Nicolaus Copernicus was cautious about sharing his conviction that the planets rotate around the Sun, and only did so over the course of several decades. He was reluctant to cause a major turning point or revolution – and, initially, his teachings were not seen in this way either.

Text

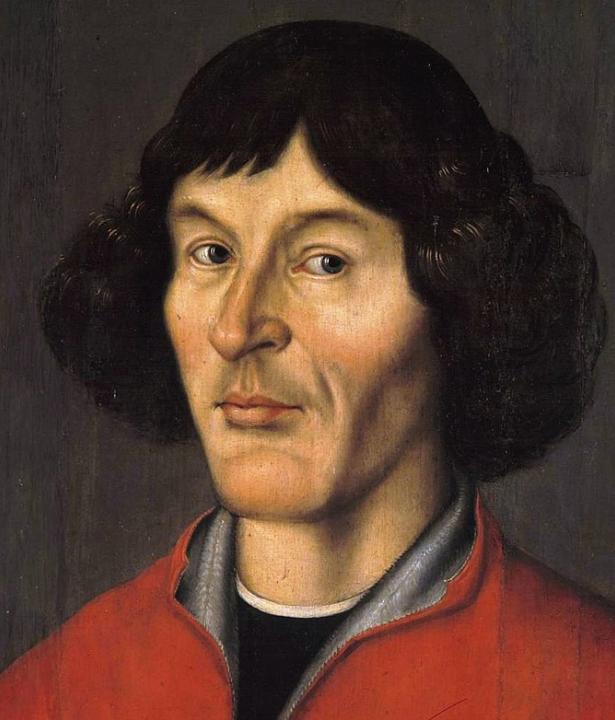

Nicolaus Copernicus, the man who is said to have started a revolution in the field of

cosmology

cosmology

the study of objects and matter outside the earth's atmosphere and of their physical and chemical properties

– nothing less than banishing the Earth from the center of the Universe – was first and foremost not actually an astronomer. At university, he was formally trained in canon law; he also studied medicine. His life was spent fulfilling administrative responsibilities for the church. But Copernicus came into contact with astronomy right at the start of his years as a student in Cracow, and he continued working intensively in this field until his death.

Text

The view of the world that was prevalent in 1500 – both in Europe and among Arab astronomers – dated back to the ancient Greek scholar Claudius Ptolemy, who lived in the second century AD. His teachings followed Aristotle’s principles: Ptolemy also placed the Earth at the center of the Universe, orbited by the planets. These so-called “wandering stars” were said to orbit the Earth along uniform, circular paths, attached to crystal bowls. Beyond this was said to be the sphere of fixed stars that remained immovable in relation to the planets. However, celestial observations did not seem to tie in with this uniform theory. In particular, the fact that the planets appear to retreat from the sky during certain parts of the year (known as retrograde movement) was not consistent with the Aristotelian ideal.

Text

The Ptolemaic System presented in the book Almagest, which provided the basic framework for astronomy up until the 16th century, answered these difficulties with a range of subtle corrections: The planets make smaller circular movements around their larger orbit as they travel along their path around the Earth (the epicycle). The Earth was moved slightly away from being the precise central point of the system and, instead, an additional imaginary point was defined (the “equant”), from which all the movements appear perfectly even. The geometric system meant that the positions of the planets could be predicted for any particular point in time and “rescued the phenomena”: i.e., actual astronomical observations no longer contradicted the core principles.

Text

Astronomers from the generations before Copernicus had already recognized the deficiencies of the Ptolemaic System, however. The accuracy of predictions occasionally left a little to be desired, and the notion that the planets didn’t orbit at equal speeds along the epicycles was deemed unsatisfactory from a philosophical point of view. It is not known exactly how, between 1508 and 1510, Copernicus came to the idea that the Sun should be placed at the center of the planetary system. This solution certainly didn’t arise from previously observed problems, and it is not known whether Copernicus was familiar with older heliocentric theories (e.g., those of the ancient Greek astronomer Aristarchus of Samos).

Text

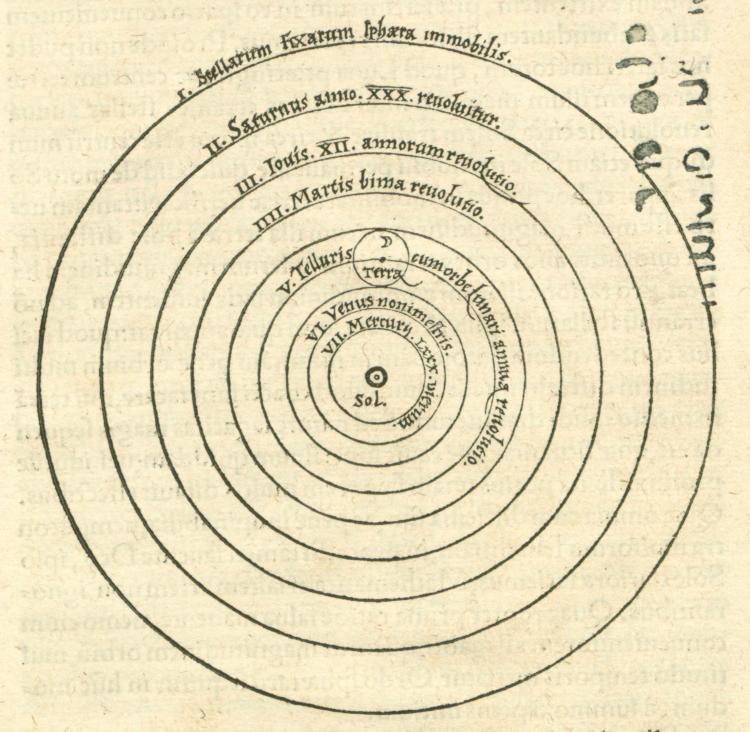

There is proof of the existence of a piece of writing by Copernicus from 1514 – the so-called Commentariolus (Little Commentary) – a copy of which was first discovered in the 1870s. Copernicus did not publish this treatise. It is believed he passed on short excerpts to some of his close friends and to other astronomers. In the Commentariolus, Copernicus explains that “many different phenomena in the sky” only stem “from the Earth”: With “its movement alone” being the cause. “The center of the Universe” is “near the Sun”: “Thus Saturn’s period ends in the thirtieth year, Jupiter’s in the twelfth, Mars’ in the third, and the Earth’s with the annual revolution; Venus completes its revolution in the ninth month, Mercury in the third.”1 This was the first description of the solar system.

Text

Copernicus refined this model over the following two decades. He worked on a large, seminal book entitled De Revolutionibus, but didn’t take steps to publish it. Nowadays, it is assumed that he feared embarrassment in front of scholars rather than possible opposition from the Catholic Church, as could be inferred from Rome’s later opposition to the Copernican teachings. Even when Copernicus’ only pupil, Georg Joachim Rheticus, published an initial report on the heliocentric model, the Narratio prima, in Danzig in 1540, it didn’t cause any unrest. Thanks to Rheticus’ hard work, Copernicus’ main work was published in 1543, just before his death, with a title not actually authorized by Copernicus: De revolutionibus orbium coelestium libri sex (On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres). Andreas Osiander, the editor who made this change, also added a note to the title page that described the contents of the book as hypothetical and something to aid astronomical computations.

Text

American Professor Emeritus of Astronomy and History of Science Owen Gingerich has proven that the first edition of De Revolutionibus was read by many scholars, including the Vatican astronomer Christoph Clavius. But, generally, the writing was seen as a “recipe book”2 for astronomy, as suggested in the note by Osiander, although the book contained an impressive graphical representation of the solar system. According to Gingerich, most 16th century astronomers thought that Copernicus’ greatest achievement was abolishing the notion of the equant. It was presumably hugely difficult for contemporaries to imagine the Earth upon which they stood as a moving celestial body when there was seemingly no evidence of this movement. This notion also contradicted the Bible, as Psalm 104:5 states: “Who laid the foundations of the Earth, That it should not be removed for ever.”

Text

But Copernicus and Rheticus understood this new illustration of the planetary system as absolutely real. Despite this, Copernicus didn’t see himself as a radical reformer. In contrast to later interpretations of his teachings, he didn’t knowingly formulate a counterargument to theology. This was recently pointed out by philosopher Jürgen Habermas in his extensive work This Too a History of Philosophy, which deals with the relationship between religion and philosophy. With a nod to Copernicus, but also to the astronomers Galileo Galilei and Johannes Kepler, who later followed in his footsteps, Habermas writes: „Die mithilfe von induktivem Verfahren und Experiment gewonnenen, mathematisch formulierten Naturgesetze drängen sich uns aus dem Rückblick als die markante Neuerung auf.“3 The „philosophische Selbstverständnis der großen Forscher und Entdecker“ still nonetheless operated „noch im Horizont der Überlieferung“4 : „Gläubige Christen waren sie alle. […] Diese Forscher machten keinen Versuch, die neue Konzeption der Naturgesetze vom christlichen Hintergrund ihres Weltverständnisses abzulösen.“5

Text

Prof. Andreas Kühne, science historian and co-editor of the Nicolaus-Copernicus-Gesamtausgabe (Nicolaus Copernicus Complete Edition), published in 2019 in Munich, claims that Copernicus was a conservative revolutionary, as he didn’t load the heliocentric world view with “implications for the status of people in society and the world.” In this respect, Copernicus himself was “no Copernican.”6

Text

English translation: LEaF Translations