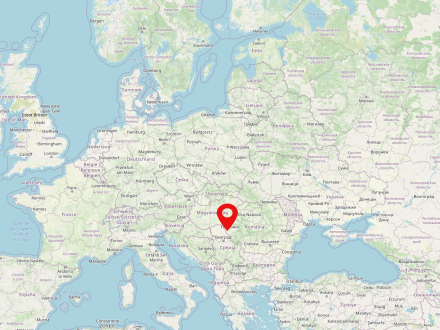

The village of Kölesd is located on the right bank of the Sió River about 150 km south of Budapest. Today the village is inhabited by about 1,500 people.

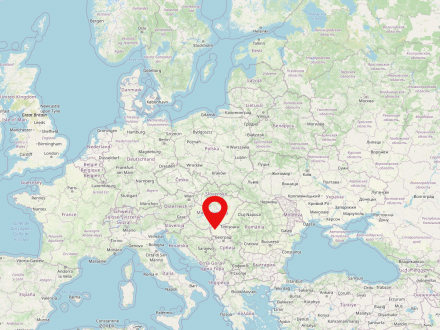

Tolna County was an administrative district in the west of the former Kingdom of Hungary and existed (with an interruption of one hundred and fifty years) from the Middle Ages until the 20th century. The seat of the county was initially Tolnavár, later Szekszárd.

In today's Hungary there is again a county Tolna with a population of over 223,000 inhabitants, the seat is again Szekszárd.

Szekszárd is a county seat in southwestern Hungary with over 33,000 inhabitants. The city is also the seat of Tolna County, an administrative district whose history - with interruptions - dates back to the 11th century.

The village of Kölesd is located on the right bank of the Sió River about 150 km south of Budapest. Today the village is inhabited by about 1,500 people.

Thirdly, he shall always grind good and enjoyable flour for the people, both local and foreign [...].

He should keep a watchful eye on [...] servants and boys, and not rely entirely on them, but keep a good watch over everything day and night, [...]. If the flour is spoiled and not milled properly, the master himself will be brought up to testify.

Corpus Iuris Hungarici 1000–1526

Just as the settlers come from different countries and provinces, so do they also bring with them different languages and customs, various useful objects and weapons, which adorn and glorify the royal court, but frighten foreign powers. A country that has only one language and one custom is weak and frail.

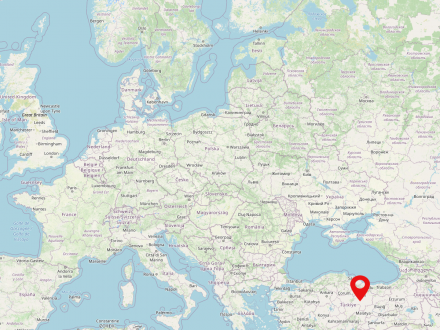

The Banat is a historical landscape located in South-Eastern Europe, in the states of Serbia, Hungary and Romania. The region is situated between the rivers Danube, Marosh and Tisza, as well as a southern part of the Carpathian Mountains and the lowland plain of Hungary. The main city of the Banat is Timișoara in Romania.

Bačka or Bácska is a geographical and historical area in the Pannonian Plain, bordered on the west and south by the River Danube and on the east by the River Tisza. It is shared between Serbia and Hungary. The larger part of the area is located in the Vojvodina region of Serbia, and Novi Sad, the capital of Vojvodina, is located on the border between Bačka and Syrmia. The smaller northern part of the geographical area lies within Bács-Kiskun county in Hungary.

Ofen (Hungarian Buda), today part of the Hungarian capital Budapest, was an independent city until 1873. It formed from the 13th century on the right bank of the Danube at the crossroads of important trade routes. It was the capital of the Kingdom of Hungary until the Ottoman Empire conquered it in 1541.

Vienna is the federal capital and the political, cultural and economic center of Austria. Around 1.9 million people live in the city alone, which is one-fifth of the country's population, and as many as one-third of all Austrians live in the metropolitan area. Historically, Vienna is particularly important as the capital and by far the most important residential city of the former Habsburg monarchy.

The Ottoman Empire was the state of the Ottoman dynasty from about 1299 to 1922. The name derives from the founder of the dynasty, Osman I. The successor state of the Ottoman Empire is the Republic of Turkey.

Kistormás is a village in Tolna County in southwestern Hungary. In the early modern period, German-speaking populations were deliberately settled here, coming from the Hessian region. Today the village has a little more than 300 inhabitants.