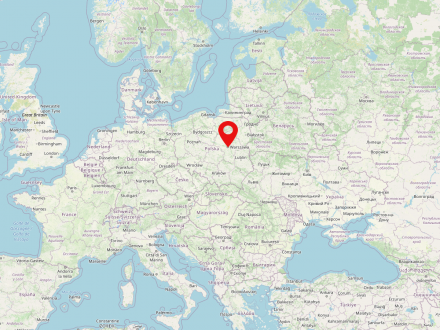

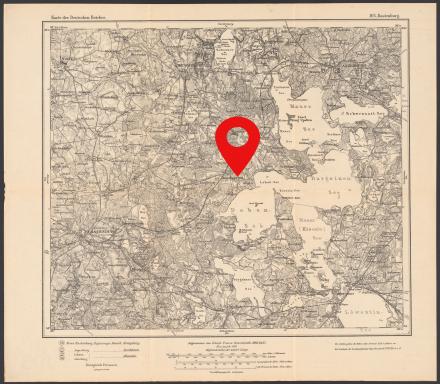

The village of Sztynort is located in the north of the Masurian Lake District on the Jez Peninsula between Jezioro Mamry, Jezioro Dargin and Jezioro Dobskie. Until 1928 the village was called Groß Steinort, then Steinort.

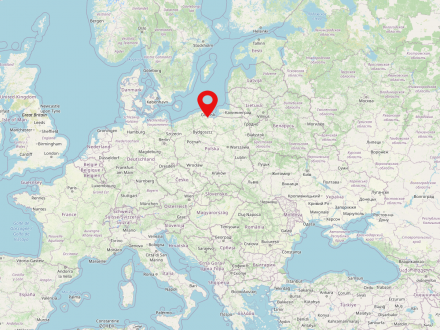

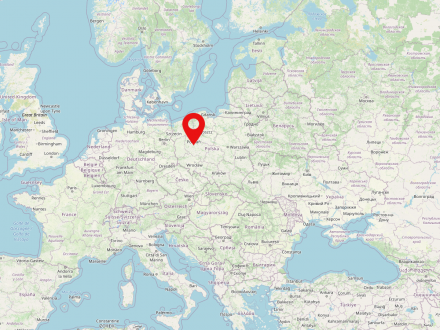

Giżycko is a town in the Polish voivodeship Warmia-Masuria. It was first mentioned in documents in 1340 as "Letzenburg" and "Lezcen". Giżycko is situated on an isthmus between the Jezioro Niegocin and the Jezioro Kisajno, a basin of the Jezioro Mamry.

In 2016 Giżycko had 29,642 inhabitants.

The picture shows a city view of Giżycko /Lötzen on a postcard from before 1945.

Sztynort fascinated her instantly. Everything that interested her as a social anthropologist seemed to be present in one town: a sailing port with a sociological history, a decaying Prussian noble residence, a village community in crisis. "An incredibly exciting intersection of themes."

As a young adult, Hannah Wadle had already discovered a love of the Polish language. Growing up in the Palatinate, on the French-German border, her parents were Western European polyglots. In order to distinguish herself, she became interested in the east, which seemed an enticing new territory after the eastward expansion of the EU.

Poland is a state in Central Eastern Europe and is home to approximately 38 million people. The country is the sixth largest member state of the European Union. The capital and biggest city of Poland is Warsaw. Poland is made up of 16 voivodships. The largest river in the country is the Vistula (Polish: Wisła).

People in the village were worried about her. From then on, the researcher felt a little like she belonged there. Shortly after this, she found accommodation with a kindly elderly couple, who took her in.

Little by little she learned what moved the people. At that time, there were 76 permanent residents living in Sztynort. Many were dissatisfied with the developments after 1989; they felt disconnected from the new market economy, aggrieved and deeply insecure.

The Pałac had been part of the socialist Sztynort. First perceived after 1945 as a remnant of a social enemy – a political legacy of Prussia and the feudal aristocracy – but it soon found a new purpose. It became the seat of the new power, the residence of the director of the PGR. It was also the social hub of the village, with a canteen, banquet hall, and cinema – a kind of people's palace, which also housed the local kindergarten.

The vacant Pałac, like the villagers themselves, had become the plaything of investors and politicians. A symbolic image of the lack of community life. There was nowhere to meet. Everyone struggled along on their own.

One small hope was the German-Polish foundation (https://deutsch-polnische-stiftung.de/), which took over the castle in 2010 with the help of its Polish sister foundation.

Many of the stories revolved around the "Zęza”, the harbor tavern, a meeting place for the sailing community from the early 1980s. It was a dingy, smoky vaulted cellar into which one descended as into the belly of a ship. They served beer and homemade pierogi, affordable for everyone. And everyone would drunkenly sing shanties together. Footage taken by a guest to the tavern in July 1993 gives a good impression of the atmosphere.

Hannah Wadle's heart goes out to them – the losers in this economic game. They’re the ones she’s interested in, also as a researcher. "We're sitting in a tourist landscape here," she says animatedly, "but the people here are, for the most part, shut out of it." She worries about the village. Over the years, she has turned from simply a listener to a committed participant in local affairs.

For the anthropologist, the "old Zęza" is a counter-concept, the antithesis to neoliberal capitalist transformation. And a source of inspiration for local visions of the future. Here and there they actually exist – one of the projects is a village fish restaurant. For many years, Hannah Wadle has followed with interest the journey of the gutsy local woman who is the entrepreneur behind it.

After the research year for her doctoral thesis was over, the anthropologist kept coming back.

She witnessed how the ailing castle suddenly became the center of new life and energy. She had often observed the German tourists. Bus passengers who, after visiting the Führer's headquarters “Wolfsschanze”, “Wolfsschanze”, The "Wolf's Lair" was built during the Second World War and was one of the "Führer headquarters". The facility, including bunkers and numerous buildings, was above ground but camouflaged in a wooded area near the town of Rastenburg (now Kętrzyn). Hitler stayed there mainly from 1941 to 1944. Today, the ruins of the Wolf's Lair, which was demolished by the Wehrmacht during its retreat, are a tourist attraction. wanted to see the aristocratic estate where Heinrich von Lehndorff, one of the conspirators of July 20, had his home. Or the cyclists who saw the palace as merely a stately backdrop for their picnics. But now activists entered the scene, the German-Polish Foundation, and the Lehndorff Society. In 2014, under the direction of Professor Wolfram Jäger of the TU Dresden, emergency work began to secure the castle and save it from irrevocable deterioration.

The next year the motto was "Spaziergang" (taking a stroll), referring to Antje Vollmer's "Doppelleben” (Double Life). One of the tours followed in the footsteps of Heinrich and Gottliebe von Lehndorff: excursions of the young lovers into the countryside, Sunday promenades to the teahouse, local places where their daughters would play. The escape route through the park taken by Heinrich von Lehndorff, after jumping out of the window on the morning of July 21, 1944.

"Palace in Progress" – the summer program is now entering its fifth year. Money is scarce, the project relies largely on donations. And on its volunteers: people from the village and the region, circles of friends from

Warsaw is the capital of Poland and also the largest city in the country (population in 2022: 1,861,975). It is located in the Mazovian Voivodeship on Poland's longest river, the Vistula. Warsaw first became the capital of the Polish-Lithuanian noble republic at the end of the 16th century, replacing Krakow, which had previously been the Polish capital. During the partitions of Poland-Lithuania, Warsaw was occupied several times and finally became part of the Prussian province of South Prussia for eleven years. From 1807 to 1815 the city was the capital of the Duchy of Warsaw, a short-lived Napoleonic satellite state; in the annexation of the Kingdom of Poland under Russian suzerainty (the so-called Congress Poland). It was not until the establishment of the Second Polish Republic after the end of World War I that Warsaw was again the capital of an independent Polish state.

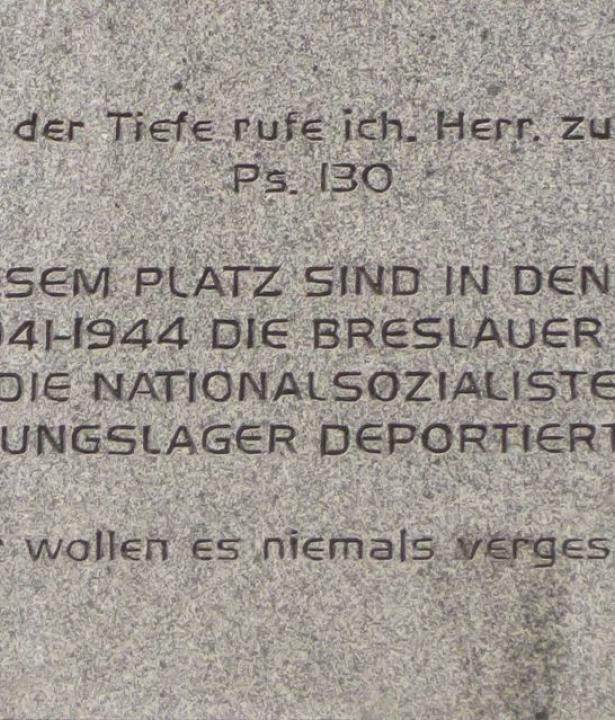

At the beginning of World War II, Warsaw was conquered and occupied by the Wehrmacht only after intense fighting and a siege lasting several weeks. Even then, a five-digit number of inhabitants were killed and parts of the city, known not least for its numerous baroque palaces and parks, were already severely damaged. In the course of the subsequent oppression, persecution and murder of the Polish and Jewish population, by far the largest Jewish ghetto under German occupation was established in the form of the Warsaw Ghetto, which served as a collection camp for several hundred thousand people from the city, the surrounding area and even occupied foreign countries, and was also the starting point for deportation to labor and extermination camps.

As a result of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising from April 18, 1943 and its suppression in early May 1943, the ghetto area was systematically destroyed and its last inhabitants deported and murdered. This was followed in the summer of 1944 by the Warsaw Uprising against the German occupation, which lasted two months and resulted in the deaths of almost two hundred thousand Poles, and after its suppression the rest of Warsaw was also systematically destroyed by German units.

In the post-war period, many historic buildings and downtown areas, including the Warsaw Royal Castle and the Old Town, were rebuilt - a process that continues to this day.

Gdansk is a large city on the Baltic Sea in the Polish Pomeranian Voivodeship (Pomorskie) with about 470,000 inhabitants. It is lying on the Motława River (German: Mottlau) on the Gdansk Bay.

Poznań is a large city in the west of Poland and the fifth largest city in the country with a population of over 530,000. The trade fair and university city is located in the historic landscape of Wielkopolska and is also the capital of today's voivodeship of the same name. Already an important trade center in the early modern period, the city first fell to the Kingdom of Prussia in 1793 as part of the newly formed province of South Prussia. After a short period as part of the Duchy of Warsaw (1807-1815), Poznań rejoined Prussia after the Congress of Vienna as the capital of the new Province of Posen. From 1919, the city belonged to the Second Polish Republic for two decades, before it was occupied by the Wehrmacht in 1939 and became part of the German Reichsgau Wartheland (the so-called Warthegau). The almost six-year occupation period was characterized by the brutal persecution of the Polish and Jewish population on the one hand - tens of thousands were murdered or interned in concentration and labor camps -, and the resettlement of German-speaking population parts in the city and surrounding area on the other. In early 1945, Poznan was conquered by the Red Army and became part of the Polish People's Republic. One of the most important events of the post-war period was the workers' uprising in June 1956, which was violently suppressed.

Radzieje, founded in 1417 as "Rosengarten" (“Rose Garden”), is a parish village in the Polish voivodeship Warmia-Masuria. Radzieje had 510 inhabitants in 2006.

But the people involved in these initiatives often feel like they’re sailing against the wind, and things are not getting any easier. The European crisis, the rise of nationalism, a pandemic that came out of the blue. Whether the former aristocratic palace will ever be finished, whether it will be able to reestablish itself as an important place for the village, for the voivodeship, for Europe, is uncertain. "A question of generations."

As a toddler, he explored all corners of the castle on the shoulders of his grandfather Jurek. As he grew older, he learned that his great-grandfather, a forced laborer from occupied Ukraine, had worked for Count Lehndorff in the horse stable in the 1940s.

Dawid tells the summer guests about this today. It’s yet another piece in the mosaic of European historical storytelling that Hannah Wadle dreams of.