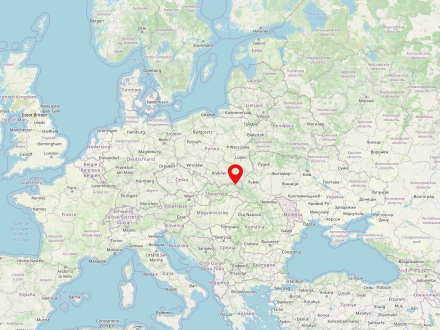

Zyndranowa (Ukrainian: Зиндранова) is a municipality in Podkarpacie Voivodeship in southeastern Poland. About 120 people live in the village. Zyndranowa is located in the Low Beskids Mountains in the municipality of Dukla.

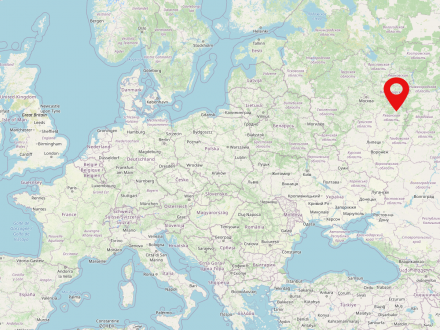

The Soviet Union (SU or USSR, Russian: Союз Советских Социалистических Республик, СССР) was a state in Eastern Europe, Central and Northern Asia existing from 1922 to 1991. The USSR was inhabited by about 290 million people and formed the largest territorial state in the world, with about 22.5 million square km. The Soviet Union was a socialist soviet republic with a one-party system.

The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic (Ukranian SSR, also UkrSSR, Ukrainian: Українська Радянська Соціалістична Республіка) was a union republic of the Soviet Union from 1922 to 1991. Founded in 1919, Kharkov was the capital of the USSR from its establishment until 1934, when it was replaced by Kiev until the demise (1991) of the USSR. About 51 million inhabitants lived in the USSR.

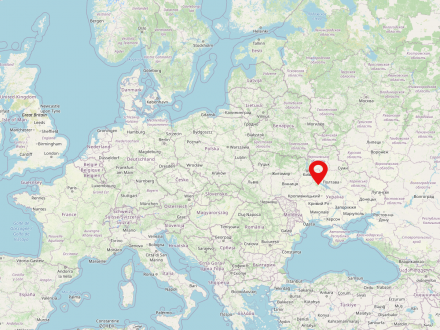

Silesia (Polish: Śląsk, Czech: Slezsko) is a historical landscape, which today is mainly located in the extreme southwest of Poland, but in parts also on the territory of Germany and the Czech Republic. By far the most significant river is the Oder. To the south, Silesia is bordered mainly by the Sudeten and Beskid mountain ranges. Today, almost 8 million people live in Silesia. The largest cities in the region are Wrocław, Opole and Katowice. Before 1945, most of the region was part of Prussia for two hundred years, and before the Silesian Wars (from 1740) it was part of the Habsburg Empire for almost as many years. Silesia is classified into Upper and Lower Silesia.

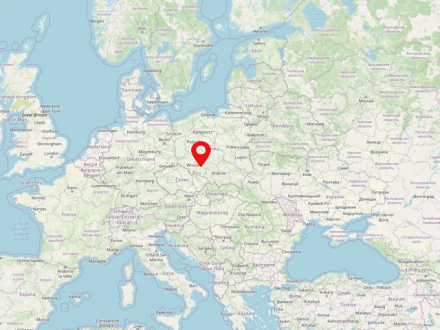

Legnica is a city inhabited by 99,000 people in the Polish voivodeship of Lower Silesia. The city is located in the west of the country not far from the capital of the voivodeship, Wroclaw. Legnica was part of the Prussian province of Silesia till 1945.