vilnius was the capital of the Lithuanian Grand Duchy in the Polish-Lithuanian noble republic. It lost this function in the Russian Tsarist Empire with the third partition of Poland-Lithuania. It was not until the establishment of the First Lithuanian Republic in 1918 that Vilnius briefly became the capital again. Between 1922 and 1940 Vilnius belonged to the Republic of Poland, so Kaunas became the capital of Lithuania. After the Second World War, Vilnius was the capital of the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic until Lithuania regained its independence in 1990.

Already in the Middle Ages Vilnius was considered a center of tolerance. Jews in particular found refuge from persecution in Vilnius, so that Vilnius soon made a name for itself as the "Jerusalem of the North". Not least with the Goan of Vilnius, Elijah Ben Salomon Salman (1720-1797), Vilnius was one of the most important centers of Jewish education and culture. By the turn of the century, the largest population group was Jewish, while according to the first census in the Russian Tsarist Empire in 1897, only 2% belonged to the Lithuanian population group. From the 16th century onwards, numerous Baroque churches were built, which also earned the city the nickname "Rome of the East" and which still characterize the cityscape today, while the city's numerous synagogues were destroyed during the Second World War. Between 1941 and 1944 the city was under the so-called Reichskommissariat Ostland. During this period almost the entire Jewish population was murdered, only a few managed to escape.

Even today, the city bears witness to a "fantastic fusion of languages, religions and national traditions" (Tomas Venclova) and maintains its multicultural past and present.

Siberia covers an area of 12.8 million square kilometers between the Urals, the Pacific Ocean, the North Polar Sea, China and Mongolia.The Russian conquest of Siberia began in 1581/82. At the time of the Enlightenment mainly a source of raw materials and space for trade with Asia, Siberia gained importance from the 19th century as a place for penal colonies and exiles. With the development of the Trans-Siberian Railway and steam navigation at the end of the 19th century, industrialization and thus new settlers came to Siberia. Further industrialization under Stalin was implemented primarily with the labor of Gulag prisoners and prisoners of war.

The map shows North Asia, centrally located Siberia. CIA World Factbook, edited by Veliath (2006) and Ulamm (2008). CC0 1.0.

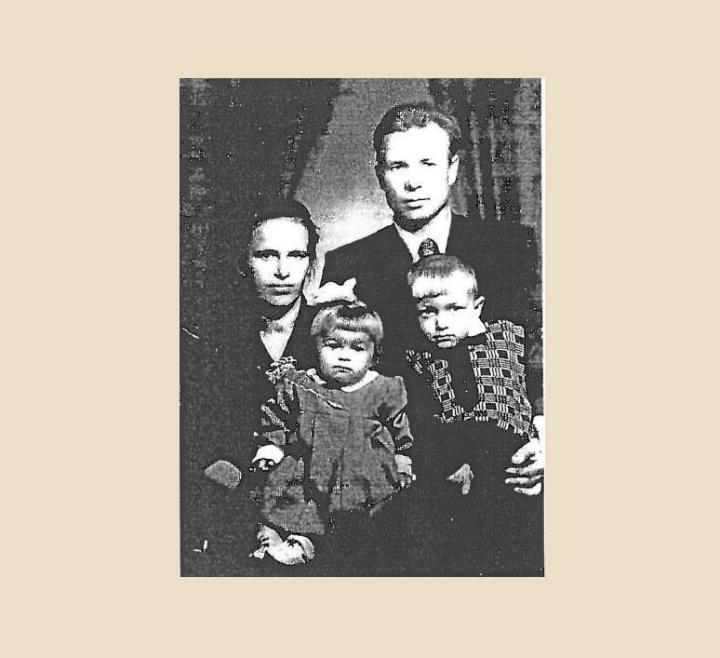

In 1957 they were released, but did not know where to go. When they crossed Masuria by train and saw an empty house, they got off – just outside of Giżycko.

A characteristic of Masuria, says Piotr Wagner, is that it’s a place where people want to come to rest. But after 1945, as well as earlier, in German times, "politics, unfortunately, usually got in the way."

This time, however, it could turn out well. Meanwhile, in the village of Sztynort, the mood is cautiously optimistic. Of the 70 registered residents, about 40 live here year-round; before 1989, there were more than twice that number. Many old houses have recently been renovated, and the owners are turning down offers from interested buyers from the city. Maybe their daughter or son will return soon?

At the end of the village street, new houses are being built in the traditional style, there’ll be thirty of them, the builder is King Cross. Moving into one of them would be quite an attractive prospect, thinks Marek Makowski. Piotr Wagner, who has been a father for five years, agrees. “Steinort has found me," he says.