The Ottoman Empire was the state of the Ottoman dynasty from about 1299 to 1922. The name derives from the founder of the dynasty, Osman I. The successor state of the Ottoman Empire is the Republic of Turkey.

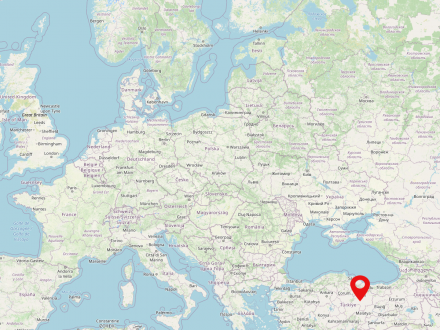

Istanbul (population, 2022: 15,244,936), formerly Byzantium, later also Constantinople, is located on the Bosphorus, the strait that connects the Black Sea with the Sea of Marmara which marks the border between Europe and Asia.

Today's megacity developed from the colony city of Byzantium which was founded around 660 BCE by Doric Greeks on the southwestern shore of the Bosphorus. Emperor Constantine I expanded the city and made it to the new capital of the Roman Empire. After the division of the Empire in 395, Byzantium was the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire. After its conquest by the Ottomans in 1453, it became the capital of the Ottoman Empire, initially as Constantinople.

Throughout its eventful history, and due to its location between two seas and continents, the city has been home to people of Muslim, Christian and Jewish religions, and has also experienced some of the largest waves of expulsions, particularly of non-Muslims of Armenian and Greek descent in the 20th century. Today, Istanbul is Turkey's most populous city and one of the largest in the world.

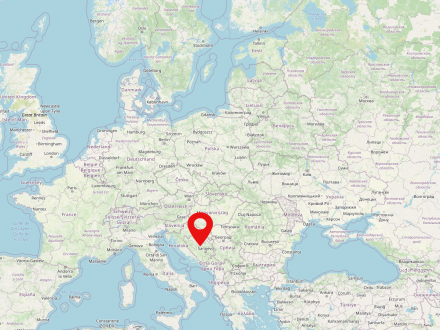

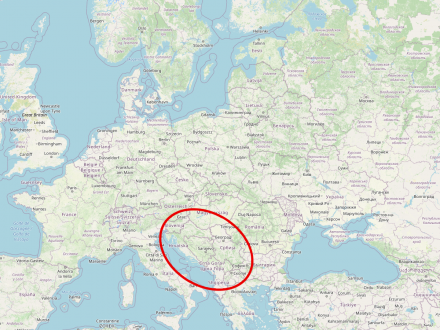

Bosnia and Herzegovina is a federal state in South-Eastern Europe. The country is inhabited by 3.3 million people and is composed of the political entities Republika Srpska, the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Brčko District. Bosnia and Herzegovina's capital is Sarajevo. The country is considered part of the Balkan Peninsula and borders the Adriatic Sea. Bosnians are the main population group, along with Serbs and Croats.

Sarajevo is the capital of Bosnia and Herzegovina. It is inhabited by about 290,000 people and is the only metropolis of the country.

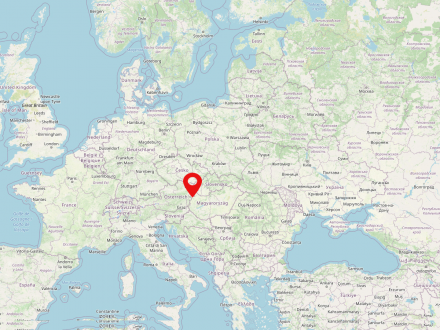

Austria-Hungary (Hungarian: Osztrák-Magyar Monarchia), also known as Imperial and Royal Hungary Monarchy, was a historical state in Central and Southeastern Europe that existed from 1867 to 1918.

Yugoslavia was a southeastern European state that existed, with interruptions and in slightly changing borders, from 1918 to 1992 and 2003, respectively. The capital and largest city of the country was Belgrade. Historically, a distinction is made in particular between the period of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia from 1918 to 1941 (also called 'First Yugoslavia') and communist Yugoslavia from 1945 (the so-called 'Second Yugoslavia') under the dictatorial ruling head of state Josip Broz Tito (1892-1980). The disintegration of Yugoslavia from 1991 and the independence aspirations of several parts of the country eventually led to the Yugoslav Wars (also called the Balkan Wars or post-Yugoslav Wars). Today, the successor states of Yugoslavia are Slovenia, Croatia, Serbia, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Kosovo and Bosnia and Herzegovina.

After an international competition in which 45 architects from a number of European countries participated, the Croatian-Jewish architect Rudolf Lubynski from Zagreb was chosen. Lubynski, who had studied in Karlsruhe, combined characteristics of German Reform synagogues of the early 20th century with the Orientalizing style of the 19th century.2 While preparing sketches of the building, he formulated his main idea as follows:

In this city that stands at the crossroads of Eastern and Western culture, which despite all the attacks of different actors and in different eras has been able to preserve its distinctiveness and special mentality for many years, [...] I have come to the conclusion that only a temple modeled on the spirit of the Moorish style, with the appropriate use of materials, modern construction and division of spaces, will fully correspond to the city, the location, the mentality and the purpose.3

The consecration was performed by the Grand Rabbi of Yugoslavia, Dr. Isak Alkalay, and the Chief Rabbi of Sarajevo, Dr. Moritz Levi. The building had taken four years to construct, and cost 18 million dinars.

The Sephardic temple on Kralja Petra Street, once one of the most beautiful synagogues in Europe, is now littered with straw, dung, and gasoline.4

After several years of construction, the adapted building designed by Ivan Štraus was reopened in 1965 as the "Đuro Đaković Workers' University". The architect redesigned the former sacral space as a cinema and concert hall with 854 seats.

The Workers' University was opened in December 1965 and, to commemorate the original use of the building as a synagogue, a monument designed by Zlatko Uglijen in the form of a menorah was erected in the courtyard:

In commemoration of the 400th anniversary of the arrival of the Jews in this region, their contribution to the development of our city, their participation in the struggle for national liberation, and their great sacrifices in World War II, this monument was erected in the temple, which the few surviving Jews gifted to their city.6