The estates are overgrown. The great physician, time,

Beds the pain in oblivion. Say it yourself,

Again and again crushed by the law

Of the great number, do you trust the whole?

Wenzel – poet and singer, was born in 1955 in the GDR, where he was widely known and loved for his self-willed waywardness.1 Like so many, after 1989 he found himself in a different, foreign country. One of his happy new experiences was his friendship with the theologian and political scientist Antje Vollmer (cross-reference to chapter Antje Vollmer). The two have been engaged in an intensive East-West dialogue for many years. When Vollmer began researching the story of Heinrich and Gottliebe von Lehndorff, Wenzel listened to her with fascination. The courage of the young couple who decided to resist Hitler inspired him to write a poem.

Wenzel reads:

“The Last Letters

For Heinrich and Gottliebe von Lehndorff

“The estates are overgrown. The great physician, time,

Beds the pain in oblivion. Say it yourself,

Again and again crushed by the law

Of the great number, do you trust the whole?”

Wenzel

"'The great physician, time.' Time heals some things, other things it does not. And it's also about not being happy with the law of large numbers, which I have to submit to in this society – always bowing to the majorities. I was fascinated by that. I was fascinated by the way this man forces himself, so to speak, to take action and rebels against the majority, both in the military and in society as a whole. That, to me, is an exemplary act."

Wenzel is particularly fascinated by the letters that Heinrich von Lehndorff wrote to his wife from prison. The farewell letter from September 3, 1944, the day before his execution in Plötzensee, literally took his breath away. Ten densely written pages, full of life, personal, and completely unheroic. During the GDR era, Wenzel had studied farewell letters in the archives written by resistance fighters, young people from the Jewish-Communist circle of friends around Herbert Baum. These are treasures for posterity that have received far too little attention.

Wenzel

"That someone knows crystal-clear that the next day he will no longer be in this world. What does he leave to his loved ones, to those close to him? Some also leave something to humanity at that moment. In ancient drama, there is this moment where Antigone, at the end of her life, addresses the city one last time. At the point where we say goodbye to this life, we all arrive at the same point – perhaps this is the only time when this happens. So, in that sense, these are documents about the core of the human being at the very end, when we are no longer feigning an ideology or stuck in a pose."

Heinrich von Lehndorff reflects on this moment in the face of death in his last letter: "A complete transformation takes place," he writes, "whereby one’s previous life gradually recedes completely, and entirely new standards apply." After the failed assassination attempt of July 20, 1944, his escape and arrest and a second failed escape, after the interrogations and torture, he looks back on what was: a short "happy life" of 35 years, seven of them spent with Gottliebe in

The village of Sztynort is located in the north of the Masurian Lake District on the Jez Peninsula between Jezioro Mamry, Jezioro Dargin and Jezioro Dobskie. Until 1928 the village was called Groß Steinort, then Steinort.

Why isn't their story in the schoolbooks? Wenzel asks.

Eloquently and in noble poses the victors

of the day arrange their business and write themselves

Into the headlines of the history books.

Only the silent grass knows more."

The ruling historiography is the historiography of the rulers. This thought, penned by Karl Marx, is still valid today, says Wenzel. So much, too much is hushed up – as a citizen of the defunct GDR he experienced this firsthand.

Wenzel

"History is always written by the victors, who instrumentalize the events, so to speak. I have experienced this firsthand with my own history; I grew up in the GDR for half of my life and here for the other half. And the false views – one could almost say lies – that are spread as a normal narrative about the GDR, are inaccurate. They’re so pejorative and only reflect West German interests and views. That's why if, God willing, there are still a few more generations to come on this earth, they will probably learn more about this time from literature than from official historiography.”

What interests him are individual fates, the blind spots of history. Like flight and expulsion. Wenzel himself is a refugee, his family was expelled from

Bohemia is a historical landscape in present-day Czech Republic. Together with Moravia and the Czech part of Silesia, the landscape forms the present territory of the Czech Republic. Nowadays, almost 6.5 million people live in the region. The capital of Bohemia is Prague.

The Krkonoše Mountains are a mountain range in the Polish and Czech part of Silesia. The highest peak of the Krkonoše Mountains is the Schneppe (Polish: Śnieżka, Czech: Sněžka) at 1603 meters.

"It exhales the longing of the jails.

Failed escapes. Abused

Loyalty. Unsuccessful rescues. What does it mean,

To sacrifice one's life? For what? And why?"

Wenzel conjures up scenes from Heinrich von Lehndorff's last weeks. For what and why does he sacrifice his life? How does the young, fun-loving nobleman become this serious, determined conspirator?

Wenzel

"There was a real naivety to him. He was a country lad at the end of the day. An aristocratic country boy who liked to play with the horses and enjoyed life. He grew up in a castle and appreciated the fact that he grew up on that privileged side of the world, so to speak. We know these types – “sunny boys” we would say today – they are funny, good-looking men, who are always lucky, who succeed in everything. Yes, why should they doubt the world? That only comes, the doubt only comes, when something happens that no longer agrees with one's own attitude. Naivety is destroyed by knowledge, by experience."

Ulla Lachauer

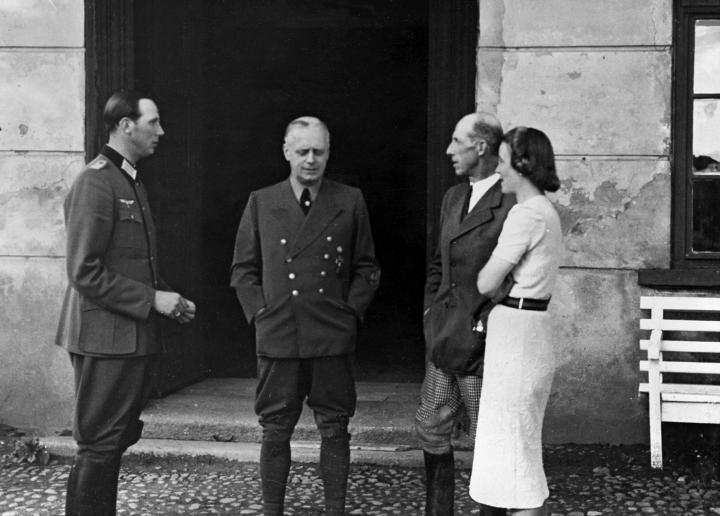

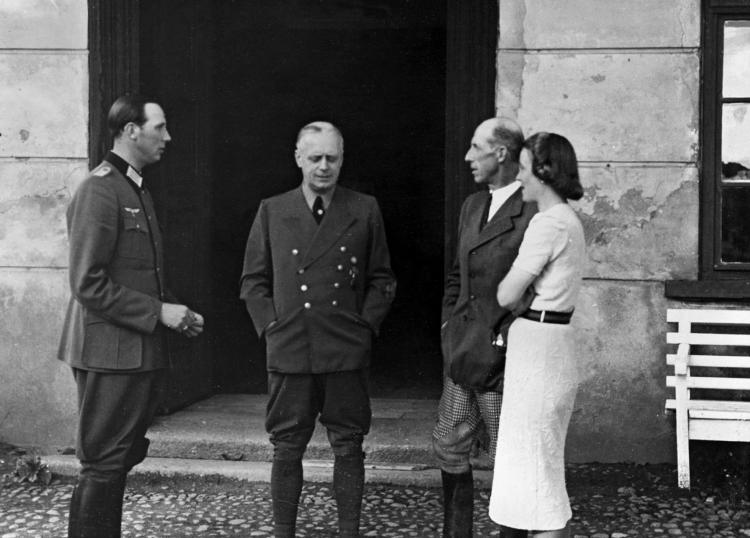

Experiences as an officer on the Eastern Front. As far as we know, it was the Borisov massacre in October 1941, where the SS murdered seven thousand Jews, that led Heinrich von Lehndorff to join the re-sistance. In addition, there was the experience of Gottliebe von Lehndorff, who endured life with her young daughters in Steinort Castle – under the same roof as Foreign Minister von Ribbentrop and his entourage.

"This is a fundamentally conspiratorial situation that they have entered into. There were also other resistance groups, also ones that preceded theirs, who tried to maintain a facade so that the conspirators could operate unnoticed. This requires permanent vigilance, so that no one makes a mistake, or is recognized in the wrong place. You have to lead a second life. It’s like living in the jungle, the dangers are lurking everywhere, and you must maintain this heightened attentiveness so that you don't put a foot wrong. For this, your whole nervous and sensory system has to be tensed – on high alert – which is always very good for a person. I think that's the kind of life she led, and of course it also made her incredibly attractive to her husband."

Ulla Lachauer

She, Gottliebe, led this double life with a cool head and a clear mind. Her feminine power of judgment informed the decision to act. It is likely that the couple made their key decision together.

In Königsberg Immanuel Kant disputed

Our power of judgment. That twentieth

Century, full of idols, money and prisoners,

dried this power for the herbarium of morals.

Wenzel sees the Lehndorffs' determination and decisiveness in the tradition of the enlightened philosopher Immanuel Kant. The poet was also fascinated by how the couple's love grew during the years of resistance.

Wenzel

"In the writings of Bertold Brecht, it's called "the third thing” – you know it when two people love each other, and then a third thing comes about, so to speak. I think that the strength of their love showed itself precisely in this situation – a love they had taken rather lightly before, because he was light-hearted. But then it showed itself when there was a plan to change something about this world that they thought was unjust. They were then able to move away from their self-centeredness. And it brought them closer; they had a secret from the world, like when you were a child and you knew a secret lake in the forest. In this way, they share a secret that they both guard. And they align themselves with it, give each other strength, and that elevates their love and makes it great."

In his farewell letter, Heinrich von Lehndorff speaks of this love. With tenderness and gratitude, he remembers their life together, "side by side". His sentences are meant only for Gottliebe and the daughters. He embraces them all, kisses the newborn Catharina, whom he will never know.

The truth is a pain

Born of the wakeful knowledge that comes from failing.

Wenzel's poetry captures a sense of pain and tragedy. In setting the poem to music, he adds a counterpoint: a light folk melody in waltz time.

Wenzel

(Sings) "Forgotten are the estates, tadatadem, that's like a little folk melody that could come from this landscape. Memories of childhood and the forests in East Prussia, a folk melody that I have there in a minor key, D minor. Padadampam, paditam, can also be sung differently, tadatadamtam, tadadidam, padampam, padadadampada. That was the intention, that this is a small modest folk song melody that becomes charged in relation to the somewhat more complicated text."

Ulla Lachauer

A simple, light melody that takes on the moods of Heinrich von Lehndorff’s farewell letter. It does not accuse, does not seem desperate. He lets his wife know that he does not fear death, that her love and God will carry him – to the very end.

The doomed man wants to comfort his family. A decision, says Wenzel, that also occurs again and again in poetry.

Wenzel

"There are always only two possibilities in poetry when you write something. Either one consoles or one contradicts. And in this letter, he doesn't resist anything, he consoles. It is a letter of consolation. The counteraction to this is the other attitude of standing up to or against the world. The consolation is that you give your strength to someone at that moment and say, now I’m not contradicting, I can't resist anymore, they're going to kill me, so instead I will console you."

Ulla Lachauer

What words does Gottliebe need for the period that will follow? So that she can live on and care for the children? Without "our dear Steinort"? Heinrich von Lehndorff wants to encourage his wife. He assures her again and again that he believes in her, not knowing whether his letter will even arrive.

The last letters foreshadow it like

The last swallows that presage the autumn.

Only at the end the world shines bright:

As the possible after the impossible.

"So much resonates in these words 'possible, impossible'. It's about openness, about the hope of an open future. This is what Lehndorff hopes for his wife. And he gives her carte blanche, assuring her that she can do anything and that he will always be with her. It is the model of paradise or eternity, of continued existence as the theology of liberation once described it. The people who were good in the world live are immortal because they live on in our memory. That is what liberation theology calls immortality."

Ulla Lachauer

The Nazis scattered his ashes on the fields outside Berlin. Nevertheless, Heinrich von Lehndorff lives on. His farewell letter remained a source of strength for Gottliebe until her death and still comforts his descendants to this day. In his poem, Wenzel quotes the last lines Heinrich von Lehndorff wrote in the margin.

I’m unhappy, because my heart

Still wants to tell you so much,

But paper and time have come to an end.

So you must think it.

"The rest you must think." Imagination, so to speak, opens the world beyond the nothingness of death. That's a great line. Yes, these are really great lines. It’s remarkable that he had the stamina to formulate these things at such length and to formulate them so precisely, in a very fine, I would say, aristocratic language. No carelessness, no complaint. If I were to publish a reader featuring special texts in the German language, I would include this letter."