The actor Hanna Schygulla was 30 years old when she first met Gottliebe von Lehndorff in 1973. The scene of the encounter: the artists' colony in the old Peterskirchen vicarage, east of Munich. They lived there for thirteen years, their apartments backing onto each other. Despite their age difference, they had many things in common, not least the experience of losing their homeland. In the podcast, the years they shared at Peterskirchen come back to life.

Text

Hanna Schygulla reads12

“Someone had told me about an artists' community on the other side of the Inn, in an old vicarage. It was situated just outside the village boundary of Peterskirchen and could be seen from a distance – painted a beautiful sienna red, it somehow loooked rather Italian, nestled in the hilly landscape. In one wing lived a family of musicians who occasionally experimented with Friedrich Gulda on instruments they’d made themselves, among sculptures they’d also created. The main house was home to two young painters and photographers and the world-famous beauty, Veruschka, who went far beyond a modeling career and created her own amazing body art. Her mother, the Countess von Lehndorff, also lived in the main house with her partner Fritz, a former mathematics teacher, who organized ambitious philosophical adventure camps based on Heidegger's existentialism.”

“Someone had told me about an artists' community on the other side of the Inn, in an old vicarage. It was situated just outside the village boundary of Peterskirchen and could be seen from a distance – painted a beautiful sienna red, it somehow loooked rather Italian, nestled in the hilly landscape. In one wing lived a family of musicians who occasionally experimented with Friedrich Gulda on instruments they’d made themselves, among sculptures they’d also created. The main house was home to two young painters and photographers and the world-famous beauty, Veruschka, who went far beyond a modeling career and created her own amazing body art. Her mother, the Countess von Lehndorff, also lived in the main house with her partner Fritz, a former mathematics teacher, who organized ambitious philosophical adventure camps based on Heidegger's existentialism.”

The old vicarage, 1970s. Ostpreußisches Landesmuseum, Free access - no reuse

The old vicarage, 1970s. Ostpreußisches Landesmuseum, Free access - no reuse

Text

Ulla Lachauer

Those were the years after the student revolt. Hanna Schygulla was thirty at the time, at the beginning of her great career as an actress. After a few films directed by Rainer Werner Fassbinder, she was looking for a peaceful existence in the countryside. The artists' colony in the old vicarage near Peterskirchen, east of Munich, seemed to be the right place for her. There she met Gottliebe von Lehndorff – from the very first moment they liked each other.

Hanna Schygulla reads

"It was Countess von Lehndorff who opened the door for me on that first day. I’d just pulled into that wonderfully half-wild courtyard and still had Pink Floyd’s 'all in all...it' s just another brick in the wall' ringing in my ears from the car radio.”

'I’m Gottliebe,' she says to me, leaving out the title “countess” and also the “von” from her name.

This name, which I have never heard before, makes me think: "I wonder if she has a God whom she loves or who loves her?"

Those were the years after the student revolt. Hanna Schygulla was thirty at the time, at the beginning of her great career as an actress. After a few films directed by Rainer Werner Fassbinder, she was looking for a peaceful existence in the countryside. The artists' colony in the old vicarage near Peterskirchen, east of Munich, seemed to be the right place for her. There she met Gottliebe von Lehndorff – from the very first moment they liked each other.

Hanna Schygulla reads

"It was Countess von Lehndorff who opened the door for me on that first day. I’d just pulled into that wonderfully half-wild courtyard and still had Pink Floyd’s 'all in all...it' s just another brick in the wall' ringing in my ears from the car radio.”

'I’m Gottliebe,' she says to me, leaving out the title “countess” and also the “von” from her name.

This name, which I have never heard before, makes me think: "I wonder if she has a God whom she loves or who loves her?"

Text

Ulla Lachauer

Hanna Schygulla was to later describe this moment in 1973 in a short, poetic text entitled "Meine Freundin Gottliebe” (My friend Gottliebe).

Hanna Schygulla reads

"I look for the first time into that open face full of quiet melancholy and traces of Prussian firmness, which dissolves in an instant as if suddenly in soft focus, and she gives me her most beautiful smile. Throughout the following thirteen years, that smile will still often enchant me and make it quite easy for me and everyone else in the vicarage to love this Gottliebe, this “God love”, that is yet so human and close."

Hanna Schygulla was to later describe this moment in 1973 in a short, poetic text entitled "Meine Freundin Gottliebe” (My friend Gottliebe).

Hanna Schygulla reads

"I look for the first time into that open face full of quiet melancholy and traces of Prussian firmness, which dissolves in an instant as if suddenly in soft focus, and she gives me her most beautiful smile. Throughout the following thirteen years, that smile will still often enchant me and make it quite easy for me and everyone else in the vicarage to love this Gottliebe, this “God love”, that is yet so human and close."

Ulla Lachauer

This text, which Hanna Schygulla wrote in 2010 in her adopted home of Paris, is already a thing of the past. Our conversation3 takes place in her Berlin apartment, shortly after the Russian invasion of. The artists' colony in Peterskirchen and that wild time of social upheaval are now half a century ago.

Hanna Schygulla

"At that time, no one yet thought that the world was really on the brink of extinction, that is, on the brink of its own self-generated catastrophe. Yes, now a war on top of everything else. A second Hitler has virtually risen from the dead, of the Russian variety."

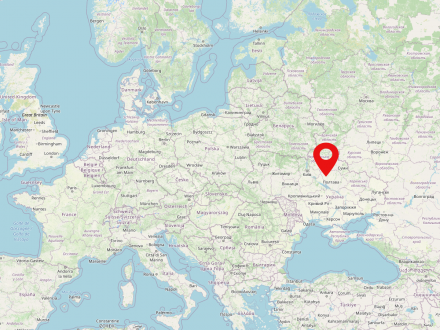

This text, which Hanna Schygulla wrote in 2010 in her adopted home of Paris, is already a thing of the past. Our conversation3 takes place in her Berlin apartment, shortly after the Russian invasion of

Ukraine

ukr. Ukrajina, deu. Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in eastern Europe inhabited by about 42 million people. Kiev is the capital and also the greatest city of Ukraine. The country has been independent since 1991. The Dnieper River is the longest river in Ukraine.

Hanna Schygulla

"At that time, no one yet thought that the world was really on the brink of extinction, that is, on the brink of its own self-generated catastrophe. Yes, now a war on top of everything else. A second Hitler has virtually risen from the dead, of the Russian variety."

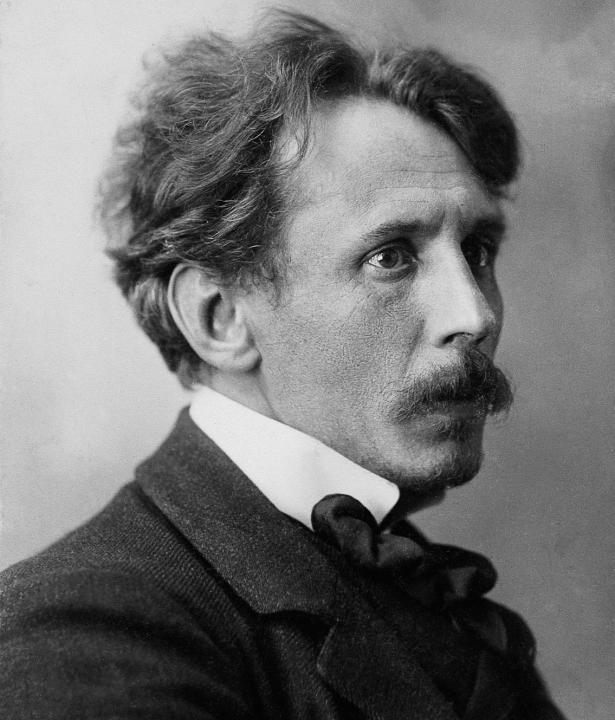

Gottliebe von Lehndorff, early 1960s. Ostpreußisches Landesmuseum, Free access - no reuse

Gottliebe von Lehndorff, early 1960s. Ostpreußisches Landesmuseum, Free access - no reuse

Text

Ulla Lachauer

Hanna Schygulla experienced the horrors of National Socialism as a little girl when she fled with her mother in 1945.4 In Gottliebe von Lehndorff, she met a contemporary witness of those times who, by resisting Hitler, had put everything on the line.

Hanna Schygulla

"The time I spent at the vicarage was about thirteen years, well, she would have been 65 or 63 then. So there were thirty years between us, even a bit more. But she was always so open – though, on the other hand, she was also unreachable on certain levels. She was also tragically involved in contemporary history. Heroic, tragic, and certainly very much burdened with guilt."

Ulla Lachauer

The young actress had an intuitive sense of this tragedy. At first, Hanna Schygulla didn't know much about Gottlieb's involvement in the preparations for the assassination of Hitler. Only that her husband, Heinrich Graf von Lehndorff, was executed as a conspirator in 1944. And that the castle in Masuria where the count's family had lived was called Steinort. In the large living room of the vicarage hung a huge tapestry – one of the last relics from this lost homeland.

Hanna Schygulla experienced the horrors of National Socialism as a little girl when she fled

Upper Silesia

deu. Oberschlesien, pol. Górny Śląsk

Upper Silesia (Polish Górny Śląsk, Czech Horní Slezsko) is the southeastern part of Silesia in modern Poland and the Czech Republic. The area lies on the Odra River and a part of the eastern Sudeten Mountains. Opole (Polish: Oppeln) is regarded as the historical capital of Upper Silesia.

Hanna Schygulla

"The time I spent at the vicarage was about thirteen years, well, she would have been 65 or 63 then. So there were thirty years between us, even a bit more. But she was always so open – though, on the other hand, she was also unreachable on certain levels. She was also tragically involved in contemporary history. Heroic, tragic, and certainly very much burdened with guilt."

Ulla Lachauer

The young actress had an intuitive sense of this tragedy. At first, Hanna Schygulla didn't know much about Gottlieb's involvement in the preparations for the assassination of Hitler. Only that her husband, Heinrich Graf von Lehndorff, was executed as a conspirator in 1944. And that the castle in Masuria where the count's family had lived was called Steinort. In the large living room of the vicarage hung a huge tapestry – one of the last relics from this lost homeland.

The living room of the Peterskirchen vicarage; the candlestick probably came from Steinort Castle. Ostpreußisches Landesmuseum, Free access - no reuse

The living room of the Peterskirchen vicarage; the candlestick probably came from Steinort Castle. Ostpreußisches Landesmuseum, Free access - no reuse

Text

Ulla Lachauer

In the Peterskirchen vicarage, people lived in the here and now. Gottliebe Lehndorff had bought it in the 1960s – for herself and her partner, the performance artist Fritz Schranz. His courses on Plato, Nietzsche and Heidegger and the adventurous philosophy camps he ran were widely known.

Hanna Schygulla

"We regarded Fritz Schranz, of course, as a total original. He was the one who developed it all back then, together with others. He had a very strange appearance... Fritz didn't look very German. He was dark, very dark. His hair was frizzy – you rarely see that in Bavaria – and he’d tie it up in a Mozart braid. He had his writing chapel out the back. The vicarage used to be an ecclesiastical place. And he would regularly withdraw there as if on a retreat to write. He had probably also been an altar boy and all the rest. So in his camps he liked to bring in something of the ritual of the mass, through the back door so to speak."

Ulla Lachauer

"Every human being is a philosopher and priest" was his credo. Fritz Schranz inspired the cultural scene of the time: the pianist Friedrich Gulda and the theater director Peter Zadek came to visit, as did the poet Thomas Bernhard, the actress Ingrid Caven, and the famous couple Uschi Obermeier and Rainer Langhans from Commune 1 in Berlin. Rainer Werner Fassbinder also made regular trips to Peterskirchen.

It was an intensive time of searching and trying things out. The desire for something new also united women as different as Hanna Schygulla and Gottliebe von Lehndorff.

In the Peterskirchen vicarage, people lived in the here and now. Gottliebe Lehndorff had bought it in the 1960s – for herself and her partner, the performance artist Fritz Schranz. His courses on Plato, Nietzsche and Heidegger and the adventurous philosophy camps he ran were widely known.

Hanna Schygulla

"We regarded Fritz Schranz, of course, as a total original. He was the one who developed it all back then, together with others. He had a very strange appearance... Fritz didn't look very German. He was dark, very dark. His hair was frizzy – you rarely see that in Bavaria – and he’d tie it up in a Mozart braid. He had his writing chapel out the back. The vicarage used to be an ecclesiastical place. And he would regularly withdraw there as if on a retreat to write. He had probably also been an altar boy and all the rest. So in his camps he liked to bring in something of the ritual of the mass, through the back door so to speak."

Ulla Lachauer

"Every human being is a philosopher and priest" was his credo. Fritz Schranz inspired the cultural scene of the time: the pianist Friedrich Gulda and the theater director Peter Zadek came to visit, as did the poet Thomas Bernhard, the actress Ingrid Caven, and the famous couple Uschi Obermeier and Rainer Langhans from Commune 1 in Berlin. Rainer Werner Fassbinder also made regular trips to Peterskirchen.

It was an intensive time of searching and trying things out. The desire for something new also united women as different as Hanna Schygulla and Gottliebe von Lehndorff.

Fritz Schranz and Gottliebe von Lehndorff in the vicarage garden, 1980s. Ostpreußisches Landesmuseum, Free access - no reuse

Fritz Schranz and Gottliebe von Lehndorff in the vicarage garden, 1980s. Ostpreußisches Landesmuseum, Free access - no reuse

Text

Hanna Schygulla

"That definitely connected us. Because I always liked to set out for new shores, so to speak. And I was also at the very beginning of a new movement in German film, and that unprejudiced, different way of doing things was my entry into professional life. And these things, she already had an affinity for them, because she also had a partner at her side who was eager to experiment. Who, by the way, came from a completely different class. She was an aristocrat, and Fritz Schranz came from the proletariat. And I came half from the proletariat on my father's side, and on my mother's side there was already something of an aspiring petty bourgeoisie."

Ulla Lachauer

Class barriers were no longer to play a role. In the realm of imagination, everyone was equal. And the old vicarage with its overgrown garden was so spacious that everyone had room for their art and their individual needs. Hanna Schygulla led a "migratory life," as she says. During these years, her career virtually exploded. With Fassbinder she made "Effi Briest", "Die Ehe der Maria Braun", "Lilli Marleen", she appeared on stage under the direction of George Tabori. And she always returned to the rural oasis of Peterskirchen.

"That definitely connected us. Because I always liked to set out for new shores, so to speak. And I was also at the very beginning of a new movement in German film, and that unprejudiced, different way of doing things was my entry into professional life. And these things, she already had an affinity for them, because she also had a partner at her side who was eager to experiment. Who, by the way, came from a completely different class. She was an aristocrat, and Fritz Schranz came from the proletariat. And I came half from the proletariat on my father's side, and on my mother's side there was already something of an aspiring petty bourgeoisie."

Ulla Lachauer

Class barriers were no longer to play a role. In the realm of imagination, everyone was equal. And the old vicarage with its overgrown garden was so spacious that everyone had room for their art and their individual needs. Hanna Schygulla led a "migratory life," as she says. During these years, her career virtually exploded. With Fassbinder she made "Effi Briest", "Die Ehe der Maria Braun", "Lilli Marleen", she appeared on stage under the direction of George Tabori. And she always returned to the rural oasis of Peterskirchen.

Gottliebe von Lehndorff and Hanna Schygulla on one of their walks, May 1980. Ostpreußisches Landesmuseum, Free access - no reuse

Gottliebe von Lehndorff and Hanna Schygulla on one of their walks, May 1980. Ostpreußisches Landesmuseum, Free access - no reuse

Gottliebe von Lehndorff and Hanna Schygulla on one of their walks, May 1980. Ostpreußisches Landesmuseum, Free access - no reuse

Gottliebe von Lehndorff and Hanna Schygulla on one of their walks, May 1980. Ostpreußisches Landesmuseum, Free access - no reuse

Text

Hanna Schygulla reads

"It was to be a whole thirteen years of happy neighborliness among us loners in the vicarage, who only had to cross the hall to be with the others in the house, and the Countess was also completely part of it. She may have been much older, but she did not have the usual limitations and prejudices of the previous generation. She had this readiness for the new – it’s a characteristic of people who’ve been uprooted."

Ulla Lachauer

Hanna Schygulla and Gottliebe von Lehndorff shared the experience of uprootedness. The two hardly ever talked about it. The actress was still very young at the time. She had left behind the refugee child that she once was.5

Hanna Schygulla

"Some things I never talked about, for example how my mother and I had taken one of the last trains, and everything my mother told me about that time – that there were already Russians on the train. A drunk Russian man came into the compartment and said, 'I'll throw them out of the windows, the Nazi spawn.’ That was me – I was Nazi spawn. I suddenly started speaking Polish, even though I only knew a few words. ‘Bendzemi jest?' 'Is there anything to eat?' And then the Russian thought, well, that's a Polish kid, and went on his way."

"It was to be a whole thirteen years of happy neighborliness among us loners in the vicarage, who only had to cross the hall to be with the others in the house, and the Countess was also completely part of it. She may have been much older, but she did not have the usual limitations and prejudices of the previous generation. She had this readiness for the new – it’s a characteristic of people who’ve been uprooted."

Ulla Lachauer

Hanna Schygulla and Gottliebe von Lehndorff shared the experience of uprootedness. The two hardly ever talked about it. The actress was still very young at the time. She had left behind the refugee child that she once was.5

Hanna Schygulla

"Some things I never talked about, for example how my mother and I had taken one of the last trains, and everything my mother told me about that time – that there were already Russians on the train. A drunk Russian man came into the compartment and said, 'I'll throw them out of the windows, the Nazi spawn.’ That was me – I was Nazi spawn. I suddenly started speaking Polish, even though I only knew a few words. ‘Bendzemi jest?' 'Is there anything to eat?' And then the Russian thought, well, that's a Polish kid, and went on his way."

Hanna Schygulla at the age of five, 1948. Hanna Schygulla, Free access - no reuse

Hanna Schygulla at the age of five, 1948. Hanna Schygulla, Free access - no reuse

Text

Ulla Lachauer

Neither Hanna nor her friend Gottliebe talked about their traumatic experiences. What they had in common was that they came from a world to which Polish belonged – in Upper Silesia very much like in Masuria.

Hanna Schygulla

“We were kindred spirits in a certain respect – related, but not in a mother-daughter sense. Instead, I think I reminded her in many ways of these Polish people with whom she had a lot of contact. And she always said that she liked the Poles in so much. They were such warm-hearted people. She often told me that."

Ulla Lachauer

Hanna Schygulla's face awakened memories in Gottliebe of the Polish farm workers and day laborers on the Steinort estate. The closeness to them had remained in Gottliebe's memory; her husband Heinrich had also had an affection for them – "Heini," as she still called him in conversations with people she knew.

Neither Hanna nor her friend Gottliebe talked about their traumatic experiences. What they had in common was that they came from a world to which Polish belonged – in Upper Silesia very much like in Masuria.

Hanna Schygulla

“We were kindred spirits in a certain respect – related, but not in a mother-daughter sense. Instead, I think I reminded her in many ways of these Polish people with whom she had a lot of contact. And she always said that she liked the Poles in

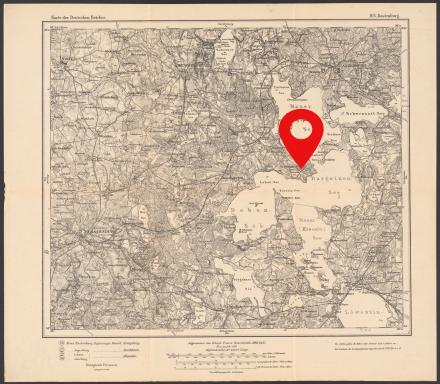

Sztynort

deu. Steinort, deu. Groß Steinort

The village of Sztynort is located in the north of the Masurian Lake District on the Jez Peninsula between Jezioro Mamry, Jezioro Dargin and Jezioro Dobskie. Until 1928 the village was called Groß Steinort, then Steinort.

Ulla Lachauer

Hanna Schygulla's face awakened memories in Gottliebe of the Polish farm workers and day laborers on the Steinort estate. The closeness to them had remained in Gottliebe's memory; her husband Heinrich had also had an affection for them – "Heini," as she still called him in conversations with people she knew.

Potato harvest on the outlying estate of Taberlack, 1930s, from a Lehndorff family album. Ostpreußisches Landesmuseum, Free access - no reuse

Potato harvest on the outlying estate of Taberlack, 1930s, from a Lehndorff family album. Ostpreußisches Landesmuseum, Free access - no reuse

Text

Hanna Schygulla

"That was – how shall we say – lordship of the manor with a human face. It was not an exploitative relationship, not “we are the masters here and you have to serve us”. Heini was also very close to nature. I never knew him. But from what she told me, he knew everything about nature, and he loved it, too."

Ulla Lachauer

Gottliebe said little about her marriage. But she liked to talk about her first great love – an older man named Bogislav Krahmer, a veterinarian, to whom she gave her heart as a seventeen-year-old high school student. That was back in Dresden, when she was still called Gottliebe Gräfin von Kalnein. She often remembered their lovestruck summer together in 1931 – a happy and formative time. It ended abruptly because Gottliebe's parents put a stop to the relationship. In their eyes, Bogislav Krahmer was below her social standing, and he was Jewish.

"That was – how shall we say – lordship of the manor with a human face. It was not an exploitative relationship, not “we are the masters here and you have to serve us”. Heini was also very close to nature. I never knew him. But from what she told me, he knew everything about nature, and he loved it, too."

Ulla Lachauer

Gottliebe said little about her marriage. But she liked to talk about her first great love – an older man named Bogislav Krahmer, a veterinarian, to whom she gave her heart as a seventeen-year-old high school student. That was back in Dresden, when she was still called Gottliebe Gräfin von Kalnein. She often remembered their lovestruck summer together in 1931 – a happy and formative time. It ended abruptly because Gottliebe's parents put a stop to the relationship. In their eyes, Bogislav Krahmer was below her social standing, and he was Jewish.

Gottliebe Gräfin von Kalnein, 1931, from a family album. Ostpreußisches Landesmuseum, Free access - no reuse

Gottliebe Gräfin von Kalnein, 1931, from a family album. Ostpreußisches Landesmuseum, Free access - no reuse

Text

Hanna Schygulla

"She was forcibly separated from her lover. So that, I think, is a key to why she rebelled so passionately against Hitler and maybe, I think, in-spired Heini to do this, too. I think if Gottliebe had not been separated from her first love, she might not have been like that either. I almost be-lieve that she was a driving force. But that is a guess. Because Gottliebe could already exert great influence, she had charisma, as they say ."

Ulla Lachauer

The persecution and extermination of the Jews affected her personally, Hanna Schygulla suspects. Besides, Gottliebe had more of a rebellious nature, unlike her self-contained, cheerful Heinrich. Perhaps it was she who led the way, who urged resistance?

Hanna Schygulla

"And it might well be that all this upset her deeply afterwards, that she said to herself: 'My God, what have we done here? I mean, the assassination attempt failed. Heini was hanged, I was separated from the children. All that.'"

Hanna Schygulla

"That's probably why she talked so much about fate. And then Fritz came and told her: ‘Listen, fate is a term that is not creative.’ He would probably have said something like that. ‘Just think of yourself as the sum total of circumstances and what you've made of them, and of the opportunities you've used or not used in your development.’"

Ulla Lachauer

Being creative as therapy, disentangling oneself from the past, becoming free. Perhaps that was what Gottliebe was looking for in Peterskirchen?

"She was forcibly separated from her lover. So that, I think, is a key to why she rebelled so passionately against Hitler and maybe, I think, in-spired Heini to do this, too. I think if Gottliebe had not been separated from her first love, she might not have been like that either. I almost be-lieve that she was a driving force. But that is a guess. Because Gottliebe could already exert great influence, she had charisma, as they say ."

Ulla Lachauer

The persecution and extermination of the Jews affected her personally, Hanna Schygulla suspects. Besides, Gottliebe had more of a rebellious nature, unlike her self-contained, cheerful Heinrich. Perhaps it was she who led the way, who urged resistance?

Hanna Schygulla

"And it might well be that all this upset her deeply afterwards, that she said to herself: 'My God, what have we done here? I mean, the assassination attempt failed. Heini was hanged, I was separated from the children. All that.'"

Hanna Schygulla

"That's probably why she talked so much about fate. And then Fritz came and told her: ‘Listen, fate is a term that is not creative.’ He would probably have said something like that. ‘Just think of yourself as the sum total of circumstances and what you've made of them, and of the opportunities you've used or not used in your development.’"

Ulla Lachauer

Being creative as therapy, disentangling oneself from the past, becoming free. Perhaps that was what Gottliebe was looking for in Peterskirchen?

An art event in the Peterskirchen courtyard, 1970s, Fritz Schranz is second from left. Ostpreußisches Landesmuseum, Free access - no reuse

An art event in the Peterskirchen courtyard, 1970s, Fritz Schranz is second from left. Ostpreußisches Landesmuseum, Free access - no reuse

Text

Hanna Schygulla

"Her true soul, if you want to use the word in such an old-fashioned way, always wanted to spread its wings.”

Hanna Schygulla

„Sie hat sehr viel in der Zeit die Nocturnes von Schubert gespielt. Bam, Bam Bampadam, also diese ganz, tamtadati, tidadi, tiptadidadidada, pam, bam, bampadam. Die sind ja sehr melancholisch auch, die Nocturnes von Schubert.“

Ulla Lachauer

At certain moments, the old 18th-century vicarage seemed to Gottliebe to be similar to Steinort Castle – imposing, dignified, cultivated.

Hanna Schygulla

"And there was also a library, as befits a manorial and cultural house-hold. There were a lot of books lying around. Gottliebe was not one to seek salvation in culture or intellectuality. With her it was more about being or not being. So there were moments when she simply wasn't there. And then she was always glad when she came back to the now."

Ulla Lachauer

In a small private film sequence from the 70s, we see the friends Gottliebe and Hanna back-to-back. They turn to each other, sometimes to the camera. In the play, Gottliebe shows her different faces, her rapidly changing moods.

"Her true soul, if you want to use the word in such an old-fashioned way, always wanted to spread its wings.”

Hanna Schygulla

„Sie hat sehr viel in der Zeit die Nocturnes von Schubert gespielt. Bam, Bam Bampadam, also diese ganz, tamtadati, tidadi, tiptadidadidada, pam, bam, bampadam. Die sind ja sehr melancholisch auch, die Nocturnes von Schubert.“

Ulla Lachauer

At certain moments, the old 18th-century vicarage seemed to Gottliebe to be similar to Steinort Castle – imposing, dignified, cultivated.

Hanna Schygulla

"And there was also a library, as befits a manorial and cultural house-hold. There were a lot of books lying around. Gottliebe was not one to seek salvation in culture or intellectuality. With her it was more about being or not being. So there were moments when she simply wasn't there. And then she was always glad when she came back to the now."

Ulla Lachauer

In a small private film sequence from the 70s, we see the friends Gottliebe and Hanna back-to-back. They turn to each other, sometimes to the camera. In the play, Gottliebe shows her different faces, her rapidly changing moods.

Screenshot from “Die große Evolution”, documentary material from the 1970s. Matthias Luthardt, www.matthias-luthardt.de, Free access - no reuse

Screenshot from “Die große Evolution”, documentary material from the 1970s. Matthias Luthardt, www.matthias-luthardt.de, Free access - no reuse

Screenshot from “Die große Evolution”, documentary material from the 1970s. Matthias Luthardt, www.matthias-luthardt.de, Free access - no reuse

Screenshot from “Die große Evolution”, documentary material from the 1970s. Matthias Luthardt, www.matthias-luthardt.de, Free access - no reuse

Text

Hanna Schygulla

"That's how Gottliebe looked when she was a little petrified. But she still went along with it, and here it dissolves into that laugh, which always enchanted me so much. That's when she became wholly herself, completely soft, and that charm that was her hallmark would come out."

Ulla Lachauer

Fritz Schranz6 , Gottliebe's companion in life, is also immortalized in the film document. Considerably younger than her, he looks like a big child, full of energy, constantly on the move.

Hanna Schygulla

"Fritz was an original. He also had a childlike side that probably touched her and he totally adored Gottliebe. For him, she was the ‘fine lady’, and she certainly liked that. And at the same time, he was her teacher. Whether she was so happy with that, I don't know. I don't think that this overly heady stuff really did her any good."

"That's how Gottliebe looked when she was a little petrified. But she still went along with it, and here it dissolves into that laugh, which always enchanted me so much. That's when she became wholly herself, completely soft, and that charm that was her hallmark would come out."

Ulla Lachauer

Fritz Schranz6 , Gottliebe's companion in life, is also immortalized in the film document. Considerably younger than her, he looks like a big child, full of energy, constantly on the move.

Hanna Schygulla

"Fritz was an original. He also had a childlike side that probably touched her and he totally adored Gottliebe. For him, she was the ‘fine lady’, and she certainly liked that. And at the same time, he was her teacher. Whether she was so happy with that, I don't know. I don't think that this overly heady stuff really did her any good."

Gottliebe von Lehndorff’s transcript of a lecture on Heidegger by Fritz Schranz. Ostpreußisches Landesmuseum, Free access - no reuse

Gottliebe von Lehndorff’s transcript of a lecture on Heidegger by Fritz Schranz. Ostpreußisches Landesmuseum, Free access - no reuse

Text

Hanna Schygulla

"He probably loved her more than she loved him, I think. She was devoted to him, for sure, but she also suffered a lot with him. He wasn't very agreeable to her, actually. He was just too much. He was such a firebrand and so obsessive. She would probably have trodden more gently, more cautiously on her own."

Ulla Lachauer

Their relationship lasted more than a quarter of a century – a long time compared to the seven years Gottliebe spent with Heinrich von Lehndorff. Nowhere did she stay longer than in Peterskirchen; the vicarage was the center of her life until her death in 1993. One of her four daughters also lived there for a time, Vera, famous worldwide as "Veruschka".

"He probably loved her more than she loved him, I think. She was devoted to him, for sure, but she also suffered a lot with him. He wasn't very agreeable to her, actually. He was just too much. He was such a firebrand and so obsessive. She would probably have trodden more gently, more cautiously on her own."

Ulla Lachauer

Their relationship lasted more than a quarter of a century – a long time compared to the seven years Gottliebe spent with Heinrich von Lehndorff. Nowhere did she stay longer than in Peterskirchen; the vicarage was the center of her life until her death in 1993. One of her four daughters also lived there for a time, Vera, famous worldwide as "Veruschka".

Gottliebe von Lehndorff and her daughter Vera von Lehndorff, early 1960s. Ostpreußisches Landesmuseum, Free access - no reuse

Gottliebe von Lehndorff and her daughter Vera von Lehndorff, early 1960s. Ostpreußisches Landesmuseum, Free access - no reuse

Text

Hanna Schygulla

"Gottliebe was never a mother in the way one imagines a mother to be, a refuge of 'Come to me, little ones. With me you are at home.' Instead, she was quite disconnected from the children. In some ways, life with children was like a garden she’d never really asked for. Vera was there a lot, because she was probably closest to her mother through the artistic side of things."

Ulla Lachauer

After her international career as a model, Vera von Lehndorff had largely withdrawn from the public eye and devoted herself to her own projects. She and her lifelong friend Holger Trülzsch were pioneers of "body art," developing unique, expressive body paintings. Many were created in the old vicarage in Peterskirchen.

Hanna Schygulla

"Gottliebe, of course, had a special relationship with Vera. But who wouldn't have that in the family, because it was so much in the public eye. And Vera also went her own way. And she always hoped that Vera would come out of these periodic depressions. And she herself knew what that was. She always saw Vera as a very vulnerable person."

Ulla Lachauer

Vera von Lehndorff herself spoke publicly about her bouts of depression several times. The trauma of her beloved father’s execution burdened her throughout her life, and these mental hardships were at the same time the source of her art.

Hanna Schygulla also found space for her own creativity in the Peterskirchen vicarage. In 1979 she made some experimental short films there. In front of the camera she staged dreams that she had noted down after waking up.7 "Dream Protocols" – her friend Gottliebe was also fascinated by the idea.

Hanna Schygulla

"Yes, one time we also filmed a dream sequence together. What was it again? Anyway, we laughed so much afterwards. It was always connected with lots of laughter. That's what I mean – she was also up for all kinds of fantasy games; that kind of thing always interested her."

"Gottliebe was never a mother in the way one imagines a mother to be, a refuge of 'Come to me, little ones. With me you are at home.' Instead, she was quite disconnected from the children. In some ways, life with children was like a garden she’d never really asked for. Vera was there a lot, because she was probably closest to her mother through the artistic side of things."

Ulla Lachauer

After her international career as a model, Vera von Lehndorff had largely withdrawn from the public eye and devoted herself to her own projects. She and her lifelong friend Holger Trülzsch were pioneers of "body art," developing unique, expressive body paintings. Many were created in the old vicarage in Peterskirchen.

Hanna Schygulla

"Gottliebe, of course, had a special relationship with Vera. But who wouldn't have that in the family, because it was so much in the public eye. And Vera also went her own way. And she always hoped that Vera would come out of these periodic depressions. And she herself knew what that was. She always saw Vera as a very vulnerable person."

Ulla Lachauer

Vera von Lehndorff herself spoke publicly about her bouts of depression several times. The trauma of her beloved father’s execution burdened her throughout her life, and these mental hardships were at the same time the source of her art.

Hanna Schygulla also found space for her own creativity in the Peterskirchen vicarage. In 1979 she made some experimental short films there. In front of the camera she staged dreams that she had noted down after waking up.7 "Dream Protocols" – her friend Gottliebe was also fascinated by the idea.

Hanna Schygulla

"Yes, one time we also filmed a dream sequence together. What was it again? Anyway, we laughed so much afterwards. It was always connected with lots of laughter. That's what I mean – she was also up for all kinds of fantasy games; that kind of thing always interested her."

Notes of Gottliebe von Lehndorff, mid-1970s. Ostpreußisches Landesmuseum, Free access - no reuse

Notes of Gottliebe von Lehndorff, mid-1970s. Ostpreußisches Landesmuseum, Free access - no reuse

Text

Ulla Lachauer

Gottliebe von Lehndorff, for her part, wrote down and painted dreams; some of her intimate "dream protocols" are still lying – as yet unsorted – in the depot of the East Prussian Regional Museum in Lüneburg. Hanna Schygulla called her autobiography "Wach auf und träume” (Wake up and dream). This is how she wanted to live, this is what she wanted to convey as an actress.

Hanna Schygulla

"The most intimate is always the most valuable – and the most interesting. And that is also what connects us all. Not the labels, the external existence."

Ulla Lachauer

In this sense, the two women were connected. An unspoken affinity in a milieu and a time where the private was considered political.

Hanna Schygulla

"I think back to Peterskirchen with a certain, yes, with a certain wistful-ness. It was actually a very special time."

Ulla Lachauer

It is the long walks together that Hanna Schygulla remembers with par-ticular fondness.

Hanna Schygulla reads

"Through the forests already delicately thinned by the first wave of forest dieback, or in the valley where the Ur flowed, which would only become visible in spring as a small stream, or walking to the farmer to get milk and eggs... or to the jetty on one of the small moraine lakes, and settling there and breathing in pure nature."

Gottliebe von Lehndorff, for her part, wrote down and painted dreams; some of her intimate "dream protocols" are still lying – as yet unsorted – in the depot of the East Prussian Regional Museum in Lüneburg. Hanna Schygulla called her autobiography "Wach auf und träume” (Wake up and dream). This is how she wanted to live, this is what she wanted to convey as an actress.

Hanna Schygulla

"The most intimate is always the most valuable – and the most interesting. And that is also what connects us all. Not the labels, the external existence."

Ulla Lachauer

In this sense, the two women were connected. An unspoken affinity in a milieu and a time where the private was considered political.

Hanna Schygulla

"I think back to Peterskirchen with a certain, yes, with a certain wistful-ness. It was actually a very special time."

Ulla Lachauer

It is the long walks together that Hanna Schygulla remembers with par-ticular fondness.

Hanna Schygulla reads

"Through the forests already delicately thinned by the first wave of forest dieback, or in the valley where the Ur flowed, which would only become visible in spring as a small stream, or walking to the farmer to get milk and eggs... or to the jetty on one of the small moraine lakes, and settling there and breathing in pure nature."

The photograph of Gottliebe von Lehndorff on Hanna Schygulla’s “Totentisch” (table of the dead). Hanna Schygulla, Free access - no reuse

The photograph of Gottliebe von Lehndorff on Hanna Schygulla’s “Totentisch” (table of the dead). Hanna Schygulla, Free access - no reuse

Text

Hanna Schygulla

"Now the picture I took of Gottliebe on the jetty on one of those golden days has pride of place on my ‘table of the dead’, in the company of all those others who went before me, people who enriched my life and whom I do not want to forget."

"Now the picture I took of Gottliebe on the jetty on one of those golden days has pride of place on my ‘table of the dead’, in the company of all those others who went before me, people who enriched my life and whom I do not want to forget."

Text

English translation: William Connor