The Russian Empire (also Russian Empire or Empire of Russia) was a state that existed from 1721 to 1917 in Eastern Europe, Central Asia and North America. The country was the largest contiguous empire in modern history in the mid-19th century. It was dissolved after the February Revolution in 1917. The state was regarded as autocratically ruled and was inhabited by about 181 million people.

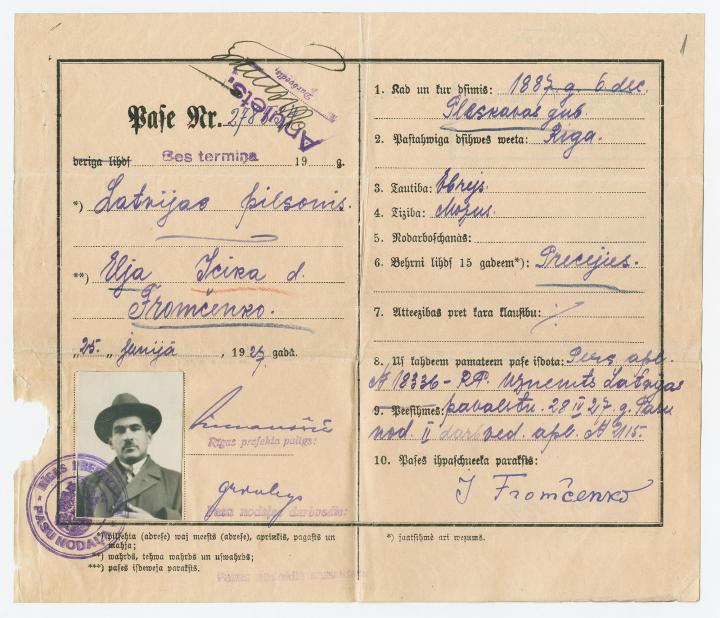

The capital of the new, democratic Republic of Latvia offered myriad opportunities for businesspeople and entrepreneurs. Latvia’s Jewish minority played a key role in reviving the country’s export and manufacturing sectors in the 1920s, which had suffered greatly during the war: the blockade of the Baltic had obstructed all trade, and in 1915 the Russian military administration had evacuated all industry out of Riga. Most of the machinery was never returned, so that after the First World War, Riga’s manufacturing sector had to start over virtually from scratch. Jewish entrepreneurs were central figures in the fledgling republic’s business world, owning 48% of commercial and 26% of industrial enterprises in 1925.3 So Laima was by no means exceptional among Latvian companies in the 1920s.

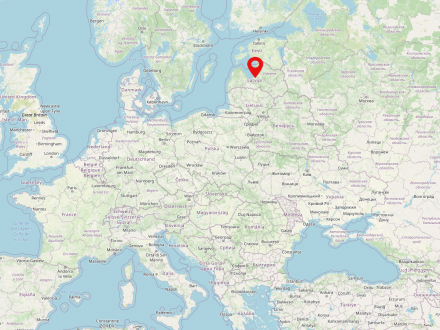

Pskov was first mentioned in 903, making it one of the oldest cities in Russia. Pskov was an important trading center and had a branch of the Hanseatic League. Under Peter I it was developed into a fortified city. Today, Pskov and the Pskov region are characterized by agriculture and handicrafts, and Pskov can be considered a religious center nationwide.

“the 23 Cases mentioned therein, duly arrived in good order, but landed at too high a cost to us on account of your increased price. This we recognise at the moment as something that cannot be helped, and we hope this will be remedied by your coming off the Gold Standard as Estonia has done. As things are at the moment, we are, strictly speaking not making on your lines, due to no fault of yours we admit.”10