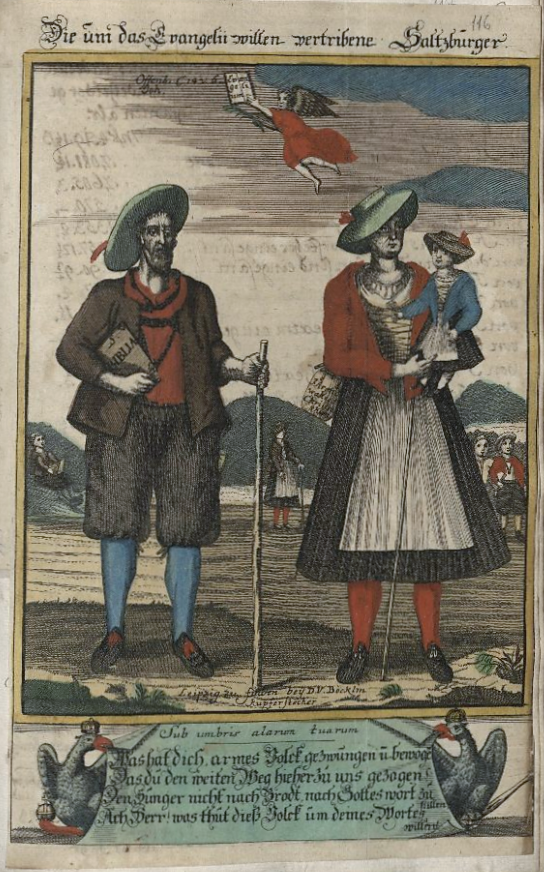

Migrations for religious reasons always touch the sphere of law; these are found in the context of the toleration, recognition, favoring and promoting or exclusion and persecution of certain religions. But they also have social and cultural effects on the migrants and on the post-migrant host society by triggering intercultural processes that influence collective identity and promote either tolerance or isolation. All of these processes are subject to change over the course of history.

Religious migrations have often become firmly rooted in the collective memory of the respective group. The exodus of the ancient Jews from the slavery of the Egyptian pharaoh under Moses' leadership, for example, is one of the central narratives of the “Tanakh“ “Tanakh“ The Tanakh, also referred to as the "Hebrew Bible", includes the books of the Torah, Nevi'im and Ketuvim. Its contents correspond to the Old Testament of the Christian Bible. 's origins and thus forms a basis of Jewish identity.2 Many Christian denominations, such as the members of the Armenian Apostolic Church or the Mennonites, also draw a sense of group consciousness from their historical persecution and diaspora situation.

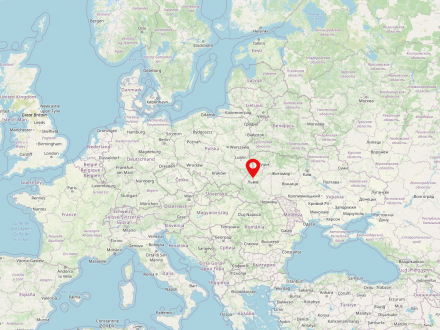

Krakow is the second largest city in Poland and is located in the Lesser Poland Voivodeship in the south of the country. The city on the Vistula River is home to approximately 775,000 people. The city is well known for the Main Market Square with the Cloth Halls and the Wawel castle, which form part of Krakow's Old Town, a UNESO World Heritage Site since 1978. Krakow is home to the oldest university in Poland, the Jagiellonian University.

Lublin is a large city in eastern Poland. It is the capital of the voivodeship of the same name and is inhabited by just 340,000 people. Lublin is home to the prestigious John Paul II Catholic University of Lublin.

Gdansk is a large city on the Baltic Sea in the Polish Pomeranian Voivodeship (Pomorskie) with about 470,000 inhabitants. It is lying on the Motława River (German: Mottlau) on the Gdansk Bay.

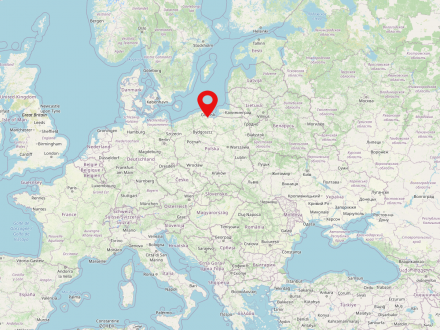

Royal Prussia is the name for those parts of the historical region of Prussia that fell from the ecclesiastical Teutonic Order to the Kingdom of Poland in the 15th century. These included large parts of Pomerania, including Danzig, Warmia and the Kulm region. The parts of Prussia that remained under the rule of the Teutonic Order formed the secular Duchy of Prussia in the 16th century, which fell to Brandenburg in 1618. It was not until the first partition of Poland-Lithuania in 1772 that Royal Prussia also came under Brandenburg-Prussian rule.

The Russian Empire (also Russian Empire or Empire of Russia) was a state that existed from 1721 to 1917 in Eastern Europe, Central Asia and North America. The country was the largest contiguous empire in modern history in the mid-19th century. It was dissolved after the February Revolution in 1917. The state was regarded as autocratically ruled and was inhabited by about 181 million people.

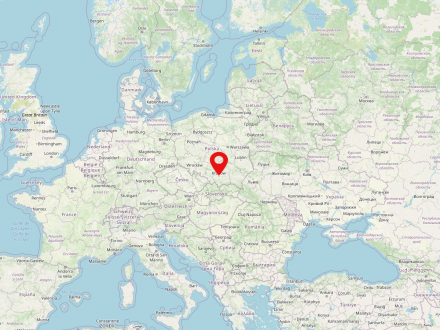

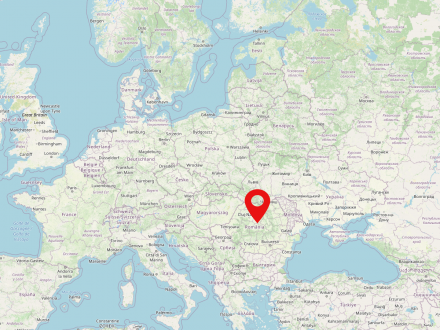

'Upper Hungary' (Slovak Horné Uhorsko, Hungarian hist. Felsőmagyarország, currently Felvidék) was the name of an administrative district created in 1541 and comprised the northeastern part of Hungary, which remained Habsburg. Even after its dissolution in the 17th century, the name survived and is still used in Hungary to name the geographical territory of present-day Slovakia, which is viewed critically in Slovakia itself.

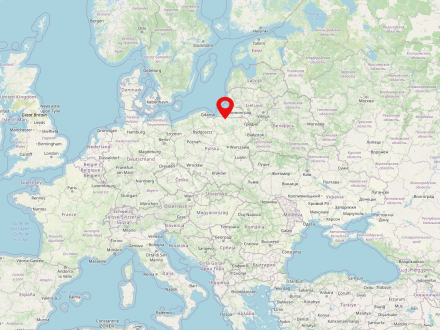

East Prussia is the name of the former most eastern Prussian province, which existed until 1945 and whose extent (regardless of historically slightly changing border courses) roughly corresponds to the historical landscape of Prussia. The name was first used in the second half of the 18th century, when, in addition to the Duchy of Prussia with its capital Königsberg, which had been promoted to a kingdom in 1701, other previously Polish territories in the west (for example, the so-called Prussia Royal Share with Warmia and Pomerania) were added to Brandenburg-Prussia and formed the new province of West Prussia.

Nowadays, the territory of the former Prussian province belongs mainly to Russia (Kaliningrad Oblast) and Poland (Warmia-Masuria Voivodeship). The former so-called Memelland (also Memelgebiet, lit. Klaipėdos kraštas) first became part of Lithuania in 1920 and again from 1945.

The village of Neppendorf (Romanian Turnișor) was founded in the Middle Ages by Transylvanian Saxon immigrants; later Protestant religious refugees from the Salzkammergut and Carinthia also settled here. Today Neppendorf belongs to Sibiu and is located halfway between the old town and the international airport.

Großau (Romanian Cristian) is a village with about 3,600 inhabitants in Transylvania, a few kilometers west of the international airport Hermannstadt/Sibiu. It is known for its fortified church and is one of the places in the region where, in addition to the Transylvanian Saxons who had settled here since the Middle Ages, Protestant religious refugees from the Salzkammergut and Carinthia settled, later also known as "Landler".

Großpold (Romanian Apoldu de Sus) is a village in Transylvania. It has about 1,450 inhabitants and is located a few kilometers northwest of Sibiu. Großpold is one of the places in the region where, in addition to the Transylvanian Saxons who had settled here since the Middle Ages, Protestant religious refugees from the Salzkammergut and Carinthia settled, who were later also called "Landler".

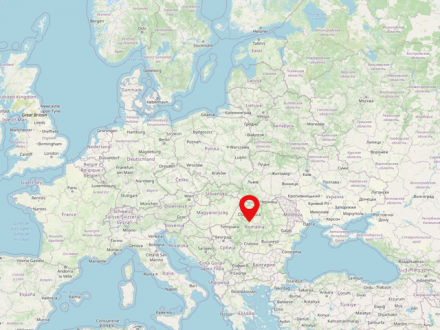

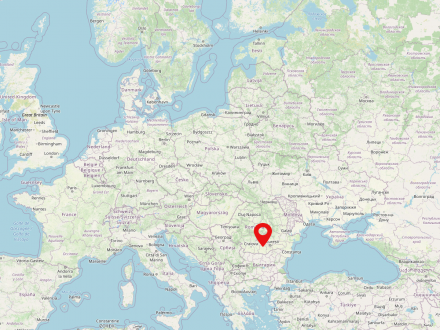

Transylvania is a historical landscape in modern Romania. It is situated in the center of the country and is populated by about 6.8 million people. The major city of Transylvania is Cluj-Napoca. German-speaking minorities used to live in Transylvania.

Hirschberg valley, a Silesian landscape rich in castles and monuments, became known as the "Silesian Elysium" in the middle of the 19th century and remained a touristic hot spot until the Second World War. Many of its towns and villages date back to the settlement by Germans in the 13th century. As early as 1305, 24 villages in Hirschberg valley were mentioned in documents, Hirschberg itself followed in 1355.

Mysłakowice (hist. dt. Zillerthal-Erdmannsdorf) is a municipality in southwestern Poland. Erdmannsdorf was first documented in 1305. In the 19th century, Erdmannsdorf castle was the summer residence of the Prussian king. In 1837, Frederick William III. left a large part of the estate to protestant refugees from Zillertal in Tyrol, wo founded their Tyrolean-style settlement "Zillerthal" there. In 1937, Erdmannsdorf and Zillerthal were joined together as municipality of Zillerthal-Erdmannsdorf.

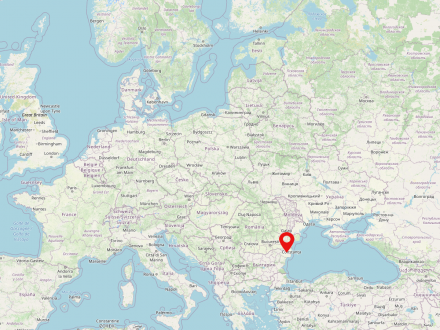

Dobruja (rum. Dobrogea, bulg. Добруджа) is a historical landscape in the border area between southeastern Romania and northeastern Bulgaria. Dobrogea is situated on the Danube and the Black Sea.

The Danube begins at the confluence of the Breg and Brigach rivers, whose springs are both located in the central Black Forest . It is 2857 km long and today flows through Germany, Austria, Slovakia, Hungary, Croatia, Serbia, Bulgaria, Romania, Republic of Moldova and Ukraine. Before it flows into the Black Sea, it fans out to form the Danube Delta, which is now an ecological reserve.

Vylkove is situated in the Danube Delta, on the Ukrainian side of the border with Romania. It was founded by Lipovans at the end of the 18th century.

Due to the war in Ukraine, it is possible that this information is no longer up to date.

Sarichioi is situated in the Dobrogea in Romania and belongs to the district of Tulcea. In the years 1654-1796, Lipovan religious refugees settled there.

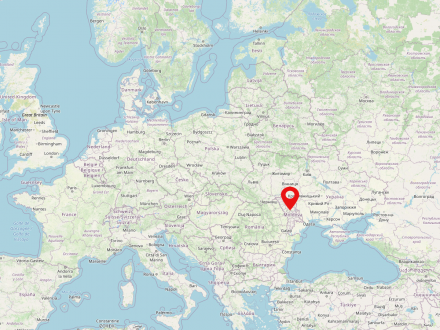

Romania is a country in southeastern Europe with a population of almost 20 million people. The capital of the country is Bucharest. The state is situated directly on the Black Sea, the Carpathian Mountains and borders Bulgaria, Serbia, Hungary, Ukraine and Moldova. Romania was established in 1859 from the merger of Moldova and Wallachia. Romania is home to Transylvania, the central region for the German minority there.

Crimea is a peninsula separating the Black Sea from the Sea of Azov. It is inhabited by nearly 2.3 million people. The capital is Sevastopol. The island is largely inhabited by Russian-speaking populations. Its status has been disputed under international law since 2014.

The term Moldova here applies to the historical landscape in today's Romania, which goes back to several historical states and provinces like the former Principality of Moldova. Moldova borders Bessarabia to the east and Bukovina to the north.

Wallachia is a historical landscape in the South of Romania, bordering the mountain range of the Southern Carpathians and the historical landscape of Transylvania in the North, the Danube River in the South and Bulgaria in the political sphere. The biggest city of Wallachia is the Romanian capital Bucharest.

Poland is a state in Central Eastern Europe and is home to approximately 38 million people. The country is the sixth largest member state of the European Union. The capital and biggest city of Poland is Warsaw. Poland is made up of 16 voivodships. The largest river in the country is the Vistula (Polish: Wisła).

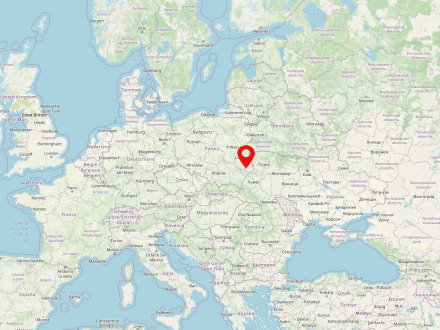

Lviv (German: Lemberg, Ukrainian: Львів, Polish: Lwów) is a city in western Ukraine in the oblast of the same name. With nearly 730,000 inhabitants (2015), Lviv is one of the largest cities in Ukraine. The city was part of Poland and Austria-Hungary for a long time.

Due to the war in Ukraine, it is possible that this information is no longer up to date.

Zamość is a city of 63,000 people in southeastern Poland. It is located in the Lublin voivodeship not far from the border with Ukraine. Zamość is located in the Roztocze region.

Elisabethstadt is a small town inhabited by 7,400 people in the historical region of Transylvania. It was founded in the Middle Ages by Transylvanian Saxons.

The Ottoman Empire was the state of the Ottoman dynasty from about 1299 to 1922. The name derives from the founder of the dynasty, Osman I. The successor state of the Ottoman Empire is the Republic of Turkey.

Today, people are still fleeing persecution and war for religious reasons, for example Christian and Iraqi Syrians or Shiite Muslims from predominantly Sunni areas in the Middle East. While the importance of religion is declining in many European countries, in other parts of the world, belonging to a particular religious group continues to be a criterion for exclusion.

Let us return once again to the initial question: The Canadian singer-songwriter Leonard Cohen came from a Jewish family whose ancestors emigrated to North America from Lithuania, then part of the Russian Empire. The ancestors of New York director Woody Allen also migrated to the USA from various Jewish communities in the Tsarist Empire and

Austria-Hungary (Hungarian: Osztrák-Magyar Monarchia), also known as Imperial and Royal Hungary Monarchy, was a historical state in Central and Southeastern Europe that existed from 1867 to 1918.

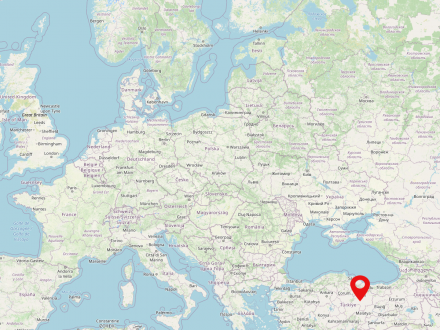

Georgia is a republic in the South Caucasus. The land is inhabited by 3.7 million people and is located on the border between eastern Europe and western Asia. The capital of Georgia is Tbilisi. The country is located on the eastern end of the Black Sea and borders Russia as well as Turkey, Azerbaijan and Armenia. Georgia has been an independent state since the fall of the Soviet Union.