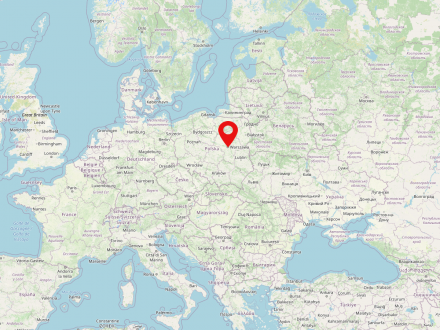

Warsaw is the capital of Poland and also the largest city in the country (population in 2022: 1,861,975). It is located in the Mazovian Voivodeship on Poland's longest river, the Vistula. Warsaw first became the capital of the Polish-Lithuanian noble republic at the end of the 16th century, replacing Krakow, which had previously been the Polish capital. During the partitions of Poland-Lithuania, Warsaw was occupied several times and finally became part of the Prussian province of South Prussia for eleven years. From 1807 to 1815 the city was the capital of the Duchy of Warsaw, a short-lived Napoleonic satellite state; in the annexation of the Kingdom of Poland under Russian suzerainty (the so-called Congress Poland). It was not until the establishment of the Second Polish Republic after the end of World War I that Warsaw was again the capital of an independent Polish state.

At the beginning of World War II, Warsaw was conquered and occupied by the Wehrmacht only after intense fighting and a siege lasting several weeks. Even then, a five-digit number of inhabitants were killed and parts of the city, known not least for its numerous baroque palaces and parks, were already severely damaged. In the course of the subsequent oppression, persecution and murder of the Polish and Jewish population, by far the largest Jewish ghetto under German occupation was established in the form of the Warsaw Ghetto, which served as a collection camp for several hundred thousand people from the city, the surrounding area and even occupied foreign countries, and was also the starting point for deportation to labor and extermination camps.

As a result of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising from April 18, 1943 and its suppression in early May 1943, the ghetto area was systematically destroyed and its last inhabitants deported and murdered. This was followed in the summer of 1944 by the Warsaw Uprising against the German occupation, which lasted two months and resulted in the deaths of almost two hundred thousand Poles, and after its suppression the rest of Warsaw was also systematically destroyed by German units.

In the post-war period, many historic buildings and downtown areas, including the Warsaw Royal Castle and the Old Town, were rebuilt - a process that continues to this day.

In this article, I briefly outline the fascinating process of Warsaw's architectural and urban development and its maturation into a capital, as documented by maps and plans from the 17th and 18th centuries. The aim of compiling cartographic sources and attempting to reconstruct the landscape of the city in the 18th century is, on the one hand, to draw attention to the phenomenon of the so-called Warsaw escarpment Warsaw escarpment The Warsaw escarpment is the western edge of the Vistula River valley in Warsaw. The escarpment is pierced by small natural gorges, but there are also artificial breakthroughs. The escarpment enabled Warsaw to dispense with a large eastern defensive fortification. Unfortunately, nothing is known about the exact origin of the escarpment. , and on the other, to acknowledge the undeniable role of the artistic and architectural patronage patronage A patron (also patronage, female patron) is a financier, an institution, a local authority or a person who supports the implementation of a project with money or money's worth. No direct service in return is required. The term patron is derived from the Etruscan and Roman Gaius Cilnius Maecenas, who sponsored poets such as Virgil, Horace and Properz in Augustan times. Patrons can support a variety of fields in the arts, or university graduates, as well as science. of the Wettins Wettins The House of Wettin is one of the oldest German noble families. In the Middle Ages, the house mainly represented the Margraves of Saxony, the Landgraves of Thuringia, as well as the Dukes and Electors of Saxony. In 1485, with the division of Leipzig, the house split into an older (Ernestine) and a newer (Albertine) line. The Ernestines ruled for the most part over what is now Thuringia, the Albertines over what is now Saxony. Due to the confessional conflicts in the 16th and 17th centuries, the electoral dignity passed from the Ernestine to the Albertine line (1548). Like the Ernestine line, the Albertine line was Protestant but more loyal to the emperor than its Ernestine relatives. The present Belgian royal house descends from the Ernestine line of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. , whose merits in this respect have long been devalued or wrongly attributed to their successor.

The topographical determinant of Warsaw's urban development in the 18th century was not only an engineering and construction challenge, but also an expression of the social and mental changes triggered by the clash of various Saxon cultures and the Sarmatian Polish-Lithuanian kingdom. This particular combination of natural and cultural factors, as well as the historical turmoil in Europe at the time, led to the emergence of a unique artistic movement known as Dresden Baroque Dresden Baroque The Dresden Baroque is a specific form of the Baroque under the Saxon Elector and later Polish King (1670-1733) and his son Friedrich August II (1696-1763). In addition to French models, Italian influences in particular influenced the formal language of the royal city, which spread to the whole of Saxony and eventually to Poland, especially Warsaw. At the beginning of his reign from 1694, August concentrated on representative festivities in which he himself played the leading role. However, his first decades were primarily marked by the very costly acquisition of the Polish royal crown in 1697 and the even more costly Great Northern War from 1700. As a result, his first building, the Tauschenberg Palace, was not erected until 1705-1708. Also of considerable fame to this day is the Grand Mogul's court, this work of art was purchased by August as expected and paid off for years to come. The king endeavoured to reform the administrative, legal, fiscal and military systems with the aim of enforcing centralist principles of rule, which were also expressed in building regulations. For example, rules were laid down regarding the exclusive use of stone, the number of storeys and the colour of the plaster. The construction of the Dresden Zwinger by Matthäus Daniel Pöppelmann in 1711, which was influenced by Italy and became a representative of the High Baroque, is outstanding. Eight years later, Pöppelmann added an opera house to the Zwinger. With a time lag compared to Italy and France, the Augustan Baroque emerged in its own field of tension. The moderate architectural forms of the north met with the Counter-Reformation art of the south. August's conversion to Catholicism had prepared the ground for the Baroque as an art of the Counter-Reformation in Saxony, as it rarely came to splendid fruition in northern, Protestant-influenced regions (with the exception of the Prussian palaces of Frederick II). The Seven Years' War of 1756 brought the heyday of the Augustan Age to an abrupt end. During the Second World War, Dresden's historic baroque city was destroyed. However, countless partially destroyed buildings were removed in the course of reconstruction and fell victim to planned demolition. Important ruins were rebuilt despite protests, so that today the Frauenkirche and the Dresden Residenzschloss can be admired again. , sometimes also referred to as Warsaw-Dresden Baroque. 3

The Warsaw and suburban residences, which were built from scratch or modernized by the magnates, developed into independent centers of art patronage in the years 1697-1763, playing an equally important role in the formation of the city as the royal court.

The topographical phenomenon of Warsaw, which is of almost unrivalled significance in Europe, is characterized, as mentioned above, by the coexistence of the unique local topography and the river. The high, steep slopes that rise above the Vistula, the ravines that cut through them, the valleys of smaller rivers, and underground springs made it possible for a fortified settlement to be built here in the Middle Ages. The riverbank, commonly called the Warsaw escarpment, is a geomorphological formation, the origin of which is still unexplained. In the otherwise flat Mazovia region, such a dominant landscape offered unique opportunities, but also urban challenges. Rising to 108m above sea level at its highest point, it offered unobstructed, far-reaching views on the one hand, but on the other hand it restricted the spatial development of the city for many years, with the settlement mainly concentrated on the crest of the escarpment.

The first hundred years of the formation of the capital, which began in 1592, were a difficult time, marked above all by the devastation of the "Swedish deluge" "Swedish deluge" The "Swedish Flood" consisted of at least two conflicts: the Russian-Polish War from 1654 to 1667 and the Polish-Swedish War from 1655 to 1660/61. The Russo-Polish War between 1654 and 1667 was one of the many Polish-Russian wars that lasted into the 20th century. It began because the Russian Tsarist Empire allowed the Ukrainian Cossacks to rebel against what they perceived as Polish supremacy. The main conflict was over the rule of Ruthenia. The war ended in a stalemate between Poland-Lithuania and the Russian Tsardom, partly due to the intervention of Sweden. The Tsarist Empire was able to extend its territory to the Dnieper through the war over eastern Ukraine. The Second Polish-Swedish War, also called the Second Northern War or the Little Northern War, war between Poland-Lithuania and Sweden and their allies for supremacy in the Baltic. Almost all of Poland-Lithuania's neighbouring states were involved in the war, including Russia, which fought its disputes with Poland-Lithuania, which were closely connected to the Second Northern War, as part of the Russo-Polish War of 1654-1667. In Poland, the period of the war with Sweden, but often also the entirety of the military conflicts of the 1650s and 1660s, is referred to as the "(Bloody) Deluge" or the "Swedish Deluge" (Polish: Potop Szwedzki), because the kingdom experienced a veritable deluge of invasions by foreign armies at that time. Danes, Norwegians and Swedes occasionally use the term Karl Gustav Wars, which refers to the Swedish King Karl X Gustav. The devastation of the "Swedish Deluge" is similar to that of the 30 Years War in the territory of the Holy Roman Empire. . This invasion from the north left Warsaw in a very bad condition. The cartographic document illustrating the central part of the city, which was known as Old Warsaw at the time of the Swedish invasion, is the so-called Dahlberg Plan, with a supplementary panorama of the city from the left bank of the Vistula. The latter gives a more complete picture of the appearance of the city, which at that time was a captivating sight with its multitude of tall towers, the splendid palaces of the Kazanowski family, the abovementioned Koniecpolski Palace Koniecpolski Palace The Koniecpolski Palace was built in the 17th century. The city palace in the Krakow suburb on the Royal Road in Warsaw was built between 1643 and 1645 by Constantino Tencalla for the hetman Stanisław Koniecpolski and his family. Various changes of ownership and renovations followed, including the construction of a theatre in the main building. In the middle of the 19th century, Chrystian Piotr Aigner rebuilt the palace in the classicist style and extended the side wings. Likewise, Aigner gave the garden front a neo-Renaissance shape. On 24 February 1818, the then seven-year-old Frédéric Chopin played his first public concert here and was henceforth referred to as the "Polish Mozart". The monumental building, consisting of a main body with two side wings, survived the Second World War almost intact. In the entrance area to the spacious inner courtyard is a replica of the Józef Antoni Poniatowski monument, the nephew of the last King of Poland Stanislaw August Poniatowski (abdicated 1795). As a venue for historic political meetings, the Warsaw Presidential Palace achieved worldwide fame: in 1955, the Warsaw Treaty was signed here. The treaty that addressed German-Polish relations and was to regulate their future development was also drawn up there. Since 1994, it has been the privilege of the Polish President to reside in the neoclassical palace. , and the so-called Villa Regia of the king. Meanwhile, the most impressive and eye-catching example of garden art, which was developing in Warsaw at that time, could be found at the palace established by the Grand Crown Prince Stanisław Koniecpolski. The accompanying ornamental garden was not as close to the city as some others, but it was remarkable and innovative in the way it took advantage of the topography, gently descending the wide slope above the Vistula to the riverbank below.

All the other gardens, including those at Ujazdów and at Villa Regia on Krakowskie Przedmieście Street, afforded no view of the Vistula valley due to the mass of palaces that stood in the way.

Towards the end of the reign of Jan III Sobieski (d. 1696) many magnificent residences were built scattered around the city. The royal estate in Wilanów, which has been compared to the Grand Trianon Grand Trianon The Grand Trianon is a pleasure palace in the palace gardens of Versailles near Paris. As a private retreat, King Louis XIV had the Grand Trianon built according to the plans of the architect Jules Hardouin-Mansart in 1687-1688 on the site of what was then the village of Trianon. The building was designed with precious marbles and named Trianon de Marbre. It retained this name until the construction of the neighbouring Petit Trianon, which, thanks to its later owner Marie-Antoinette, achieved fame and was to leave its mark on the era. Far removed from etiquette and court ceremonial, Louis XIV withdrew to the Grand Trianon with his favourite Madame de Maintenon, as unlike Versailles, not everyone was allowed to visit there. His successors also preferred it as a place to stay, so that Napoléon too first gave the rooms to his mother and finally had the buildings, which were now over a hundred years old and in a state of disrepair, renovated for himself. This was remodelled under him in the Empire style, while other rooms still show Baroque decoration. The multi-winged building was designed as a single-storey structure and, with its large round-arched windows, conveys a spacious and generous impression. The highlight is the peristyle, a portico from which the individual sections of the building lead away. , the palace of Queen Maria Kazimiera Sobieska in Marymont, the king's hunting pavilion on the river island on the right bank of the Vistula, and Krasiński Palace are just a few of the magnificent constellation of residences and gardens that would be created by the visionary monarch, the Elector of Saxony, King August II of Poland and Lithuania.

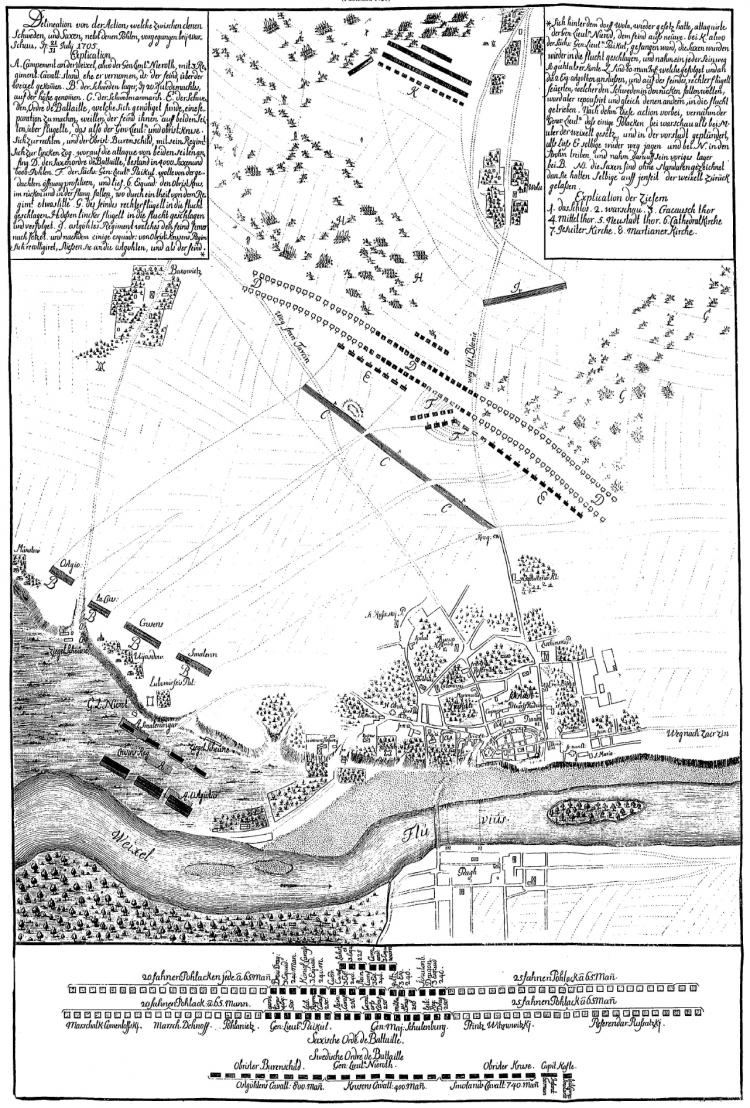

The first map to give an impression of the developments in Warsaw and Praga at the beginning of the 18th century is an illustration from the Theatrum Europeaeum, created around 1705, documenting the course of the Battle of Warsaw. It schematically shows the district known as Old Warsaw and the area adjacent to it, Krakowskie Przedmieście (Krakow Suburb), from the west. According to the map, the parts of Krakowskie Przedmieście where the ground was sloping or uneven were covered with trees, which were remnants of a former forest. At that time, pine-oak forests (Pineto-Quercetum) predominantly grew here.5

The planning and investment activity of the Royal Building Authority in Warsaw reached its peak between 1710 and 1733, as a glance at the map produced by Christoph Friedrich von Werneck in 1732 shows. Two variants of this plan were prepared for the Major General of the Crown Army, August Aleksander Czartoryski (b. 1697 - d. 1782)6, and the Court Marshal of the Crown, Franciszek Bieliński (b. 1683 - d. 1766)7, respectively. We see a complete and well-organized southern suburb of the city. The representative Krakowskie Przedmieście Street is shown as a wide thoroughfare, lined on both sides with residential buildings, temples, and spacious suburban apartments. It leads south from the Royal Castle and ends at the intersection that marks the beginning of the “Way of the Cross” (PL: Kalwaria Ujazdowska). This “Way of the Cross” (PL: Kalwaria Ujazdowska) was built in the form of an avenue lined with rows of linden trees (tilia sp.), with accompanying structures (such as small brick chapels explaining the stages of Christ's Passion, stone and grass benches for pilgrims, and Golgotha and Christ's tomb). Leading along the edge of the Warsaw escarpment to the Royal Castle in Ujazdów, it was also a representative road; its location and orientation conveyed a strong symbolic message, and it became one of two main urban axes that would determine the city’s spatial development in years to come.

Carl F. Hübner also produced two cartographic plans of the city at the turn of the 1730s and 1740s. The first9, made and published in 1733, illustrates the layout of the city at the end of Augustus the Strong's life. The map covers the area from the Royal Castle in Ujazdów through the southern and western suburbs, including the so-called Old Warsaw, to the northern suburbs where the barracks in Bielany were located. Particularly noteworthy are the two extensive gardens of August the Strong in Ujazdów and in the city center near the Royal Palace. In the depiction of Ujazdów, a royal building complex can be seen, made up of the belvedere, the Ujazdowski Palace, the building that housed the royal baths, and a zoo. The hunting ground at the foot of the escarpment, on the top of which the castle stands, was enclosed by a fan-shaped canal system, which included an almost 800-meter-long water canal designed by the king himself, executed by Burkhard Christoph von Münnich (1683-1767), and completed around 1726 by Christoph Carl d'Isebrandt. North of Ujazdów, a linear structure stands out on the map, which runs in the direction of the southern suburbs of Old Warsaw. This is the “Way of the Cross” (PL: Kalwaria Ujazdowska). It was created between 1724 and 1731 and laid the foundation for the urban development of this part of the city in the coming decades. Near the village of Solec, one can see a series of suburban dwellings directly on the riverbank, accompanied by small gardens overlooking the escarpment or the Vistula River. The second variant10 of the plan, prepared by the same author, more clearly reflects the splendor of the residential city of the Saxon electors and kings of the Republic on the banks of the Vistula. When evaluating the maps drawn by C. F. Hübner, one from 1732 should also be taken into account.11

The second book13 allows us a close-up view of Warsaw at the beginning of the reign of King August III is a geographical account by the Saxon cartographer Adam Friedrich Zürner (1679-1742). The cartographer's journey from

Dresden is the second largest city and also the capital of the Free State of Saxony. Dresden lies on both sides of the Elbe in the Elbe valley. The city was mentioned for the first time in 1206, but it was not until 1485, when Leipzig was divided, that it became the residential city of the Albertine Wettin dynasty. Under Frederick Augustus I (Augustus the Strong), Dresden experienced a flurry of building activity, which gave the old town its still visible architectural form.

It is thanks to the Saxon elector and his undertakings that the idea of using the natural potential of a place to its advantage came to fruition. The location of the royal and court estates on the edge and at the foot of the high Vistula slope was a unique image in Europe, and one that helped secure Warsaw’s reputation as a magnificent city, which could be viewed both from the river and from its eastern bank. If we recall the map of the city made by an anonymous cartographer in 1732 and travel by boat along the Vistula, we see from the south a wooded part of the escarpment intended as a habitat for the royal pheasants, where Natolin is situated today. We see the gilded helmets and the belvedere of Wilanów Castle, the silhouette of the royal court on Lake Czerniaków, and the royal pavilion on the top of Rabbit Hill (PL: Królikarnia or Królicza Góra). Continuing along the sandy bank of the Vistula, we reach the meandering section of the river, which directs our gaze to the monumental Ujazdowski Castle, preceded by a water channel surrounded by a radial arrangement of wooded paths. The theatricality of this sight does not seem to be accidental.

Although there were no direct connections between most of the sites and residences on the slope in terms of their design, their close proximity, combined with the topography of the Warsaw escarpment and sub-steppe, allowed each to be seen from the others. This was not insignificant for the monarch's propaganda policy, which played an important role in the case of the Royal Pavilion built on Rabbit Hill in Czerniaków at the time of the Great Campaign in 1732.17

The period of flourishing urban development bestowed upon the city by the Saxon electors lasted until the end of the 18th century and was supported by King Stanisław August Poniatowski.A cartographic representation of Saxon Warsaw at the height of this boom, illustrating the development of Saxon architectural thinking, is the plan by Pierre Ricaud de Tirregaille (1725-1772) and its later versions.18 The engraved version of the map, supplemented with a city panorama seen from Praga (on the eastern bank of the Vistula), was published in 1762 shortly before the death of King August III.19

The patronage of the Saxon electors as kings of the Polish-Lithuanian Republic, which lasted for over 60 years, was an important historical period for the history and landscape of Warsaw. The traces of the cultural and artistic phenomenon known as "Dresden Baroque", which can still be found in the cultural landscape of the city today, deserve to be rediscovered. The prevailing historiography has, over many years, led to a permanent distortion of many facts and, as mentioned above, a devaluation of the role of Saxon patronage in culture and art.25 The history of Warsaw in Saxon times, which is partly recorded in the plans and maps cited here, is also the history of Dresden. For example, August the Strong’s experience of the buildings and architectural solutions of Warsaw from the end of the reign of Jan III Sobieski (such as the royal representative and business house of Maria Kazimiera Sobieska, called Marywil26)was the inspiration for the construction of the palatial Zwinger complex in Dresden.27 Also significant was August II’s inspiring encounter with Polish architecture, which in the middle of the 17th century was characterized mainly by architects of Italian and Dutch origin, primarily the famous Tylman of Gameren28, who is considered the Warsaw architecture teacher of August II.29 The topographical peculiarities of the city on the Vistula inspired the imagination and architectural ambition of August the Strong and gave hope for the realization of projects that would have been either impossible or very difficult to accomplish in the heavily fortified Dresden. An indisputable measure of the city-building power of the reign of August the Strong, August III, and the Warsaw magnates is the information contained in the tax registers and tariffs of the Warsaw estates.30

According to the data contained in them, between 1700 and 1734 there were 24 palaces and about 58 manor houses and country estates in the suburbs of the so-called Old and New Warsaw. By 1743, according to the tax records, there were already around 40 palaces, 8 small castles and about 136 manor houses and smaller residences in the area. The Vistula-influenced Dresden Baroque, regardless of how we might evaluate the consequences of the policies of August the Strong and August III, is the most beautiful and mature fruit of the Polish-Saxon Union.31 On the other hand, the picture of Warsaw presented here is proof that the Warsaw of the Enlightenment and the artistic patronage of the last king of the Polish Republic, Stanisław August Poniatowski, were the direct beneficiaries of the obsessive and visionary splendor of the Wettin court. Today, in a time of great geopolitical crisis, the Polish-Saxon Union with all its aspects also appears inspiring. Free from nationalistic tendencies, this historical union was a partnership based on mutual respect and mutual benefit.32