Other cities quickly followed Vienna's example; around 1800, almost every major city in the Habsburg Empire had similar coffeehouses. This was also the case in

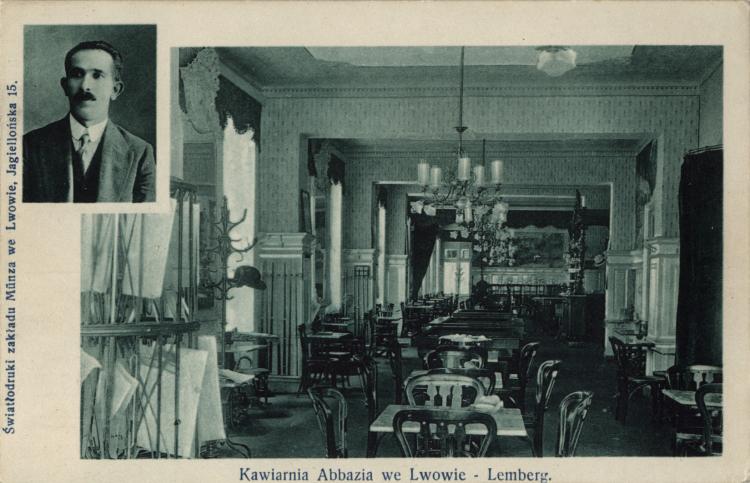

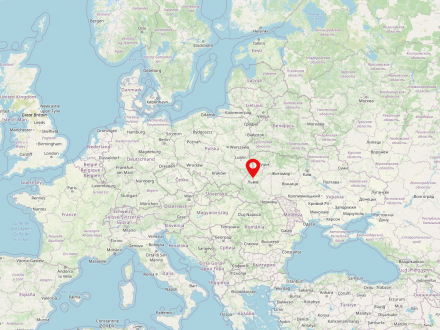

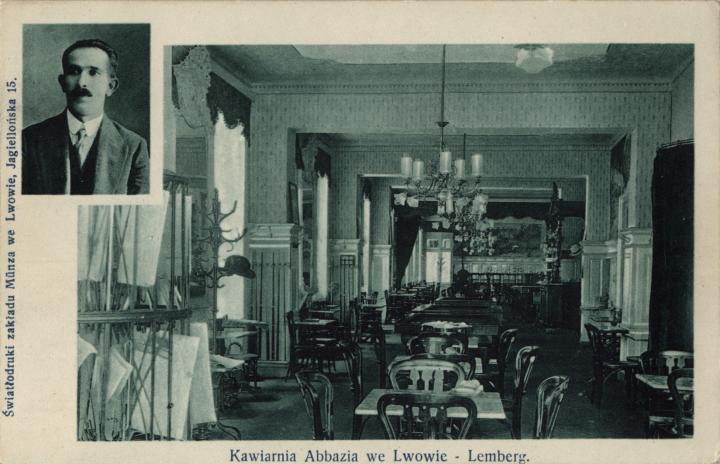

Lviv (German: Lemberg, Ukrainian: Львів, Polish: Lwów) is a city in western Ukraine in the oblast of the same name. With nearly 730,000 inhabitants (2015), Lviv is one of the largest cities in Ukraine. The city was part of Poland and Austria-Hungary for a long time.

Due to the war in Ukraine, it is possible that this information is no longer up to date.

The more exclusive coffeehouses attracted mainly artists and the upper class – workers could usually only afford the cheaper pubs where grain coffee was served. In general, coffeehouses adapted to their clientele: Cafés frequented mainly by families were open during the day, while those catering to artists were often open late into the night. For the latter, these were important places where they could escape from their usually rather shabby living quarters. The price of a coffee bought them an environment and atmosphere in which they could work in peace – and in which many important literary works were created.

“In order to grasp this, one must understand that the Viennese coffeehouse is an institution of a special kind, unlike any other in the world. It is, in fact, a kind of democratic club, accessible to everyone for the price of a cheap cup of coffee, where any guest, in return for this small obolus, can sit for hours, discuss, write, play cards, receive his mail and, above all, consume an unlimited number of newspapers and magazines.”3

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, mainly Polish artists met here. However, local organizations such as the Lemberg bicycle club and the Lemberg photography society used the premises for their meetings as well. The café was a hub for social actions too – donations for Polish emigrants from Prussia were collected here. The most important guests were also accommodated in other ways: Being a popular venue for Polish officers, who were not exactly fond of the German Reich, in 1901, the new owner Jakób Rollauer decided to cancel the café’s subscription to all Berlin newspapers.

Nevertheless, “the Schneider” was by no means the undisputed, sole meeting place of the Polish-language press. On the contrary, another Polish newspaper, the Goniec Polski (Polish Messenger), made every effort to portray the coffeehouse in as bad a light as possible. For its editors, the café was a place of drunkenness and immoral behavior, which can be seen reflected in the following description of its clientele: “Long-haired poets, bearded painters, gray-haired reviewers, all drinking as if there were no tomorrow.”5

“Franko would come here for coffee and newspapers. Besides him, [Mychailo] Hruševskyj, [Volodymyr] Hnatiuk, [Fedir] Vovk and other scientists with close ties to the Scientific Ševčenko Society would meet here. They had a separate table for themselves and could gather to enjoy a rest from work, read the latest news and have a good chat. And if you wanted to meet with one of them, you could find the person you were looking for here in the afternoon around five o'clock, without having to go to their office or home.”6

“There were beauties with deep-cut necklines, Jewish actresses who performed at the Yiddish Gimpel Theater, [...] students from the yeshiva with their long beards who came for a scientific discussion with Reb Gershom Bader, [...] and loafers, [...] whose mission it was to read newspapers all day until 3am.”7