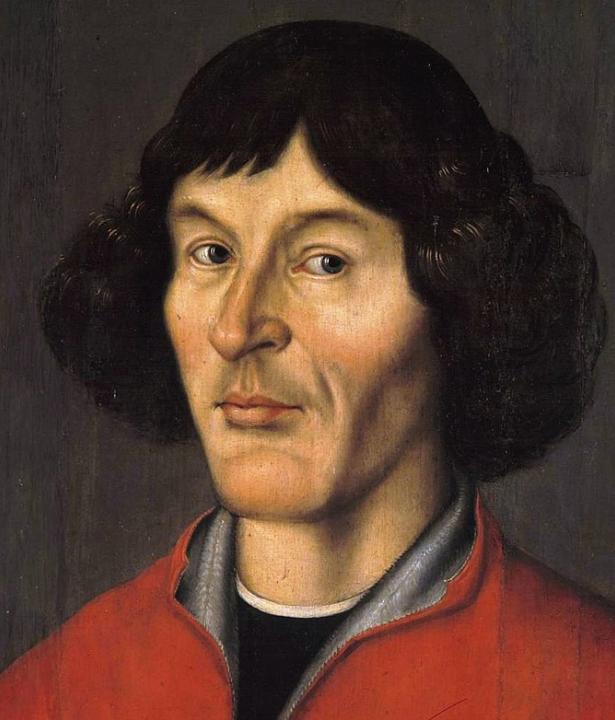

The 550th anniversary of Nicolaus Copernicus’ birth invites us to look at the mark that the astronomer left on the world. And it is also an opportunity to look more closely at how Copernicus has been viewed in the past and how these anniversaries have been treated differently in different periods of history.

Text

Few historical figures from the early modern period remain as visible today as Nicolaus Copernicus – in Poland, in Germany, and across the world. He achieved his intellectual breakthrough by proposing a new worldview – in which it was the Sun and not the Earth that stood at the center of the planetary system – several centuries before it was possible to prove the accuracy of heliocentrism through scientific experiments. This breakthrough has seen Copernicus and his ideas become a cultural legacy with which people have identified over more than three centuries, and in a broad range of contexts. For example, in 1873, to mark the 400th anniversary of Copernicus’ birth, Polish artist Jan Matejko painted the astronomer “in conversation with God.” One century later, to celebrate the 500th anniversary of his birth, the socialist states lauded Copernicus as the pioneer of an atheism rooted in science.

Text

This enormous wealth of references, attributions, and interpretations means that, even to this day, delving into the life and works of Copernicus is a truly fascinating and worthwhile pursuit. It opens up a world that goes far beyond that of astronomy and the natural sciences. According to cultural theorist Elisabeth Ritter, who studied the concept of Copernicus as a German-Polish “memorial site”, the scholar from a place that is now part of northern Poland has become a “strongly charged symbol [...] irrespective of knowledge of his actual work.”1 In terms of cultural history, the Renaissance scholar Copernicus can in some ways be compared to the modern physicist Albert Einstein: Both figures have become ciphers for ingenious thought and superior scientific reasoning, despite the fact that neither Copernicus’ calculations nor Einstein’s Theory of Relativity can be truly understood by non-experts. As such, the portrayals of both scientists appear in very varied contexts and are also used for marketing purposes.

Text

The history of how Copernicus has been received can be more closely determined using two concepts that play a key role in recent history: modernity and the nation. In historical science, people are now trying to use the term modern era as a relatively general name for a specific epoch. But the term was originally used as an evaluative term to demonstrate and celebrate the overcoming of the Middle Ages. In this context, Nicolaus Copernicus is cited as a key player – his astronomical calculations played a part in opening up the Church’s narrow worldview and thus opened a door to modernity. To this day, Copernicus is often referred to and used as a role model when it comes to conjuring up notions of progress, expansion, and modernization. In light of the ecological crises that this modernization has brought, French sociologist Bruno Latour has since asked whether there is not a need to question this narrative: “The new climatic regime is forcing us to a kind of Copernican counter-revolution – turning our attention back to the Earth.”2

Text

From a German-Polish perspective, in the 19th and 20th centuries these dimensions were superimposed with the debate about the nationality of Copernicus. Both Germans and Poles wanted to rank the scholar among the “great men” of their own national history. From a Polish perspective, this national culture of remembrance was especially significant during the 130 years when there was no Polish state. From the German viewpoint, Copernicus was increasingly drawn on as a way of legitimizing a hegemony in Europe. Initially this involved using cultural aspects, such as his native language; during the Nazi period, this even progressed to the pseudo-scientific “racial research”, as demonstrated by published articles from the period about Copernicus’ German “bloodline.” These debates about Nicolaus Copernicus’ national identity continue to this day online, albeit with less vigor. Thus, for example, the English Wikipedia entry on Copernicus is one of the website’s articles with the most protracted “edit wars.”

Copernicus memorial in Toruń with facemask during the COVID pandemic in August 2020. A-z-L, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0

Copernicus memorial in Toruń with facemask during the COVID pandemic in August 2020. A-z-L, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0

Text

When one considers this background, the 550th anniversary of Nicolaus Copernicus’s birth in 2023 takes on a new dimension. Anniversaries of his birth and memorial years have sparked intense discussions about Copernicus over the years. When one considers the history of how the scholar has been perceived, it is noticeable that the discussions are never just about the science itself or the history of science. Instead, these terms have been shaped by the pervading interests of the time, from the tension between modernity and the nation. As art historian Christopher Riopelle has stated, the Copernicus memorials that have been erected since the 19th century are also part of a general boom in memorials: Figures like Shakespeare, Michelangelo, Goethe, Schiller, and, of course, Copernicus, have been honored in this way because people across Europe were convinced that “the ‘genius’ of a great nation could be best expressed in their genius.”3 According to this theory, anniversaries do not just relate to history; instead, they are a historical development in their own right and, in this way, create their own part of history. As such, this will also be a recurring theme in the following discussions around the Copernicus Year 2023.

Text

English translation: LEaF Translations