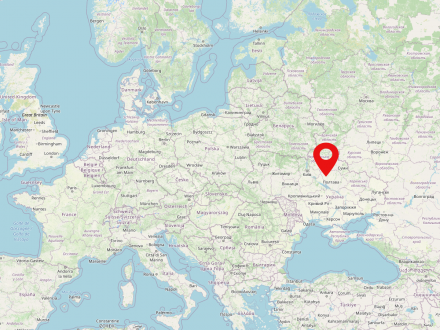

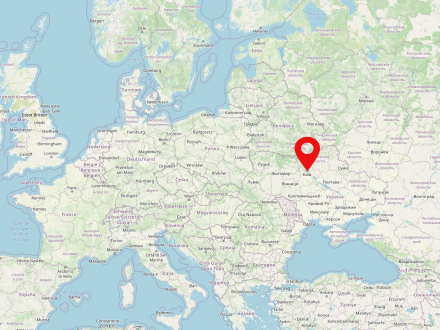

Ukraine is a country in eastern Europe inhabited by about 42 million people. Kiev is the capital and also the greatest city of Ukraine. The country has been independent since 1991. The Dnieper River is the longest river in Ukraine.

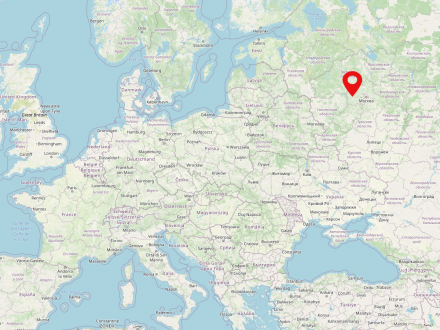

The Russian Federation is the largest territorial state in the world and is inhabited by about 145 million people. The capital and largest city is Moscow, with about 11.5 million inhabitants, followed by St. Petersburg with more than 5.3 million inhabitants. The majority of the population lives in the European part of Russia, which is much more densely populated than the Asian part.

Since 1992, the Russian Federation has been the successor state to the Russian Soviet Republic (Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic, RSFSR), by far the largest constituent state of the former Soviet Union. It is also the legal successor of the Soviet Union in the sense of international law.

Kiev is located on the Dnieper River and has been the capital of Ukraine since 1991. According to the oldest Russian chronicle, the Nestor Chronicle, Kiev was first mentioned in 862. It was the main settlement of Kievan Rus' until 1362, when it fell to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, becoming part of the Polish-Lithuanian noble republic in 1569. In 1667, after the uprising under Cossack leader Bogdan Chmel'nyc'kyj and the ensuing Polish-Russian War, Kiev became part of Russia. In 1917 Kiev became the capital of the Ukrainian People's Republic, in 1918 of the Ukrainian National Republic, and in 1934 of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic.

Kiev was also called the "Mother of all Russian Cities", "Jerusalem of the East", "Capital of the Golden Domes" and "Heart of Ukraine".

Kiev is heavily contested in the Russian-Ukrainian war.

Due to the war in Ukraine, it is possible that this information is no longer up to date.

Irpin (population 2021: 65,167) is located on the same-named river in the Ukrainian oblast of Kyiv, in the Buča district. The town, which was only established at the beginning of the 20th century, was granted city rights in 1956. Before the Russian attack on Ukraine in 2022, Irpin was considered an emerging suburb of Kiìv. In February-March 2022, Irpin and the neighboring towns of Hostomelʹ and Buča were affected by fierce fighting and Russian massacres of the civilian population, with over 400 people killed.

The city of Buča (population 2021: 37,321) is located in the Ukrainian oblast of Kyiv, on the Buča and Rokač rivers. Today's town originated as a railroad settlement, which developed into a spa town towards the end of the 19th century. Buča established itself as a popular suburb of Kiìv even before it was granted city rights in 2007.

In the initial phase of the Russian military aggression against Ukraine in February-March 2022, Buča and the neighboring towns of Irpin and Hostomel were affected by fierce fighting and Russian massacres of the civilian population with over 400 people killed.

The urban settlement of Hostomel (population 2021: 18,466) is located in the Ukrainian oblast of Kyiv, in the Buča district. Hostomelʹ held city rights from 1619 to 1938. Before the Russian attack on Ukraine in 2022, the town was considered an emerging suburb of Kyiv. In February-March 2022, Hostomel and the neighboring towns of Irpin and Buča were affected by fierce fighting and Russian massacres of the civilian population, with over 400 people killed.

Borodyanka (population 2021: 12,832) is located in the Ukrainian oblast of Kyiv. The settlement, which has been known since the 11th century, was only granted the status of an urban-type settlement in 1954. The multi-storey buildings in the village were largely destroyed in night-time bombardments in 2022 during the early phase of the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

The photos from Mariupol illustrate the scale of the humanitarian catastrophe in a city without a permanent supply of water, electricity, and heat. Considering the scale of the damage—it is estimated that up to 80 percent of the buildings in the city were affected—the comparisons to Warsaw in 1944 and Aleppo in 2016 made in the description seem justified. Last but not least, the exhibition includes a request for recognition of Russia’s actions as an act of genocide against the Ukrainian nation and humanitarian aid for the imprisoned city from the Mariupol City Council.