Monday, July 9, 1945: „Don't go to Kohlfurt! There’s no point. Trains don't run from there! We've been waiting for 14 days for a train to the West!“ That's what people told us when we started out on the road to Kohlfurt early in the morning with our luggage. We were told the same thing from all sides, but we wanted to try it in any case and bravely marched on. Along the way, we encountered a lot of Eastern workers who had to return to their country.1

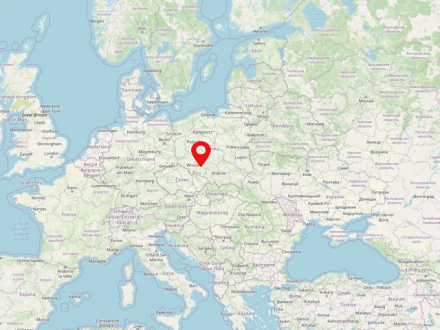

Silesia (Polish: Śląsk, Czech: Slezsko) is a historical landscape, which today is mainly located in the extreme southwest of Poland, but in parts also on the territory of Germany and the Czech Republic. By far the most significant river is the Oder. To the south, Silesia is bordered mainly by the Sudeten and Beskid mountain ranges. Today, almost 8 million people live in Silesia. The largest cities in the region are Wrocław, Opole and Katowice. Before 1945, most of the region was part of Prussia for two hundred years, and before the Silesian Wars (from 1740) it was part of the Habsburg Empire for almost as many years. Silesia is classified into Upper and Lower Silesia.

The town of Nowa Ruda is located in Lower Silesia in Poland and first appeared in official records in 1337. From the Middle Ages, textile production predominated in Nowa Ruda, and from the 19th century, mining became the most important economic sector. Today Nowa Ruda has almost 22,000 inhabitants.

The Lower Silesian town of Hirschberg, now Jelenia Góra in Polish, is located on the Bober River in the Hirschberg Valley at the foot of the Giant Mountains. It was an important trading center in the Middle Ages. A weaving industry was established here in the 16th century, followed by other industries. With the railroad connection in 1866, Jelenia Góra and the surrounding valley also became a popular tourist destination.

Thursday, July 5, 1945: Gritta got a fever again last night, so we stayed here today as well. She lay in bed all day. Mutti, Annemie [the acquaintance, editor's note] and I went into town to do some shopping. At the „Bürgerstübel“, we got a good vegetable soup using a voucher that we had taken from the refugee camp. Mutti and Annemie went to the hairdresser in the afternoon.6

Friday, July 6, 1945: When we started walking this morning, Mutti said: „From now on we'll be in the combat zone. We soon saw what she meant. The closer we got to Lauban, the greater the damage became. The roofs of a few houses along the road were torn off, the windows were broken, and telegraph wires were hanging down all tattered.7

Sunday, July 15, 1945: Yesterday we slept late and took a stroll through town. Today we went to a hotel for lunch at 12 o'clock. The waiter was so nice and gave us two lunches for one stamp. Annemie, Gritta and I went to the cinema at 3 o'clock: “Die Sache mit Styx”, a thriller starring Victor de Koroa [sic!]. Aue is a nice little town and has felt nothing of the war. People walk well dressed, and they even wear jewelry! We only see a few Russians, almost only officers.10

Material from the map collection of the Herder Institute

English translation: William Connor

Map mounting: Laura Gockert

Editing: Christian Lotz