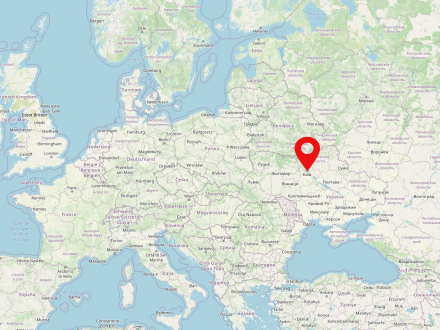

Kiev is located on the Dnieper River and has been the capital of Ukraine since 1991. According to the oldest Russian chronicle, the Nestor Chronicle, Kiev was first mentioned in 862. It was the main settlement of Kievan Rus' until 1362, when it fell to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, becoming part of the Polish-Lithuanian noble republic in 1569. In 1667, after the uprising under Cossack leader Bogdan Chmel'nyc'kyj and the ensuing Polish-Russian War, Kiev became part of Russia. In 1917 Kiev became the capital of the Ukrainian People's Republic, in 1918 of the Ukrainian National Republic, and in 1934 of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic.

Kiev was also called the "Mother of all Russian Cities", "Jerusalem of the East", "Capital of the Golden Domes" and "Heart of Ukraine".

Kiev is heavily contested in the Russian-Ukrainian war.

Due to the war in Ukraine, it is possible that this information is no longer up to date.

One of them was the Maidan Museum, the idea of which arose during the protests as a grassroots initiative of committed cultural activists, including Vasyl Rozhko, an official of the Ministry of Culture; Igor Poshyvaylo, an ethnologist associated with the Ivan Honchar Museum; and Timur Bobrovsky and Kateryna Chuyeva, both archaeologists involved in cultural heritage preservation projects.

In the autumn of 2014, “Maidan Museum” (Muzeǐ Maǐdanu) joined another grassroots initiative known as the “Museum of Liberty” (Muzeǐ Svobody), led by Aleksandra Baklanova. The activity of this new group focused primarily on collecting and protecting artifacts and testimonies related to the Revolution of Dignity, as well as developing a vision for the future museum. The first exhibition organized by a joined initiative in October 2014 took a non-traditional format that defined the museum concept.

The exhibition consisted of three independent parts: first, the traditional museum exhibition named “Freedom” (Svoboda); second, a complete program of events, including screening of films, meetings with participants of events, and lectures; and third, a unique space for visitor interaction.

The space was designed to create an opportunity for everyone to reflect on the experience of the last few months in their own way, to share their ideas about what freedom is and what the future museum should look like. As Vasyl Rozhko, who became the chairman of the official working group of the Maidan Museum, emphasized, “Muzeǐ Maǐdanu/Muzeǐ Svobody is not a traditional museum. In addition to collecting exhibits, it should become a kind of laboratory to understand the unique features of civil society in Ukraine. Combining two initiatives – the Museum of Liberty and the Maidan Museum – gives us the opportunity to realize the dream of a unique museum by creating it together with the community”1 .

Founded in 1662 as a fortress with three villages, the settlement was then called Stanisławów. Already in the following year, the town was granted the town charter of Magdeburg. The town belonged to Poland-Lithuania for a time, and later as "Stanislau" to the Habsburg Monarchy. From 1917 to 1920 it was part of the West Ukrainian People's Republic, of which Stanislau became the capital for a few months in 1919, before it briefly became part of Poland, then the Ukrainian SSR and thus the Soviet Union - since its disintegration in 1991 it has belonged to Ukraine.

The history of Stanislau/Iwano-Frankiwsk is multi-ethnic and characterised by Polish, Ruthenian/Ukrainian, Armenian, Jewish and German population groups. In 1962, the city was named after the writer and historian Ivan Franko. The university town is considered a centre of Ukrainian literature.

In 2015, Ivano-Frankivsk had almost 230,000 inhabitants.

Due to the war in Ukraine, it is possible that this information is no longer up to date.

Local volunteers and artists, who were free to express their artistic visions related to the Revolution of Dignity, actively participated in creating the interior of this small museum. Family members of the fallen, as well as their friends and living protesters, joined the creation of the museum by donating artifacts such as personal belongings of those killed, as well as helmets, shields, and weapons used during the protests.

The result was an unprecedented democratic space that was open to the ideas and creativity of the people involved. In turn, in

The area of Dnipro has been settled since prehistory. In 1635, not far from the present-day city, the fortress of Kodak was built by Poland, which was razed by Russians in 1711. In 1776, Ekaterinoslav was founded in its place as the capital of the "New Russia" governorate, moved to Dnipro's present location in 1787 due to flooding. In the course of its history, the city belonged to the Russian Empire, the Ukrainian People's Republic, the short-lived Donetsk-Kryvy Ryh Republic, the Ukrainian SSR and, after the disintegration of the Soviet Union, to present-day Ukraine. It bore various names throughout its history, such as Ekaterinoslav, Novorossiysk, Sitzheslav and Dnipropetrovsk. A "closed city" in the Soviet Union because of its arms industry, Dnipro is now an important industrial and financial centre.

Dnipro had almost 987,000 inhabitants in 2015.

Due to the war in Ukraine, it is possible that this information is no longer up to date.

The museum’s mission is to create a safe space where meanings are negotiated concerning the recent history of Ukraine, as well as the vision of future Ukraine and its place in the world. As in the case of the museum in Ivano Frankivsk and Dnipro, participants and witnesses of the events became the primary sources of information. They in turn helped shape the public narrative about the history of Ukraine.

In this sense, new museums are model “contact zones”3 , where a story about the community is co-created, but also - where the community is created by working together on trauma and memory. The assumptions the new museum creators go far beyond the collection of historical items, and even - beyond the collection of memories and stories.

Such meetings offer more involvement, allow participants to get first-hand information, establish interaction that enables important questions, and finally confront participants with the question of what they would do in a similar situation. Fighting for one’s own country – as Poshivaylo emphasizes – is a free choice. The presentation of the figures of people who consciously made this choice could be an important and effective element in shaping young Ukrainians’ civic and patriotic attitudes.

Other types of activity include workshops for children and young people; books and comics promotions; movie screenings; poetry and song evenings; photographic, poster and painting exhibitions; meetings with artists; lectures, supportive actions in solidarity with war prisoners; and more intimate activities, such as birthday celebrations of dead heroes and writing letters to soldiers fighting on the front.

The Museum of the Revolution of Dignity in Kyjiw aims to be “an intellectual and creative hub, the heart of initiatives of all kinds for inclusive reflection on the past and consolidated creation of the future”. Also, new regional museums act as an umbrella for different kinds of social initiatives, as they become centers of civic activity, integrating local communities. As Vadim Yakushenko, the head of the ATO Museum in Dnipro, highlighted, the new Ukrainian museums are “a reflection of the present, witnessing the birth of a healthy and free society”.

The Kyjiw museum was well prepared for this task, having taken care of international contacts and developing its paths of dealing with crises in the past few years. As part of the "Heritage Emergency Response Initiative" established in early March, a few days after the start of military operations by Russia, the Museum helps to disseminate materials on saving cultural heritage, and organizes workshops and webinars for cultural workers.

The museum director, Igor Poshyvailo, is actively involved in coordinating cooperation between Ukrainian museums and cultural institutions, and such powerful actors as UNESCO, ICOM-Disaster Resilient Museums and ICCROM. Museum employees also participate in expeditions in which losses are assessed, the surviving materials are secured, and the certificates of Russian crimes against cultural heritage are collected.

In today's wartime conditions, museum workers call themselves “soldiers of the cultural front”. In fact, preserving the legacy of the democratic revolution that changed their country depends largely on their struggle and perseverance.