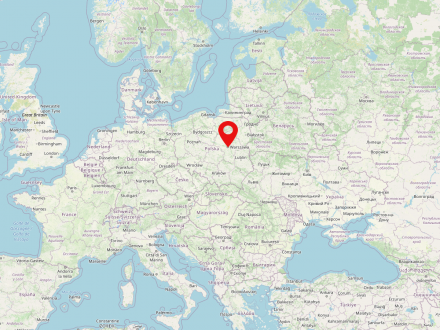

Warsaw is the capital of Poland and also the largest city in the country (population in 2022: 1,861,975). It is located in the Mazovian Voivodeship on Poland's longest river, the Vistula. Warsaw first became the capital of the Polish-Lithuanian noble republic at the end of the 16th century, replacing Krakow, which had previously been the Polish capital. During the partitions of Poland-Lithuania, Warsaw was occupied several times and finally became part of the Prussian province of South Prussia for eleven years. From 1807 to 1815 the city was the capital of the Duchy of Warsaw, a short-lived Napoleonic satellite state; in the annexation of the Kingdom of Poland under Russian suzerainty (the so-called Congress Poland). It was not until the establishment of the Second Polish Republic after the end of World War I that Warsaw was again the capital of an independent Polish state.

At the beginning of World War II, Warsaw was conquered and occupied by the Wehrmacht only after intense fighting and a siege lasting several weeks. Even then, a five-digit number of inhabitants were killed and parts of the city, known not least for its numerous baroque palaces and parks, were already severely damaged. In the course of the subsequent oppression, persecution and murder of the Polish and Jewish population, by far the largest Jewish ghetto under German occupation was established in the form of the Warsaw Ghetto, which served as a collection camp for several hundred thousand people from the city, the surrounding area and even occupied foreign countries, and was also the starting point for deportation to labor and extermination camps.

As a result of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising from April 18, 1943 and its suppression in early May 1943, the ghetto area was systematically destroyed and its last inhabitants deported and murdered. This was followed in the summer of 1944 by the Warsaw Uprising against the German occupation, which lasted two months and resulted in the deaths of almost two hundred thousand Poles, and after its suppression the rest of Warsaw was also systematically destroyed by German units.

In the post-war period, many historic buildings and downtown areas, including the Warsaw Royal Castle and the Old Town, were rebuilt - a process that continues to this day.

He found all this in

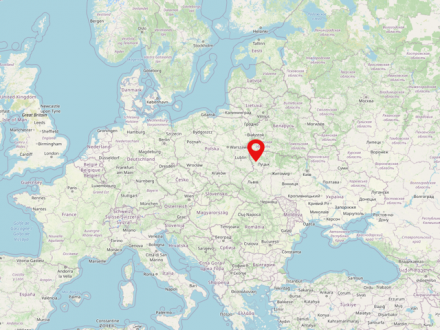

The historical landscape of Volhynia is located in northwestern Ukraine on the border with Poland and Belarus. Already in the late Middle Ages the region fell to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and from 1569 on belonged to the united Polish-Lithuanian noble republic for more than two centuries. After the partitions of Poland-Lithuania at the end of the 18th century, the region came under the Russian Empire and became the name of the Volhynia Governorate, which lasted until the early 20th century. The Russian period also saw the immigration of German-speaking population (the so-called Volhyniendeutsche), which peaked in the second half of the 19th century. After the First World War Volhynia was divided between Poland and the Ukrainian Soviet Republic, from 1939, as a result of the Hitler-Stalin Pact, completely Soviet and already in 1941 occupied by the Wehrmacht. Under German occupation there was systematic persecution and murder of the Jewish population as well as other parts of the population.

After World War II, Volhynia again belonged to the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic and since 1992 to Ukraine. The landscape gives its name to the present-day Ukrainian oblast with its capital Luzk (ukr. Луцьк), which is not exactly congruent.

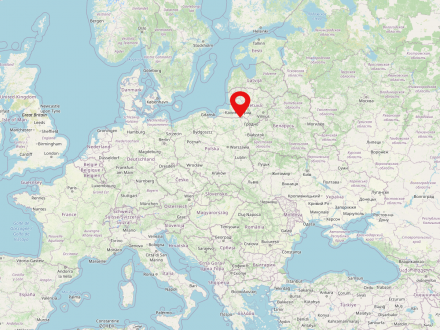

The village of Sztynort is located in the north of the Masurian Lake District on the Jez Peninsula between Jezioro Mamry, Jezioro Dargin and Jezioro Dobskie. Until 1928 the village was called Groß Steinort, then Steinort.

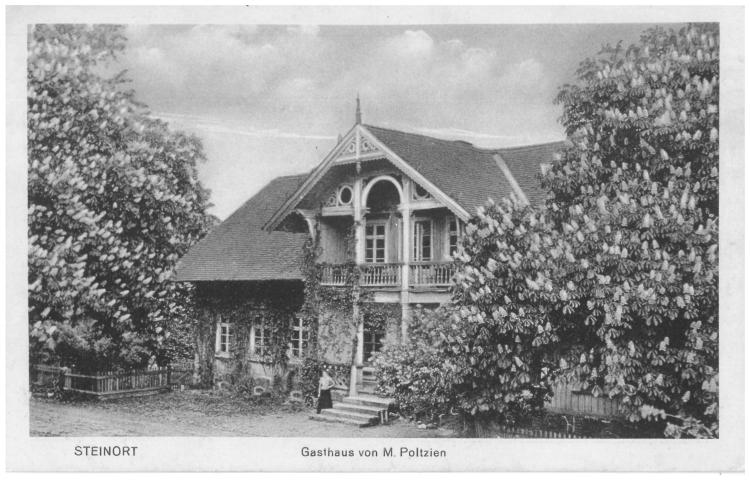

In the spring of 2005, Alexander Potocki visited the lodge with his wife. It was pouring with rain that day. Completely soaked, they stood in front of the building. It was a ruin! The right wing had collapsed, and inside there was a pile of garbage several meters high. "We went on to the castle," recalls Potocki. He speaks German without an accent. "Making our way through the overgrown grounds and back to the hunting lodge." By now the sun was out, "typical Masuria weather – changing from one minute to the next."

Suddenly Dorota turned to him and said, "Look, if you’d like to, you should give it a go." The phrase has gone down in family legend, as has Alexander's reply, "I had to show her that I was up to it!"

The Romincka Forest (also: Romincka Heath) is an extensive forest and heathland area stretching along the Polish-Russian border in the southeast of Russia's Kaliningrad Oblast and the northeast of Poland's Warmia-Masuria Voivodeship. Before 1945, the area was part of the Prussian province of East Prussia and known as a Royal Prussian hunting ground. Emperor Wilhelm II (1859-1941) had a wooden hunting lodge built here starting in 1891, which was merged after his death with the nearby Reichsjägerhof Rominten, built by the National Socialists under Hermann Göring (1893-1946), and expanded to include bunkers and other infrastructure. Göring also used the Reichsjägerhof and the military facilities as his personal headquarters and the representative buildings, including the hunt itself, for propagandistic self-dramatization.

In 2007 the restaurant and pension opened to the public. Soon the for-mer hunting lodge was attracting Polish city dwellers and travelers from Germany who were looking for a quiet rural getaway. Among their guests were many former East Prussians and their descendants.

In the entrance hangs a historical photograph of the building, showing it in its former glory, framed by blossoming chestnut trees.

In Poland, every child knows the name Potocki – one of the families of the high nobility that made history for six hundred years. An elaborately painted family tree tells of their connections with German and English noble houses. "My great-great-great-grandmother was a Dönhoff." But Potocki himself chooses not to use the title “Count”.

Anyone who enters the house finds themselves unexpectedly in a small museum. Ancestral pictures, hunting trophies, coats of arms from palaces that no longer exist. "The Potocki Palace in Warsaw was burned down by the German Wehrmacht in 1944." The Potocki family shares these fragments of a vanished world with their guests.

Kwitajny is a village in the Polish voivodeship Warmia-Masuria. The first documented mention of "Groß und Klein Quittainen" dates back to 1431.

"Why not here, in Gałkowo?" And perhaps not a memorial that focuses on the tragedies of nationalism, fascism, war and expulsion, but instead a "salon" where visitors are tempted to linger, read, meet each other.

Kosewo ist ein Dorf am Jezioro Probarskie (Probergsee) in der polnischen Woiwodschaft Ermland-Masuren, das 1546 als „Kossewen“ gegründet wurde. Von 1938 bis 1945 hieß es Rechenberg (Ostpr.) 2011 hatte Kosewo knapp über 400 Einwohner:innen.

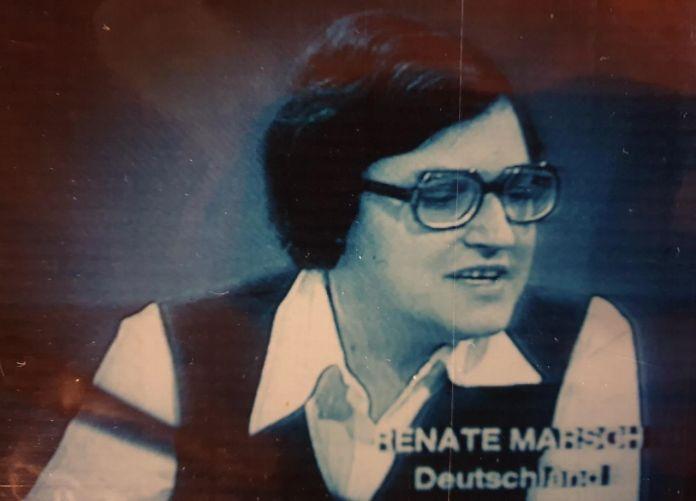

Visitors here can gain a deep understanding of the role she played in Germany's new Ostpolitik. How she said goodbye to her beloved homeland and demonstrated to other expellees and to all Germans that renunciation is necessary and reconciliation possible. Her famous sentence "Perhaps this is the highest degree of love: to love without possessing" is the motto of the Salon.

In the summer of our meeting she is 85 years old. Her eyesight has weakened and she tires quickly. For a while yet, she will carry on the legacy of Marion Dönhoff. Who will go on to tell her story?2

In Warsaw, she met Władysław Potocki, who was from a noble family, and started a family with him. The two, it is said, were bound by a com-mon trauma – her father was shot by Russians in 1945, while his father had been a prisoner in several German concentration camps.

Recently, a nephew of hers, Wolfang Crasemann, inspired by a visit to Gałkowo, created a first biographical sketch for the family. Here is a passage about her exciting life as a correspondent in the 1980s. Her son Alexander (born in 1972) still remembers: "I didn't need adventure stories as a child, I experienced them live."

Gałkowo is in many ways the intersection of German-Polish history(s). What better fate could have befallen the Lehndorff hunting lodge?

According to his definition, the hunting lodge is now a place with "a tourist future and a historical background”.