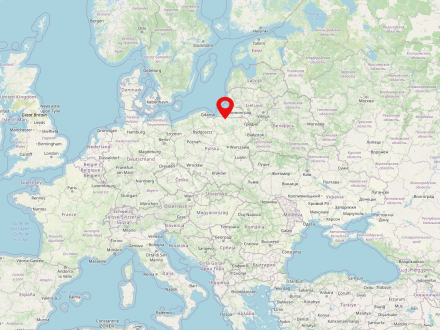

East Prussia is the name of the former most eastern Prussian province, which existed until 1945 and whose extent (regardless of historically slightly changing border courses) roughly corresponds to the historical landscape of Prussia. The name was first used in the second half of the 18th century, when, in addition to the Duchy of Prussia with its capital Königsberg, which had been promoted to a kingdom in 1701, other previously Polish territories in the west (for example, the so-called Prussia Royal Share with Warmia and Pomerania) were added to Brandenburg-Prussia and formed the new province of West Prussia.

Nowadays, the territory of the former Prussian province belongs mainly to Russia (Kaliningrad Oblast) and Poland (Warmia-Masuria Voivodeship). The former so-called Memelland (also Memelgebiet, lit. Klaipėdos kraštas) first became part of Lithuania in 1920 and again from 1945.

On a November day, the small suitcase lies on the living room table in Hanover.1 Tense silence, the locks snap open. The rayon lining is a vivid violet. The first thing that catches the eye is a songbook, and a pair of white knickers with something wrapped in them.

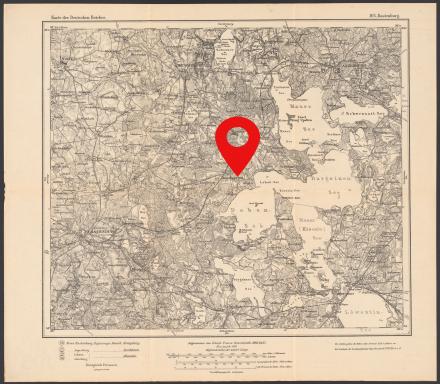

Radzieje, founded in 1417 as "Rosengarten" (“Rose Garden”), is a parish village in the Polish voivodeship Warmia-Masuria. Radzieje had 510 inhabitants in 2006.

They take turns telling the stories. "Look, the schoolhouse!" – "That was below the church." Effortlessly, they identify places and people in the photos. "Our grandpa!" Eva's father Heinrich Richard Puschke, the school's longtime principal. "Our grandma Gertrud." Eva's older brother Hans. "Our father, as a theology student." Sitting at the family coffee table, they also discover unfamiliar faces: "They must be the junior teachers."

And again and again "Aunt Eia" as a young woman. Pretty, often tomboyish.

The village of Sztynort is located in the north of the Masurian Lake District on the Jez Peninsula between Jezioro Mamry, Jezioro Dargin and Jezioro Dobskie. Until 1928 the village was called Groß Steinort, then Steinort.

Everyone had thought that the teacher dynasty ended with his retirement in 1938. So the discovery of the suitcase causes a small sensation in the family: he was not the last – his daughter Eva was. A woman!

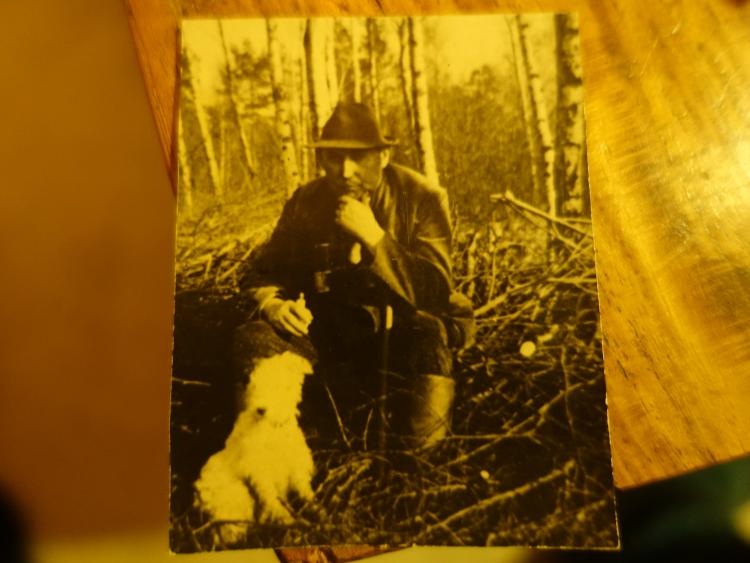

In the nieces' stories, the Rosengarten teacher's home comes to life. "Our grandpa, like all the Puschkes, was a great hunter." He was a true Masurian who hunted and fished, from a family that loved lakes and forests above all else. Music was also important, as was humor and the "typical East Prussian sentimentality." The men would drink hot grog together, play rounds of skat, and tell crude jokes known as "Wippchen" – these rituals all survived the expulsion.

The Puschkes became aware earlier than others that Hitler's war was lost. "Our father was a member of the Confessing Church." Hans Puschke, Eva's older brother, had been pastor in Nemmersdorf since 1936, after being transferred several times as a punishment. In the last winter of the war, his wife Käthe was pregnant with their sixth child, Eva-Maria.

Christiane Puschke only remembers a few blurred images of her family’s escape. A trailer pulled by a tractor full of children – she, then two and a half, her older siblings, her mother Käthe, and her Aunt Grete with her children.

Both families survived and were reunited in northern Germany. The trunk she’d escaped with accompanied Eva throughout her life, later becoming an archive. Her experiences of denazification, staying in makeshift emergency quarters, and searching for work are all documented; it will take months to piece everything together.

As the nieces grew older, they looked up to their single, working aunt as a kind of role model. "Eia was very different from our mother". Unconventional and funny, she had her own mind, smoked cigarillos, and drove a car, which was quite unusual for a woman back then.

Eva spent more and more time on a little patch of land she also called "Rosengarten". Many years before, she had leased the overgrown property near Haffkrug, in the Lübeck Bay. There was a one-room cabin with a bed and a stove with two hotplates, and an outhouse in front of the door. As early as March, she would drive there in her VW Golf, plant and tend her potatoes, pumpkins and cucumbers, strawberries, and roses, of course.

“Only once in her life did she have real money.” The nieces remember it like it was yesterday. “She won 77,000 marks playing Lotto.” That was in the mid-80s. She gifted a portion of her windfall to her nieces and nephews.

There are so many questions Eva-Maria and Christiane would ask their aunt today if they could: Did you ever go inside Lehndorff Palace? And did you ever talk to Gottliebe? Did you and your brother Hans ever fight? And was your father strict or lenient as rector?

As the letter reveals, Eva Puschke had applied for the position of governess for the four Lehndorff daughters. “The children are not learning anything at all at school, because it is too full and there are no teaching materials available. I am silently counting on you and making plans accordingly.”

The Lehndorffs and the Puschkes had once again crossed paths. But why nothing ever came of their plan to meet we don’t know. If Eva had taken up the position of governess, would she perhaps have also been happy as a teacher?