Bohemia is a historical landscape in present-day Czech Republic. Together with Moravia and the Czech part of Silesia, the landscape forms the present territory of the Czech Republic. Nowadays, almost 6.5 million people live in the region. The capital of Bohemia is Prague.

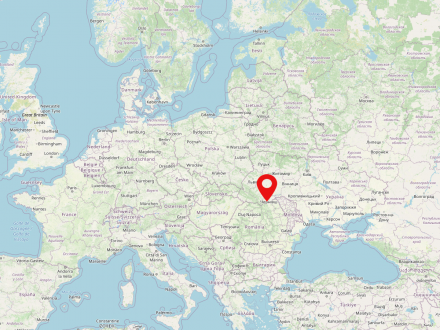

Galicia is a historical landscape, which today is almost entirely located on the territory of Poland and Ukraine. The part in southeastern Poland is usually referred to as Western Galicia, and the part in western Ukraine as Eastern Galicia. Before 1772, Galicia belonged for centuries to the Polish-Lithuanian noble republic, and subsequently and until 1918 - as part of the crown land "Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria" - to the Habsburg Empire.

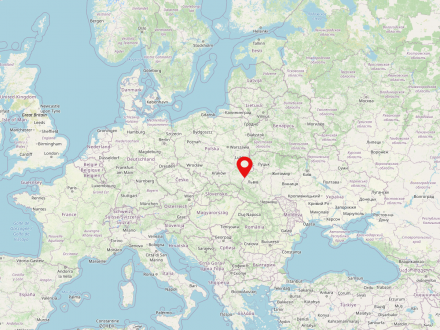

Bukovina is a historical landscape in modern Romania and Ukraine. The northern part is situated in the Ukrainian Chernivtsi Oblast, while the southern part is part of the Romanian Suceava County. The region once formed a part of the Principality of Moldavia and the Habsburg Monarchy.

The Russian Empire (also Russian Empire or Empire of Russia) was a state that existed from 1721 to 1917 in Eastern Europe, Central Asia and North America. The country was the largest contiguous empire in modern history in the mid-19th century. It was dissolved after the February Revolution in 1917. The state was regarded as autocratically ruled and was inhabited by about 181 million people.

The German Empire was a state in Central Europe that existed from 1871 to 1945. The period from its founding until 1918 is called the German Empire, then followed the period of the Weimar Republic (1918/1919-1933) and the National Socialism (so-called Third Reich) from 1933 to 1945. 01.01.1871 is considered the day of the foundation of the German Reich.

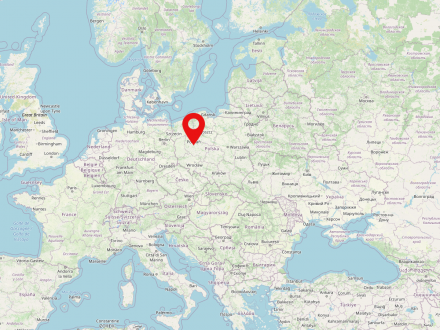

The historical province of Poznan was situated in eastern Prussia from 1815 to 1920. Currently, the territory of the former province is entirely in Poland. The capital was the city of the same name, Posen (present Poznań). About 2 million people inhabited the area.

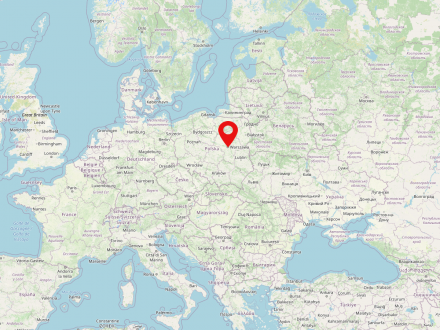

Warsaw is the capital of Poland and also the largest city in the country (population in 2022: 1,861,975). It is located in the Mazovian Voivodeship on Poland's longest river, the Vistula. Warsaw first became the capital of the Polish-Lithuanian noble republic at the end of the 16th century, replacing Krakow, which had previously been the Polish capital. During the partitions of Poland-Lithuania, Warsaw was occupied several times and finally became part of the Prussian province of South Prussia for eleven years. From 1807 to 1815 the city was the capital of the Duchy of Warsaw, a short-lived Napoleonic satellite state; in the annexation of the Kingdom of Poland under Russian suzerainty (the so-called Congress Poland). It was not until the establishment of the Second Polish Republic after the end of World War I that Warsaw was again the capital of an independent Polish state.

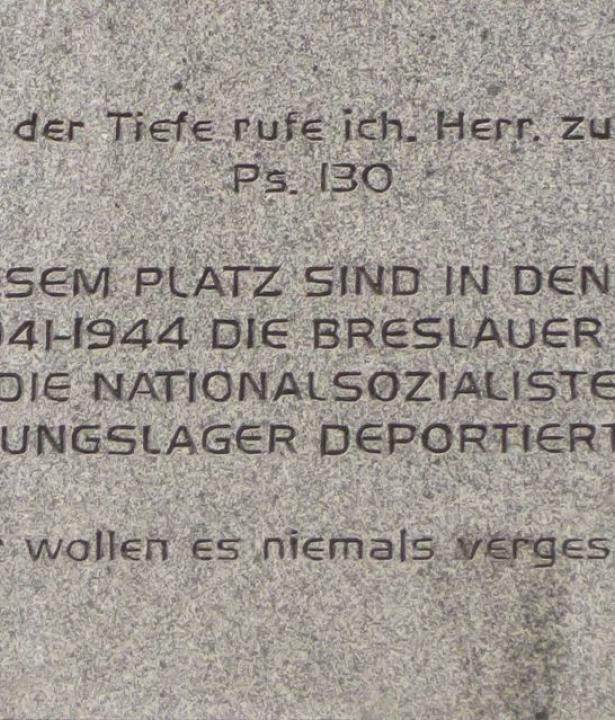

At the beginning of World War II, Warsaw was conquered and occupied by the Wehrmacht only after intense fighting and a siege lasting several weeks. Even then, a five-digit number of inhabitants were killed and parts of the city, known not least for its numerous baroque palaces and parks, were already severely damaged. In the course of the subsequent oppression, persecution and murder of the Polish and Jewish population, by far the largest Jewish ghetto under German occupation was established in the form of the Warsaw Ghetto, which served as a collection camp for several hundred thousand people from the city, the surrounding area and even occupied foreign countries, and was also the starting point for deportation to labor and extermination camps.

As a result of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising from April 18, 1943 and its suppression in early May 1943, the ghetto area was systematically destroyed and its last inhabitants deported and murdered. This was followed in the summer of 1944 by the Warsaw Uprising against the German occupation, which lasted two months and resulted in the deaths of almost two hundred thousand Poles, and after its suppression the rest of Warsaw was also systematically destroyed by German units.

In the post-war period, many historic buildings and downtown areas, including the Warsaw Royal Castle and the Old Town, were rebuilt - a process that continues to this day.

Poznań is a large city in the west of Poland and the fifth largest city in the country with a population of over 530,000. The trade fair and university city is located in the historic landscape of Wielkopolska and is also the capital of today's voivodeship of the same name. Already an important trade center in the early modern period, the city first fell to the Kingdom of Prussia in 1793 as part of the newly formed province of South Prussia. After a short period as part of the Duchy of Warsaw (1807-1815), Poznań rejoined Prussia after the Congress of Vienna as the capital of the new Province of Posen. From 1919, the city belonged to the Second Polish Republic for two decades, before it was occupied by the Wehrmacht in 1939 and became part of the German Reichsgau Wartheland (the so-called Warthegau). The almost six-year occupation period was characterized by the brutal persecution of the Polish and Jewish population on the one hand - tens of thousands were murdered or interned in concentration and labor camps -, and the resettlement of German-speaking population parts in the city and surrounding area on the other. In early 1945, Poznan was conquered by the Red Army and became part of the Polish People's Republic. One of the most important events of the post-war period was the workers' uprising in June 1956, which was violently suppressed.