In East Germany, the Copernicus anniversary was marked by a range of ceremonies and receptions. The aim was to highlight positive relations between Germany and Poland, with Copernicus being presented as a pioneer for the socialist state’s worldview.

Text

While, in West Germany, the 1973 Copernicus celebrations sought to bridge the gap between various efforts to present a modern view of Copernicus on the one hand and to reveal the special role that Copernicus played as a representative of the former “deutschen Osten” (“German east”, referring to German-speaking areas in Eastern Europe) on the other, in East Germany this issue was clarified at the political level. It was therefore important that the legitimacy of East Germany’s socialist sister state, Poland, was not brought into question through any references to the Germanic history of the land of Prussia. As such, Copernicus was consistently presented as a great Polish astronomer and polymath. The Polish version of his name, Mikołaj Kopernik, was even used on occasion. At a celebratory meeting of the Academy of Sciences, Herbert Weiz, the deputy chair of the East German Council of Ministers, described the anniversary as being celebrated “together with the Polish People’s Republic and all of progressive humanity”1 – a reference to the socialist states.

Text

This short quote from Weiz, who served as East German Minister for Science and Technology from 1974 until German reunification in 1989, points both to the content of the celebrations and their ideological nature. The celebrations in West Germany were arranged by different organizations, including the “East German” regional associations; but, in East Germany, the program of events to mark the anniversary of Copernicus’ birth appeared to be lacking the independent involvement of civilian groups and was instead heavily influenced by the state. Like its neighbor, East Germany also had a committee with a remit to organize the anniversary celebrations. But unlike the West German equivalent, this was simply a committee from the Academy of Sciences, rather than an amalgamation of different organizations. As the “revolutionary work of Copernicus [...] was to be made accessible to the workers and, above all, young people”,2 there were some events designed for the wider public. These included an exhibition at Berlin State Library and a radio series broadcast in 1972 by Radio DDR II in conjunction with the educational organization Urania. Aside from this, the program was dominated by official events, such as ceremonies at universities and receptions for Polish delegates.

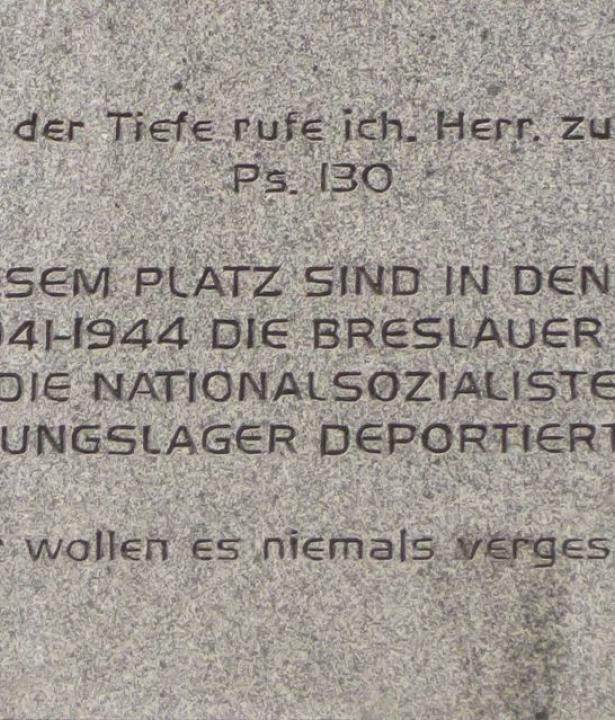

In May 1973, a German-Polish work team in the Berlin Oberspree cable factory was given the honorary name “Kopernikus”. Foto von Ulrich Kohls, Bundesarchiv / photo by Ulrich Kohls, German Federal Archive, image 183-M0508-0038, CC BY-SA 3.0

In May 1973, a German-Polish work team in the Berlin Oberspree cable factory was given the honorary name “Kopernikus”. Foto von Ulrich Kohls, Bundesarchiv / photo by Ulrich Kohls, German Federal Archive, image 183-M0508-0038, CC BY-SA 3.0

Text

The published commemorative speeches reveal that the discussions about Copernicus were framed by an attempt to construe the astronomer as part of the “progressive traditions” that had been heavily drawn upon in East Germany and other Eastern Bloc countries as a historical legitimation for socialism since the 1970s. One example of this can be seen in a quote by Friedrich Engels, which was used in many speeches and articles from the time. Engels named Copernicus as one of the “giants of thought, passion, and character, of versatility and learning”3 who had inspired progressive moments in world history. It was often argued that Copernicus was a precursor to Engels’ own worldview. Thus, for example, in a lecture at Martin Luther University in Halle-Wittenberg, medieval historian Hans-Joachim Bartmuß said: “This Copernican worldview inevitably led in its final philosophical consequence to the materialistic conception [...] whose historical climax is the worldview of the working class, the socialist society.”44 He accused the “bourgeois” science of western countries of minimizing the revolutionary act of Copernicus. He called Copernicus “a real subversive”5 and someone who “opened the door to all Earthly revolutions near and far, both in his lifetime and subsequently.”6 By contrast, the “socialist national cultures” could claim to have “faithfully preserved this Copernican legacy.”7

Text

Bartmuß believed that the revolutionary spirit of Copernicus was manifested in the fact that he “destroyed the fanciful and despotic dominium mundi idea of the Middle Ages for good”8 and, through his astronomical research, “even made it possible to enter heaven through the exercise of common sense.”9 In other words, he removed the Catholic Church’s interpretative authority. This “significance of Copernicus’ teachings for materialistic philosophy and for an atheism grounded in science”10 was also noted by philosopher Helmut Mielke. However, the fact that Copernicus was in the service of the Church and that there is no evidence for his alleged criticism of the Church’s authority stands in contradiction to the view that he was a supposed unifier of a speculative, medieval Christian worldview. Mielke explains this contradiction through an oft-cited distinction in Marxist-Leninist theory between a merely secondary superficial structure and the underlying historical principles which should be seen as the primary forces: “Although Copernicus was himself a canon, and therefore a member of the high clergy who shared in the feudal and clerical privileges, objectively speaking, his work served the interests of the rising middle class.”11

Text

While by the 1970s there were already various collaborations between Polish scientists and colleagues from West Germany and the USA, there is little evidence of collaborations between East and West German colleagues on the subject of Copernicus. The science community in East Germany rejected the emerging interpretation in West Germany of Copernicus as a figure from European history who transcends national borders: It was argued that this should be understood as a symptom of a “reactionary European ideology”12 with which “bourgeois” science sought to repel the historical and materialistic interpretations developed in East Germany.

Text

English translation: LEaF Translations