As early as 1386, the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania were united by a personal union. Poland-Lithuania existed as a multi-ethnic state and a great power in Eastern Europe from 1569 to 1795. In the state, also called Rzeczpospolita, the king was elected by the nobles.

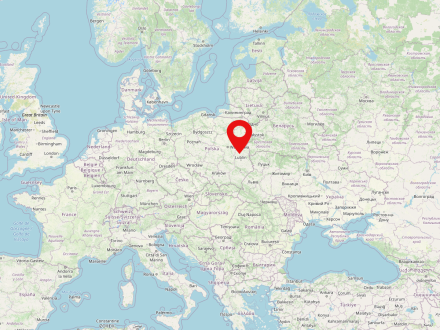

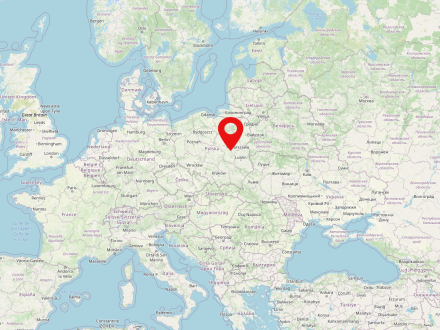

Kock is a small town in eastern Poland (population in 2022: 2,888), about 45 kilometers north of Lublin and 120 kilometers southeast of Warsaw. During the Third Partition of Poland (1795), Kock was occupied by Austria. In 1809 it was incorporated into the short-lived Polish Duchy of Warsaw. After the Congress of Vienna in 1815, it fell to Russia as part of the so-called Congress Poland. After World War I, when Poland regained its independence, Kock was part of the Lublin voivodeship.

In the 19th and in the first half of the 20th century several battles took place at Kock, including the last battle (October 2-6) of the regular Polish army after the German attack on Poland in 1939.

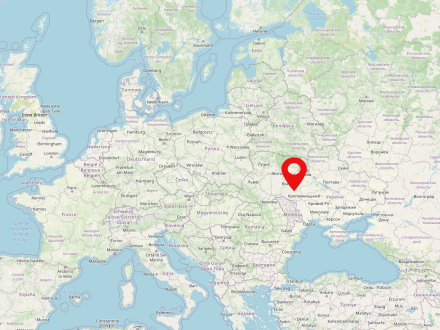

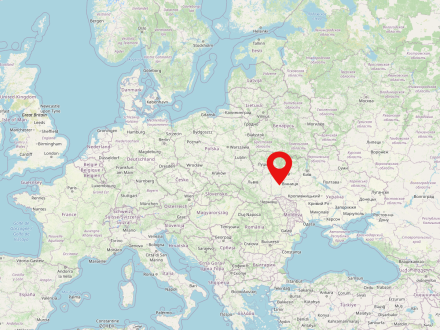

Bratslav is a settlement of urban type (population 2021: 4,872) in the Ukrainian oblast of Vinnytsia. It developed at a border fortress on the southern Bug River in the Principality of Galicia-Volhynia. Due to its location in an area contested by Poland-Lithuania in the west and the Tatar empires in the east, Brazlav was an important center of power in the Middle Ages and early modern period. In the 16th-18th centuries, the town was a voivodeship capital. Even before Magdeburg was granted city rights in 1569, Brazlav was an important center of Jewish life. Rabbi Nachman, the founder of one of the most important branches of Hasidism, worked here between 1802 and 1810.

After the destruction of the Great Northern War (1700-1721) and its incorporation into Russia during the partition of Poland-Lithuania, Brazlav gradually lost its importance.

Satu Mare is a major city in northwestern Romania. It is inhabited by 102,000 people and is located in the historical region of Sathmar. The city is located near the border with Hungary on the Someș River.

Belz is a small town (population 2021: 2,191) in Lviv oblast in western Ukraine, on the border with Poland between Solokìâ (a tributary of the Bug River) and its feeder Ričycâ.

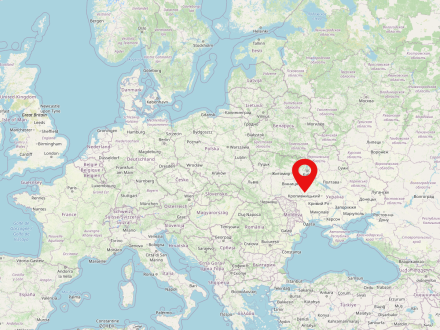

Uman’ (population 2021: 81,525) is the capital of the same-named rayon in Cherkasy oblast in central Ukraine. The city is located in the east of the historic Podolia region, on the banks of the Umanka River.

The city is a pilgrimage site for Hasidic Jews and an important center of horticultural research with the Sofiìvka Dendrological Park and the University of Horticulture.

The Essential Rabbi Nachman. (2006). Translated by Avraham Greenbaum. Jerusalem: Azamra Institute, p. 487.

“When my days are over and I leave this world, I will still intercede for anyone who comes to my grave, says the Ten Psalms, and gives a penny to charity. No matter how great his sins, I will do everything in my power, spanning the length and breadth of creation, to save him and cleanse him.”

Leżajsk is a county town (population 2022: 12.888) in the Subcarpathian Voivodeship in south-eastern Poland. In the First Partition of Poland (1772), Leżajsk was added to the Habsburg Empire and remained part of Austrian Galicia until 1918. In 1809, the city was absorbed into the Duchy of Warsaw, but was soon reclaimed by Austria. From 1918 the city belonged to Poland, which became independent again. Leżajsk is famous for the Bernadine basilica and monastery. Due to the tomb of Elimelech, the famous Hasidic Rebbe of the 18th century, the Jewish cemetery in Leżajsk is a popular pilgrimage destination for Jews from all over the world.

At the same time, these two important destinations should be seen as part of larger story, in which so-called “Hasidic routes” link several significant shrines. A good example is the route recommended by the Foundation for the Preservation of Jewish Heritage in Poland, which includes such destinations as

Lublin is a large city in eastern Poland. It is the capital of the voivodeship of the same name and is inhabited by just 340,000 people. Lublin is home to the prestigious John Paul II Catholic University of Lublin.

Dynów is a small town in Rzeszów County (population in 2022: 6,009) in Subcarpathian Voivodeship, Poland. It was first mentioned in written sources in 1423. After the First Partition of Poland (1772), Dynów was incorporated into the Habsburg Empire and remained part of Austrian Galicia until 1918. After the First World War, Dynów belonged to restored Poland, but lost its municipal rights, which it regained in 1947.

Łańcut is a town in south-eastern Poland with a population of 18,004. It is located in the Subcarpathian Voivodeship (since 1999) and is the capital of Łańcut County. In inter-war Poland, Łańcut was a county town administratively located in Lwów Voivodeship. Prior to the Second World War, Łańcut had a vibrant Jewish community, which made up about a third of the town's population.

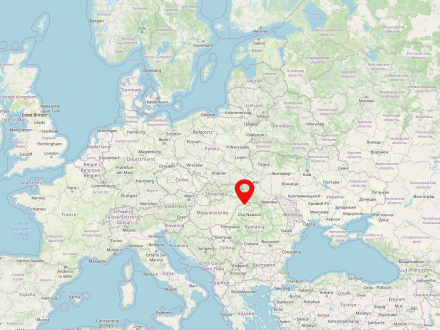

Medzhybish (population 2021: 1,237) is located in the western Ukrainian oblast of Khmelnytskyi. Shortly after being granted city rights in 1593, Medzhybish established itself as one of the most important trading towns in the eastern part of Poland-Lithuania, benefiting from its location close to the borders with Russia and the Ottoman Empire. However, its geographical location also led to numerous conflicts, which culminated in a period of Ottoman rule. In 1772, Medzhybish was annexed by Russia in the first partition of Poland.

Of its multicultural and multiethnic population (Poles, Jews, Ukrainians, Armenians, Greeks, Germans, Tatars), it was above all the Hasids who left a deep mark on the town. The founder of this mystical movement in Judaism, Israel ben Eliezer, and some of his students and later also Rabbi Nachman of Brazlaw worked here.

The decline that was already becoming apparent towards the end of the 19th century finally led to the town being downgraded to an urban-type settlement after 1924.