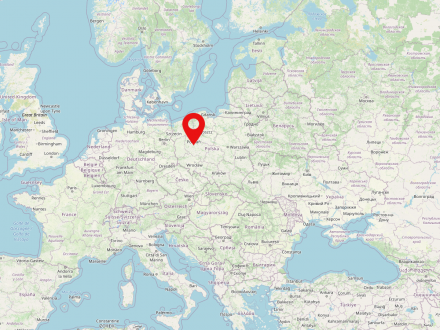

Poznań is a large city in the west of Poland and the fifth largest city in the country with a population of over 530,000. The trade fair and university city is located in the historic landscape of Wielkopolska and is also the capital of today's voivodeship of the same name. Already an important trade center in the early modern period, the city first fell to the Kingdom of Prussia in 1793 as part of the newly formed province of South Prussia. After a short period as part of the Duchy of Warsaw (1807-1815), Poznań rejoined Prussia after the Congress of Vienna as the capital of the new Province of Posen. From 1919, the city belonged to the Second Polish Republic for two decades, before it was occupied by the Wehrmacht in 1939 and became part of the German Reichsgau Wartheland (the so-called Warthegau). The almost six-year occupation period was characterized by the brutal persecution of the Polish and Jewish population on the one hand - tens of thousands were murdered or interned in concentration and labor camps -, and the resettlement of German-speaking population parts in the city and surrounding area on the other. In early 1945, Poznan was conquered by the Red Army and became part of the Polish People's Republic. One of the most important events of the post-war period was the workers' uprising in June 1956, which was violently suppressed.

These conflicting interpretations also had an impact on the cityscape, culminating in the construction of the so-called “Kaiserviertel” (Kaiser district) to the west. Contemporaries commented that the city was divided into a modern German Posen in the west and a traditional Polish Poznań in the east.4