The Polish celebrations to mark the anniversary of Copernicus’ birth in 1973 were widespread and impacted science, the general public, and international relations. An expensive feature movie about the life of Copernicus was one of the main features of the celebrations.

Text

The program to mark the 500th anniversary of Nicolaus Copernicus’ birth in Poland was broad-ranging and incorporated a number of different events and outcomes. According to cultural scientist Elisabeth Ritter, the Polish authorities worked on the staging of the Copernicus Year (“rok kopernika 1973”) “with all of the means they had available.”1 Part of the reason behind this related to the international perception of Poland: According to the plans of Edward Gierek (head of the Polish United Workers' Party [Polska Zjednoczona Partia Robotnicza] from 1970 onwards), the celebrations were intended to demonstrate the increasing role that Poland played in the world.

Text

“Intercopernicalia ’73” was one of the most extraordinary events. It was an international exchange week for students, and nothing comparable took place in either East or West Germany. It ran from September 14-17, in Toruń, with participants coming from universities in Poland, the Soviet Union, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, and Bulgaria. Students from Finland, France, and the USA also took part. The organizers met the expectations of the guests by incorporating the lectures and political rallies into a wide-ranging program of cultural events, designed to live up to western standards. These events included discos, a nighttime light show, fireworks, movie projections, and music, as well as concerts featuring Krzysztof Sadowski’s fusion-jazz combo and Wojciech Skowroński’s blues-rock band.

Text

The publications marking the Copernicus anniversary were aimed at the general public and were often available in different languages and sold overseas. The Land of Nicholas Copernicus book by Michał Rusinek is one example of this. It was richly illustrated with photographs by Magdalena Rusinek-Kwilecka and published by a New York publishing house in 1973. In this book, Copernicus is described as a product of his Polish homeland: The lively Hansa town of Toruń sparked a number of different interests in the young Nicolaus: As a student in Cracow, he is “likely” to have admired the medieval buildings. As such, Copernicus “would surely never have felt that his country was in any way forced to lag behind the rest of Europe.”2 Overseas Polish societies and associations, particularly those in the USA and Britain, were successful in spreading the idea of Copernicus as a Polish export. An article published in the New York Times on February 19, 1973, to mark Copernicus’ 500th anniversary serves as proof of the success of such initiatives – it describes Copernicus as “Poland’s greatest scientist.”3

Text

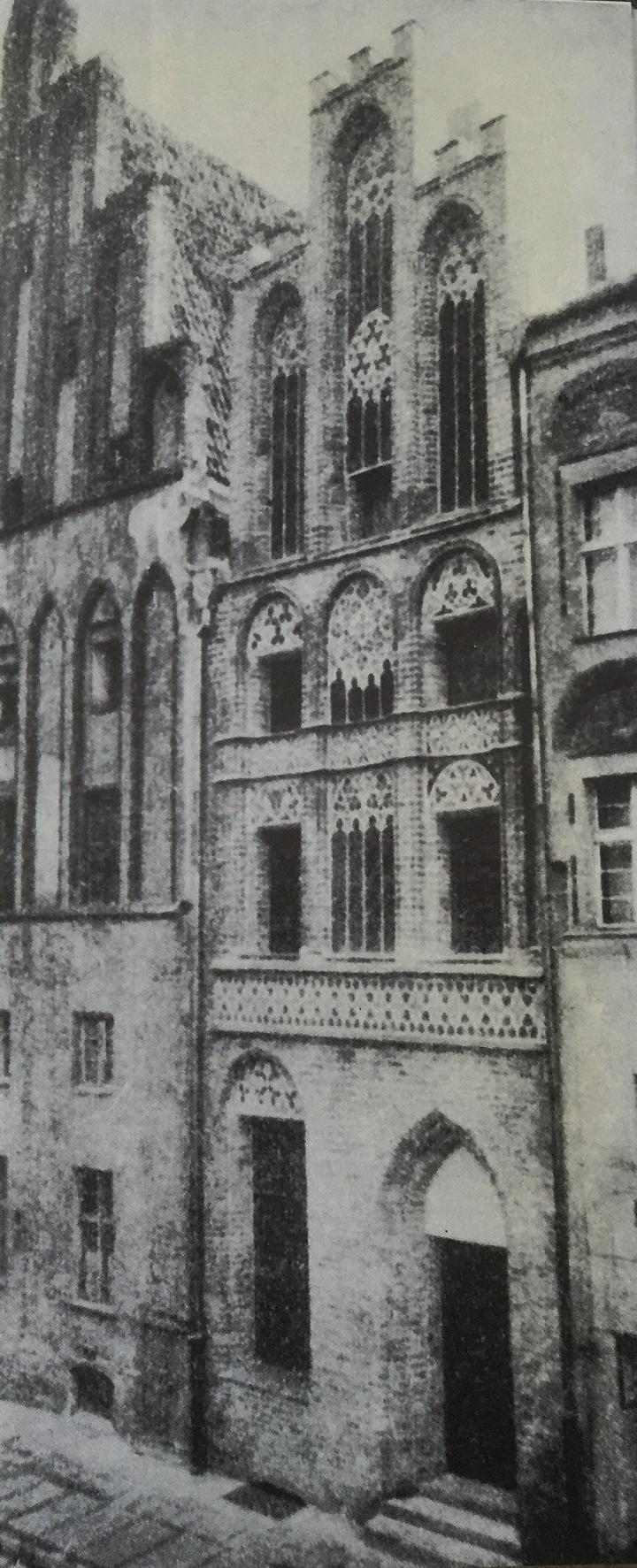

There was plenty on offer for the Polish population. The Copernicus House in Toruń’s old town was refurbished and its medieval façade was reconstructed. The building, which had been divided up into rental apartments when Toruń was known as the West Prussian town of Thorn, was opened to the public as a museum for the very first time. A modern planetarium was built in Olsztyn, where Copernicus spent many years of his life. The planetarium was ceremoniously opened on the 500th anniversary of his birth. Carl Zeiss Jena provided the projection technology and the building’s atrium featured a mosaic by Stefan Knapp – a Polish artist based in London, whose works were exhibited around the globe during this period. The scope of the Copernicus campaign in the Polish People’s Republic can be seen in the board game known as Turniej Kopernikowski [Copernicus Tournament] – it was also released in the 1973 anniversary year. American Copernicus expert Prof. Owen Gingerich, who took part in the science events in Poland in 1973, later reminisced that Copernicus was “ever-present”4 in Polish everyday life back then.

Text

The Polish world of science also focused its activities on Copernicus’ anniversary. In September 1973, the International Astronomical Union held a prestigious extraordinary general meeting in Warsaw. The Polish Academy of Sciences published a complete edition of the works of Copernicus to mark the anniversary year. It contained explanatory notes in six different languages, thus targeting an international audience. Astronomer Prof. Jerzy Dobrzycki, who was in charge of managing the project, had already cultivated good relations with Copernicus researchers Edward Rosen and Prof. Owen Gingerich from the United States. Contact was also made with the editors of the West German Copernicus complete works edition, for which work began at this time in Munich.

Text

Together with historian Marian Biskup, Dobrzycki also published a book entitled Nicolaus Copernicus. Gelehrter und Staatsbürger [Nicolaus Copernicus. Scholar and Citizen]. The book was aimed at a broad audience and multiple editions were printed in German and English. The book not only depicts Copernicus as an astronomer; he is also shown to be “a dedicated diplomat, an outstanding authority on administrative issues, a determined military advisor, a sought-after physician, and an oft-consulted expert in monetary affairs.”5 According to the book, the notion of Copernicus as a “quiet scholar”6 is one of the “falsifications of Copernicus’ image portrayed by flag-waving German chauvinism during the first half of the 20th century”7 , since Copernicus practiced all of these different roles within his fatherland of Prussia and, therefore, in allegiance to the Polish crown: “For all of his love for research, science, and philosophy, Kopernik was deeply rooted in the reality of the everyday. He felt a close and honest connection to his country’s problems, and he dedicated a large part of his life and talents to addressing these. Thus, Doctor Mikołaj Kopernik fully deserved to be called a good citizen of his homeland – Prusy Krolewskie – and the whole of the Polish state.”8

Still from the movie Copernicus with Andrzej Kopiczyński (left) playing the lead role. DEFA-Stiftung/Bauersfeld, Diestelmann / DEFA foundation/Bauersfeld, Diestelmann, Free access - no reuse

Still from the movie Copernicus with Andrzej Kopiczyński (left) playing the lead role. DEFA-Stiftung/Bauersfeld, Diestelmann / DEFA foundation/Bauersfeld, Diestelmann, Free access - no reuse

Text

These interpretations of Copernicus then entered popular media. Biskup and Dobrzycki served as advisors for the feature movie Copernicus,9 which, according to Elisabeth Ritter, was envisaged to be “one of the highlights of the celebrations”10 in Poland and, as a co-production with the East German movie company DEFA, was also intended for an East German audience. Astronomy was not the sole focus of the movie in which Andrzej Kopiczyński played the leading role. As a canon, Copernicus appears open to the needs of the common people. But, above all else, his role is that of a defender of Varmia and Allenstein Castle (Olsztyn) against the armies of the German Teutonic Order. The Teutonic Knights, or “zakon krzyżacki” as they are known in Poland, are characterized as being extremely brutal in the movie. Back then in Poland, they were seen as the precursors to Germany’s aspirations for great power; whereas in West Germany, the regional associations representing those who had been expelled from East and West Prussia continued to strongly identify with the Teutonic Order, seeing their “cultural achievements” as pioneering for their own “homeland.”

Text

The gloomy portrayal of the Catholic Church in the Copernicus movie is not mirrored in the book by Biskup and Dobrzycki. Lukas Watzenrode (played by Czesław Wołłejko), Copernicus’ uncle and Bishop of Varmia, appears as a bigoted and power-hungry clergyman; clergy are seen whipping up a crowd to lynch alleged heretics; and the appearance of the Church as an institution is consistently accompanied by foreboding music. The Church even foils the happiness of the protagonist’s personal life: The movie imagines a love affair between Copernicus and Anna Schilling (Barbara Wrzesińska) – a distant relative who is known to have lived with Copernicus in the cathedral chapter in Frauenburg as his housekeeper in 1538/39. The bishop, Johannes Dantiscus, forces Copernicus to send Anna away, and this is depicted in the movie as a tragic conclusion to their intimate relationship. The relatable humanity of the Copernicus shown in the movie is indicative of how the Polish People’s Republic attempted to lend the historical figure a modern-day presence during the anniversary year of 1973.

Text

English translation: LEaF Translations