Casting shadows

Text

Nicolaus Copernicus mentioned three astronomical instruments in his book "De Revolutionibus". The first is a sundial, which was made from basic materials. According to American astronomy historian Prof. Owen Gingerich, Copernicus used the sundial to calculate the date of the equinox (when day and night are of the same length): To do this, [...] he had to mark the highest and lowest positions of the noon shadows during the year, and bisect the angle between them. When the noon shadow fell on the bisection point, that was the time of the equinox." (Owen Gingerich/James Mac Lachlan: Nicolaus Copernicus: Making The Earth A Planet. Oxford/New York 2005, S. 83)

Modern sundial on the library building in Frombork (formerly Frauenburg) cathedral district. Aleksandra39, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0

Modern sundial on the library building in Frombork (formerly Frauenburg) cathedral district. Aleksandra39, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0

To the zenith

Text

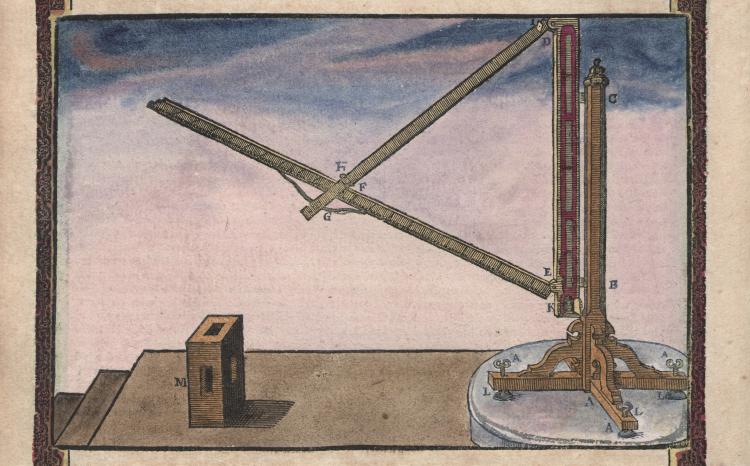

The second instrument mentioned by Copernicus is the triquetrum. He described the construction of the “Parallactic instrument”, as he called it, in the fourth book of De Revolutionibus. It consisted of three rods, two of which could be pivoted on hinges, and a vertical post. The upper rod featured sights to look at a star, while the lower rod included a scale to measure the position of the upper rod. The observer could then use a trigonometry table to calculate the zenith distance, i.e. the angle between the position of the star or planet and the vertical point. The triquetrum was not very accurate, however, not least because the wooden posts were prone to becoming warped.

Illustration of a triquetrum in Tycho Brahe’s Astronomiae Instauratae Mechanica, Wandesburg, 1598. Sächsische Landesbibliothek – Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek / Saxon State and University Library Dresden, S.B.14, CC0 1.0

Illustration of a triquetrum in Tycho Brahe’s Astronomiae Instauratae Mechanica, Wandesburg, 1598. Sächsische Landesbibliothek – Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek / Saxon State and University Library Dresden, S.B.14, CC0 1.0

Set up and read

Text

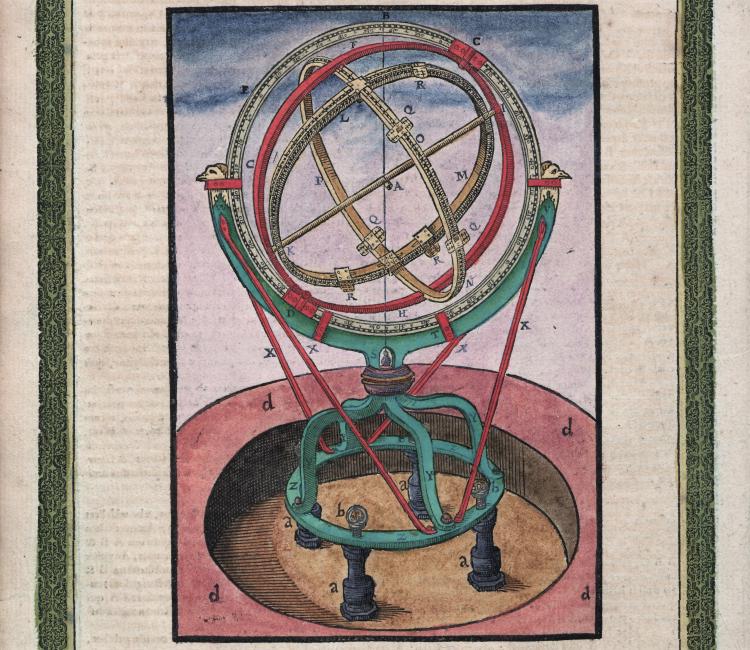

The third and most complex instrument referenced by Copernicus was the armillary sphere. This is a construction of intertwined rings. When positioned correctly at different celestial observations (such as the apparent path of the Sun to the Earth), coordinates for stars or planets could be read from the mobile sights. Copernicus’ observations suggest that it is highly likely he owned and used an armillary sphere. None of his astronomical instruments have survived, however.

Illustration of an armillary sphere in Tycho Brahe’s Astronomiae Instauratae Mechanica, Wandesburg, 1598. Sächsische Landesbibliothek – Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek / Saxon State and University Library Dresden, S.B.14, CC0 1.0

Illustration of an armillary sphere in Tycho Brahe’s Astronomiae Instauratae Mechanica, Wandesburg, 1598. Sächsische Landesbibliothek – Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek / Saxon State and University Library Dresden, S.B.14, CC0 1.0

A relic

Text

From 1516, Nicolaus Copernicus served as administrator of all the assets belonging to the Varmian cathedral chapter and spent this period at Allenstein Castle (now Olsztyn Castle). An astronomical chart has been preserved from this period in the cloister in the northern wing of the castle. It is likely that a mirror was used to reflect the light from the Sun onto this chart so its course could be charted. The seven-meter-wide chart is located above the entrance to the rooms in which Copernicus lived and worked. It is believed that he created the chart himself.

Astronomical chart in the cloister of Olsztyn Castle. Olerys, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0

Astronomical chart in the cloister of Olsztyn Castle. Olerys, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0

Observation conditions

Text

In the fifth volume of De Revolutionibus, Copernicus complained about the fact that it was almost impossible for him to observe the planet Mercury in Frauenburg (Frombork). He claimed this was because he had to live in a harsher climate than the astronomers from antiquity, owing to the haze from the Vistula River – although the river’s delta lies around 50 kilometers from Frombork. Here, Copernicus was referring to the Vistula Lagoon (Zalew Wiślany in Polish), which is where several rivers, including the Nogat – a tributary of the Vistula – meet the sea. The coastline here is definitely not an ideal location for astronomical observations.

View over Frombork port and the Vistula Lagoon. Aleksander Durkiewicz, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0

View over Frombork port and the Vistula Lagoon. Aleksander Durkiewicz, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0

Searching for clues

Text

It has been proven that Copernicus maintained a simple observatory at his canon house on the outskirts of Frauenburg’s cathedral district. The “Pavimentum” was a platform from which observations could be performed and measurements taken. The canon house was destroyed during an invasion by the Teutonic Order in 1520. Historians believe that it was located to the west of the cathedral district. Modern geophysical investigations have been undertaken in this area to search for traces of the Pavimentum, albeit without success.

Newer building on the presumed location of Copernicus’ canon house. BroviPL, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0

Newer building on the presumed location of Copernicus’ canon house. BroviPL, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0

No observatory

Text

It is sometimes presumed that Copernicus also used the tower in which he lived in the cathedral district of Frauenburg as a place from which to observe the sky. But researchers now believe that the tower’s narrow wooden gallery was not suitable for the work undertaken by astronomers back then. It is, however, highly likely that Copernicus worked on the manuscript for his main work, De Revolutionibus, in his tower apartment.

“Copernicus Tower” in Frombork. Lech Darski, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0

“Copernicus Tower” in Frombork. Lech Darski, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0

Paths to findings

Text

A painting by Jan Matejko (1838-1893), which is very famous in Poland, shows Nicolaus Copernicus in a fictional moment of revelation, effectively in a “conversation with God”, in which the actual relationships in the cosmos are revealed to him. This moment cannot actually have taken place, as the observations with the triquetrum – the wooden rods of which can be seen to the right of the painting – were just the foundations for geometric theories from which Copernicus derived his findings. Copernicus also has a telescope on his lap in this sketch. But it was nowhere to be seen on the large painting, which was finished in 1873 and now hangs in the Jagiellonian University in Cracow – and with good reason...

Jan Matejko, sketch for the painting Astronomer Copernicus, or Conversations with God, 1871. Nationalmuseum Krakau / National Museum in Cracow, MNK IX-25, CC0 1.0

Jan Matejko, sketch for the painting Astronomer Copernicus, or Conversations with God, 1871. Nationalmuseum Krakau / National Museum in Cracow, MNK IX-25, CC0 1.0

Science with simple tools

Text

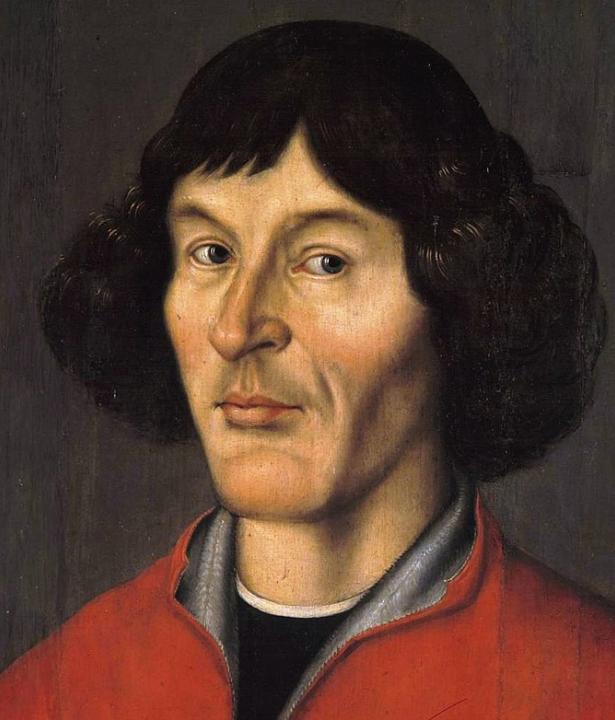

This engraving from the late 17th century shows Copernicus (second from the right) together with the Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe (1546-1601) and Claudius Ptolemy: Here, they represent the long epoch of astronomy, in which it was only possible to view the sky with your bare eyes and without any optical aids. Galileo Galilei and Johannes Hevelius (1611-1687), an astronomer from Gdansk, are shown to the left as representatives of a new era. They are both depicted with refracting telescopes, which came into circulation after 1608. Hipparchus of Nicaea is shown in the foreground as the founder of scientific astronomy.

Astronomy one century on

Text

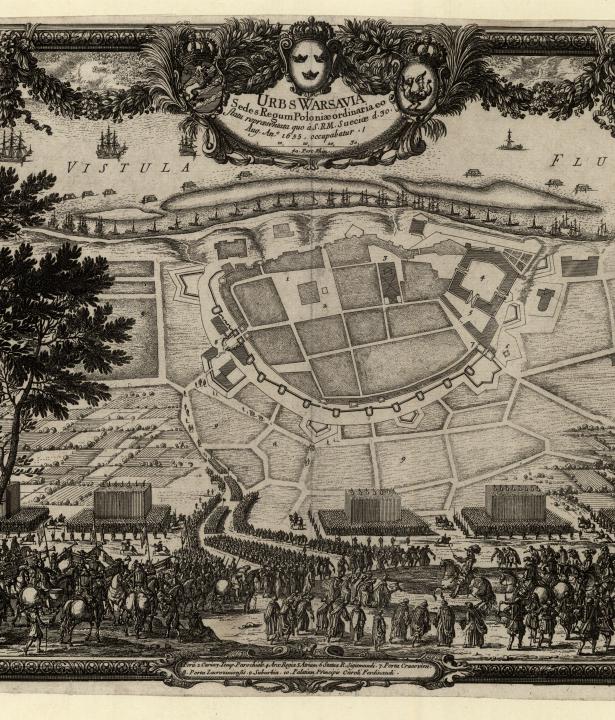

Since Tycho Brahe had made considerable refinements to the process of making observations at the end of the 16th century, astronomers worked with a wide range of often large-scale instruments. The observatory established on the Vestner Gate Bastions at Nuremberg Castle in 1678 by Georg Christoph Eimmart (1638-1705), is one example. Its location was only around 200 meters away from the former workshop of Johannes Petreius, where the first edition of Copernicus’ main work, De Revolutionibus, was printed in 1543.

Eimmart Observatory in Nuremberg, illustration from The Atlas Coelestis by Johann Gabriel Doppelmayr, Nuremberg, 1742. Universitätsbibliothek Freiburg / University Library Freiburg, J 8564,b, CC0 1.0

Eimmart Observatory in Nuremberg, illustration from The Atlas Coelestis by Johann Gabriel Doppelmayr, Nuremberg, 1742. Universitätsbibliothek Freiburg / University Library Freiburg, J 8564,b, CC0 1.0