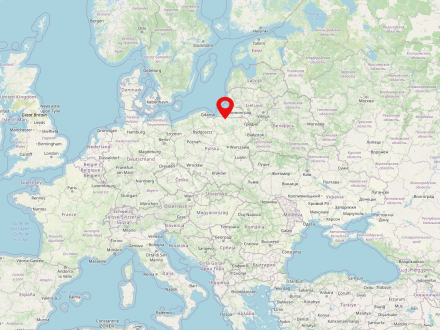

East Prussia is the name of the former most eastern Prussian province, which existed until 1945 and whose extent (regardless of historically slightly changing border courses) roughly corresponds to the historical landscape of Prussia. The name was first used in the second half of the 18th century, when, in addition to the Duchy of Prussia with its capital Königsberg, which had been promoted to a kingdom in 1701, other previously Polish territories in the west (for example, the so-called Prussia Royal Share with Warmia and Pomerania) were added to Brandenburg-Prussia and formed the new province of West Prussia.

Nowadays, the territory of the former Prussian province belongs mainly to Russia (Kaliningrad Oblast) and Poland (Warmia-Masuria Voivodeship). The former so-called Memelland (also Memelgebiet, lit. Klaipėdos kraštas) first became part of Lithuania in 1920 and again from 1945.

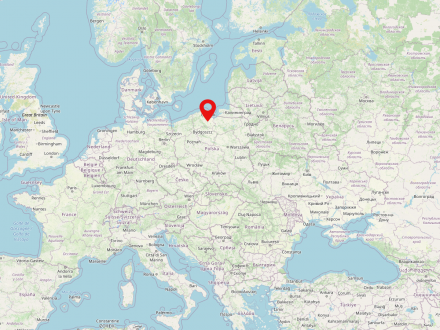

West Prussia is a historical region in present-day northern Poland. The region fell to Prussia as a result of the first partition of Poland-Lithuania in 1772 and received its name from the province of the same name formed by Frederick II in 1775, which also included parts of the historical landscapes of Greater Poland, Pomerania, Pomesania and Kulmerland. The Prussian province lasted in changing borders until the early 20th century. After World War I, parts fell to the Second Polish Republic, founded in 1918. The largest cities in West Prussia include Gdansk (Polish: Gdańsk, today Pomeranian Voivodeship), Elbląg (Polish: Elbląg, today Warmia-Masuria Voivodeship), and Thorn (Polish: Toruń, today Kujawsko-Pomeranian Voivodeship).

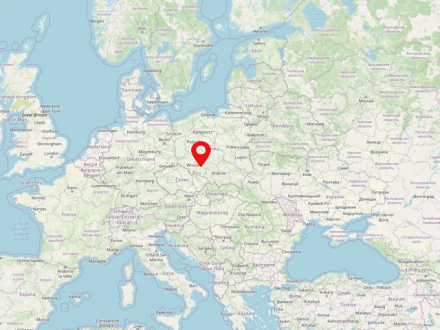

Silesia (Polish: Śląsk, Czech: Slezsko) is a historical landscape, which today is mainly located in the extreme southwest of Poland, but in parts also on the territory of Germany and the Czech Republic. By far the most significant river is the Oder. To the south, Silesia is bordered mainly by the Sudeten and Beskid mountain ranges. Today, almost 8 million people live in Silesia. The largest cities in the region are Wrocław, Opole and Katowice. Before 1945, most of the region was part of Prussia for two hundred years, and before the Silesian Wars (from 1740) it was part of the Habsburg Empire for almost as many years. Silesia is classified into Upper and Lower Silesia.

“Crowds of children came from the manors and the outlying farms to help distribute presents at Christmas. Many large bowls of dough had to be prepared. Already in October they would be placed in warm rooms to rise, and the contents of the dough that rose and expanded, full of life, came almost entirely [from the manor].”

“The winners then had to disclose their recipes. These were reviewed, compared, and expertly standardized. It became apparent that eight spices had been used the most. […] On the basis of this information, Robert May then produced a recipe booklet with baking instructions…This little recipe booklet was subsequently included with every packet of spices.”2

Kaliningrad is a city in today's Russia. It is located in the Kaliningrad oblast, a Russian exclave between Lithuania and Poland. Kaliningrad, formerly Königsberg, belonged to Prussia for several centuries and was the northeasternmost major city.

- 5g bitter orange peel

- 3g lemon peel

- 3g cinnamon

- 2g cloves

- 2g star anise

- 2g ginger

- 2g nutmeg

- 1g cardamom

“In the first year, we sold just 1,000 packets of pfefferkuchen spices [...] In the third year it was 10,000 and in the fifth year more than 70,000 packets, the contents of which found their way into the pfefferkuchen of families in the local area and beyond. A few years later, May’s pfefferkuchen spices were known throughout East and West Prussia, throughout Pomerania all the way to Berlin, and when, in late summer, the aroma of Staesz’s pfefferkuchen spices wafted along Wasser- and Schifferstraße as far as Elbląg Old Market, then the inhabitants of Elbląg would know that Christmas was just around the corner: the season had started.”3

- Natural honey will produce a particularly delicious flavour. Artificial honey is a poor substitute.

- You only need to warm the honey gently with sugar, and, if using, butter (fat). Spices should be added to the dissolved honey, and when it has cooled, this should be added to the flour and other dry ingredients.

- Baking powder, or ammonium bicarbonate (or cream of tartar) and potassium carbonate (or baking soda) may be used as raising agents.

- Raising agents should be diluted in rosewater, rum, lukewarm milk, or lukewarm water and then added according to recipe instructions.

- Baking paper is recommended for lining baking trays and tins.

- Always cut the gingerbread while it is still warm; once it has cooled, store in tightly sealed containers in a cool place.

- Bake in a preheated oven on the middle shelf at 180–220 °C.