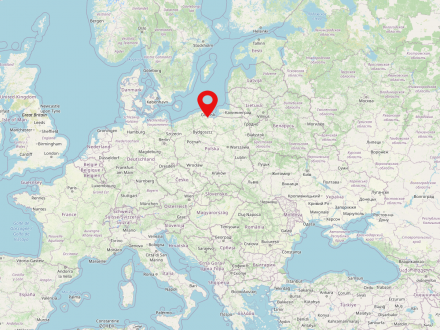

Gdansk is a large city on the Baltic Sea in the Polish Pomeranian Voivodeship (Pomorskie) with about 470,000 inhabitants. It is lying on the Motława River (German: Mottlau) on the Gdansk Bay.

The Teutonic Order state existed between 1230 and 1561 and covered parts of today's Baltic States, Poland, the Russian Federation (Kaliningrad Oblast), as well as today's Federal Republic of Germany. The Teutonic Order State was one of the few territorial manifestations of a knightly order in Europe.

The predecessor territories of the Kingdom of Poland were formed in the 9th and 10th centuries under the Piast dynasty. The kingdom was Christianized in the 10th and 11th centuries. In the 11th century, the monarchy was consolidated, whereby the kingdom was divided into several principalities in the 12th century, and from 1227 the seniority had only formal significance. In 1320, the principalities reunited to form the Kingdom of Poland. This kingdom entered into a personal union with Lithuania in 1386 and then merged with Lithuania in 1569 to form a real union.

In the 10th century, Poland was called Civitas Schinesghe (roughly "Gnesner Land"). Until 1025, partly in the 11th-13th century, the documents refer to the country as Ducatus Poloniae ("Duchy of Poland"). Between 1386 and 1795, the Kingdom of Poland was part of the dual monarchy of Poland-Lithuania.

As early as 1386, the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania were united by a personal union. Poland-Lithuania existed as a multi-ethnic state and a great power in Eastern Europe from 1569 to 1795. In the state, also called Rzeczpospolita, the king was elected by the nobles.

Royal Prussia is the name for those parts of the historical region of Prussia that fell from the ecclesiastical Teutonic Order to the Kingdom of Poland in the 15th century. These included large parts of Pomerania, including Danzig, Warmia and the Kulm region. The parts of Prussia that remained under the rule of the Teutonic Order formed the secular Duchy of Prussia in the 16th century, which fell to Brandenburg in 1618. It was not until the first partition of Poland-Lithuania in 1772 that Royal Prussia also came under Brandenburg-Prussian rule.

Stare Szkoty is today a district of Gdansk. It was founded as a village of Scottish immigrants, which the name reminds to this day.

The diocese of Kujawy and Pomerania has existed since the 12th century and has been renamed and restructured several times in the course of history. In today's Poland, it is the bishopric of Włocławek. The diocese is subordinate to the Archbishopric of Gniezno.

The Kingdom of Prussia existed from 1701 to 1918 and was reigned by the Hohenzollern dynasty. The country was an absolute monarchy from its founding until 1848 and a constitutional monarchy from 1848 until its dissolution. The capital of the Kingdom of Prussia was Berlin. The land was inhabited by about 40 million people. After the November Revolution of 1918 and the abdication of Wilhelm II, the Kingdom dissolved and formed the Free State of Prussia.

Nowe Szkoty (German: Neuschottland) was founded in the 16th century by Scots who arrived in Gdansk. Later Nowe Szkoty was incorporated by Gdansk.

Sosnowo is a small part of the municipality of Krynica Morska on the Vistula Spit.

The Duchy of Prussia lay between the lower reaches of the Vistula and Memel rivers. The capital of the duchy was Königsberg. The Duchy existed from 1525 - 1701, it was founded by the former Grand Master of the Teutonic Order and took in many Lutheran refugees from Poland-Lithuania. The Duchy of Prussia is considered the first principality of the Lutheran faith. Until 1657, the Duchy was a fief of the Polish Crown.

This happened in 1520, 1576, 1656 and finally in 1807, when Napoleon's army besieged and conquered Gdansk. Wealthy immigrants, on the other hand, found it easier to gain a foothold in their new surroundings. An important step in this process was gaining citizenship, which, among other things, allowed them to have a certain political say. Those who wanted to become citizens of the city of Gdansk usually had to pay a certain sum of money and also hope for the approval of the ruling councilors. At that time, on average, only about every fourth inhabitant of the city obtained this right. Historical research has shown that between 1558 and 1709 at least 135 people from Scotland were granted the status of citizens. The proportion of immigrants was thus still below the general figure. Nevertheless, quite a few of them were able to participate in public life in the city. For the economically better off merchants, the rich port city offered favorable conditions. After 1707, when the kingdoms of Scotland and England united, more and more people of Scottish origin from Gdansk traded under the umbrella of Great Britain.

Beyond the professional realm, the practice of religion also played a central role. Several churches opened their doors to Scots of the Reformed faith, in particular, the Church of St. Peter and Paul (Fig. 3) and the Church of St. Elizabeth. From the end of the 16th century on, both churches saw their congregations of immigrants grow noticeably – they had their own preachers and organized their own poor fund – and settlers even came from the surrounding villages and towns to Gdansk to be baptized and married here. During the 1640s and 1650s, these churches saw record numbers of baptisms and marriages of people of Scottish origin. The subsequent decline in the number of weddings, however, suggests that the descendants of the settlers became less and less culturally separate and intermingled with the native inhabitants of Gdansk. There is evidence, for example, that between 1580 and 1784 no fewer than 114 boys of Scottish background attended the academic grammar school, which was the most prestigious educational institution in the city at the time.