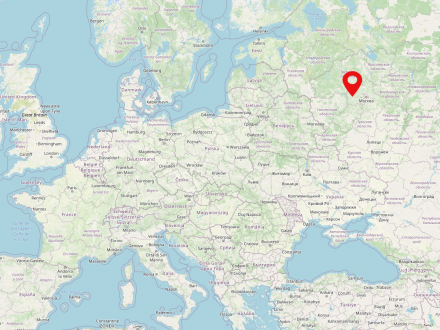

The Russian Federation is the largest territorial state in the world and is inhabited by about 145 million people. The capital and largest city is Moscow, with about 11.5 million inhabitants, followed by St. Petersburg with more than 5.3 million inhabitants. The majority of the population lives in the European part of Russia, which is much more densely populated than the Asian part.

Since 1992, the Russian Federation has been the successor state to the Russian Soviet Republic (Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic, RSFSR), by far the largest constituent state of the former Soviet Union. It is also the legal successor of the Soviet Union in the sense of international law.

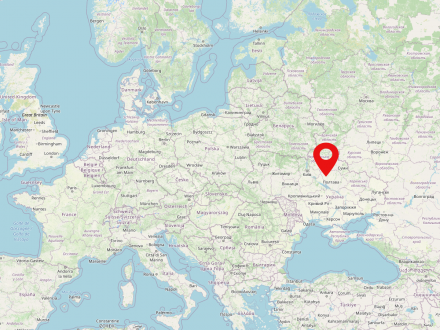

Ukraine is a country in eastern Europe inhabited by about 42 million people. Kiev is the capital and also the greatest city of Ukraine. The country has been independent since 1991. The Dnieper River is the longest river in Ukraine.

There is an evident imperative for academic decolonization (for the term, see below), particularly in Ukrainian and Eurasian studies, as these fields must disentangle themselves from the dominance of Russian influence. This decolonization extends not only to academic subjects but also to languages and the broader scientific framework.4

In the field of theory, established concepts such as "hybrid war" and "information war" are no longer entirely applicable, necessitating a conceptual reconfiguration. This shift is essential to accommodate the evolving nature of conflicts and their dynamics. It is more pertinent to consider contemporary conflicts as manifestations of colonialism, particularly evident in the context of Russian colonialism.13

The war is also changing the requirements profile and working structure of the historical sciences and raises questions about the authenticity of data and the decolonization of data cultures and digital infrastructures. “Data are never objective and free from bias or ideological convictions, just like historical sources. Data convey conflicts, hegemonies, and colonialisms. They reinforce cognitive biases and subaltern positions […]. One requires appropriate methods and tools not only to critically reflect on these inherited legacies and burdens, but also to bring our new awareness of them back into the research cycle”16. Already in 2020, Susan Drucker and Russell Chun17 pointed out the impact of fake news and disinformation campaigns on entire societies: “As does cancer, fake news hijacks the normal networks that power communication to spread, infect, and mutate. […] the onslaught and speed of potentially untrue, incorrect, or fabricated information (some crafted and weaponized, some carelessly shared), can cause a loss of our intellectual health. If we fail to have a common truthful basis for discussions of opinion, the integrity of our entire community suffers.”

Against this backdrop we should therefore ask the following questions: What does this mean for digital source criticism in times of fragile facts? What form of digital agency can be observed and what does this mean for the status of classical historical research and curatorial tasks? How does the war influence current developments in the construction, networking, and self-understanding of infrastructures? How should we deal with traditional knowledge and collection orders? How can the historicity and ambiguity of categories and concepts be brought into research data structures? What guiding principles do we have for dealing with contested knowledge? And last but not least: what competencies do we need to foster in future scholars in the humanities?

Challenges include conducting field research during wartime conditions, managing sensitive data susceptible to exploitation by adversaries, navigating the realm of information warfare with its inherent trust issues, and acknowledging the unreliability of data emanating from occupied territories due to the absence of freedom of expression. The motivations of academics have also evolved, shifting from pure objectivity towards a spectrum encompassing roles akin to journalists and activists.31

All in all, academic research on Eastern Europe in Germany is still suffering from its systematic reduction and deconstruction in the aftermath of the Cold War32. Recently, there have been several impulses to strengthen research on Eastern Europe, primarily based on establishing a broader perspective. For example, it has been suggested that a German Historic Institute be set up in Kyiv. Similarly, the founding of the German Historical Institute in Warsaw in 1993 indicated a new focus within historical scholarship on Poland and East Central Europe33.