The Russian Empire (also Russian Empire or Empire of Russia) was a state that existed from 1721 to 1917 in Eastern Europe, Central Asia and North America. The country was the largest contiguous empire in modern history in the mid-19th century. It was dissolved after the February Revolution in 1917. The state was regarded as autocratically ruled and was inhabited by about 181 million people.

“When you have measured out the right amount of melted aspic into a pan, add the raw egg yolks, Provencal oil, vinegar, mustard and salt. Then put the pan on ice and beat the sauce first with a metal whisk and then with a spatula until it turns white and is thick enough to stick to the side of a dish without running down. This sauce is mainly added to cold meat and fish dishes.”5

“In a deep bowl, beat the raw egg yolks, add the cooked mustard, knead a little and then pour the Provençal oil into the yolks in a thin stream, stirring quickly with a whisk. When the oil is used up and the sauce is thick enough to stick to a spatula without running down, add a pinch of tarragon or, if this is not available, some table vinegar, then stir once and add a pinch of salt and a pinch of sugar. The sauce à la provençale can be served with cold meats, poultry, game and fish, as well as with some fried dishes.”9

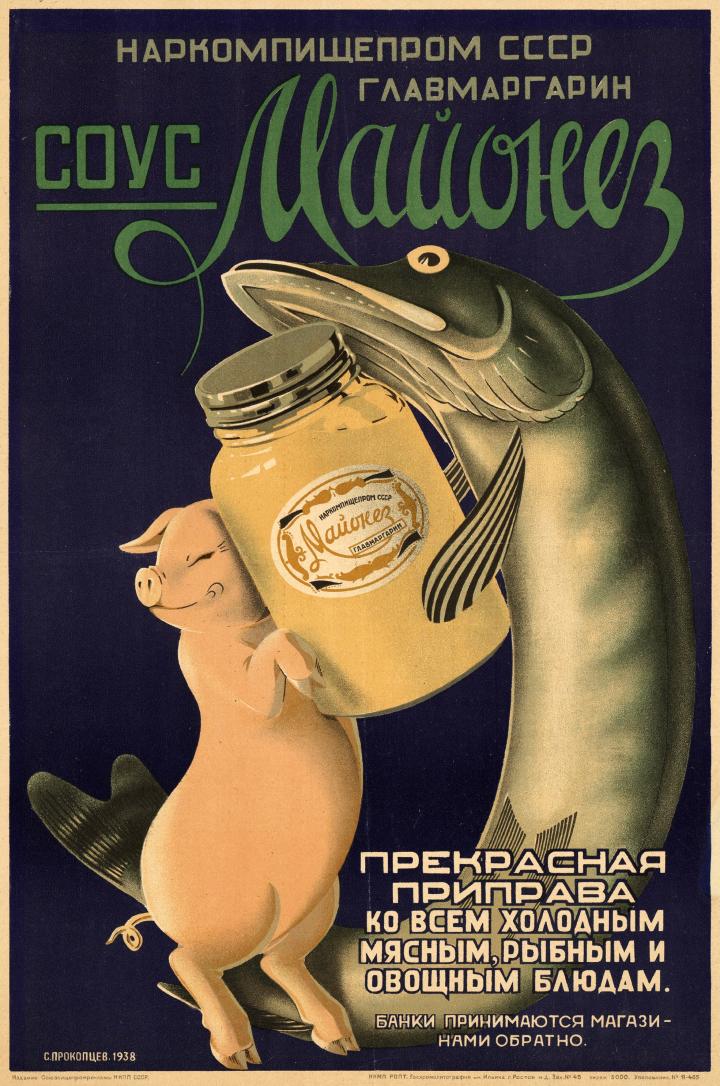

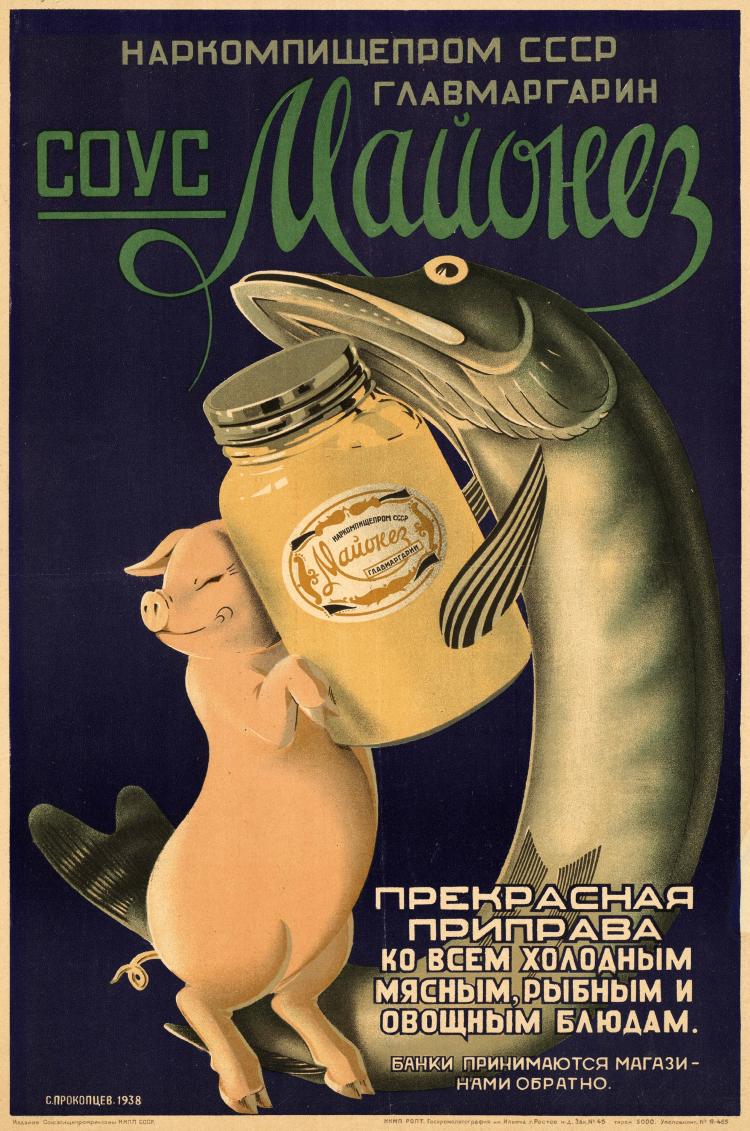

“To dress salads, vinaigrettes and other cold dishes, housewives usually use vegetable oil, vinegar, mustard, horseradish and other seasonings. All these condiments can be replaced with great success by mayonnaise sauce, [...] developed by the Institute of Nutrition at the USSR People's Commissariat of Health. Mayonnaise sauce has a high quality and degree of flavor that homemade condiments do not have. Mayonnaise sauce can be served with all cold dishes – meat, fish, and also as an accompaniment to vinaigrettes, potatoes, salads, herrings, etc. Take one to two tablespoons of mayonnaise per serving, depending on taste.”12

“The reason for this is that even slight changes in the quantity and quality of ingredients and insufficient care in the preparation of the sauce affect the taste and strength of the mixture (emulsion) and result in a sauce that either does not work at all or does not taste right.”13

The Soviet Union (SU or USSR, Russian: Союз Советских Социалистических Республик (СССР) was a state in Eastern Europe, Central and Northern Asia existing from 1922 to 1991. The USSR was inhabited by about 290 million people and formed the largest territorial state in the world, with about 22.5 million square km. The Soviet Union was a socialist soviet republic with a one-party system.

“Olive salad was rightly placed in the center of the table, which was decorated with a festive tablecloth. The overall composition was supported by a cooked Hungarian chicken (head removed, feet up), boiled potatoes, meat aspic (cooked the day before, poured into bowls and cooled on the balcony), fish aspic, “herring under the fur coat”, sausage cleanly cut with a specially sharpened knife, salted red and (or) white fish, balyk of pork, boiled eggs with red caviar, etc. [...]”17