The whole of Eastern Europe is a kind of Pompeii. This Pompeii fascinates not only those who have lost their homeland, but also those who have had it returned to them and are reassimilating here.1

The Krkonoše Mountains are a mountain range in the Polish and Czech part of Silesia. The highest peak of the Krkonoše Mountains is 1603 meters above sea level (Polish: Śnieżka, Czech: Sněžka).

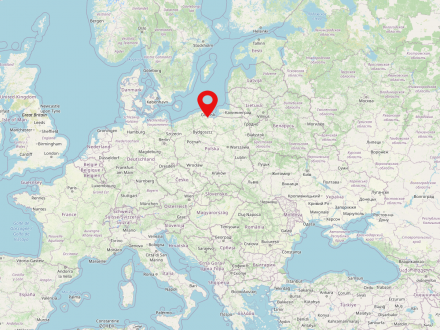

Gdansk is a large city on the Baltic Sea in the Polish Pomeranian Voivodeship (Pomorskie) with about 470,000 inhabitants. It is lying on the Motława River (German: Mottlau) on the Gdansk Bay.

Kaliningrad is a city in today's Russia. It is located in the Kaliningrad oblast, a Russian exclave between Lithuania and Poland. Kaliningrad, formerly Königsberg, belonged to Prussia for several centuries and was the northeasternmost major city.

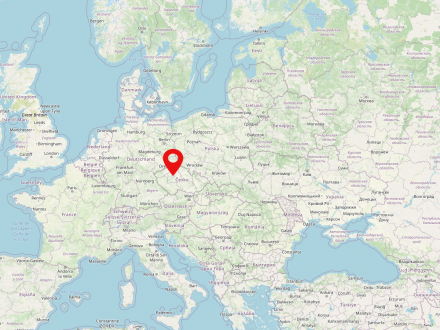

Prague is the capital of the Czech Republic and is inhabited by about 1.3 million people, which also makes it the most populated city in the country. It is on the river Vltava in the center of the country in the historical part of Bohemia.

Located in the southeastern part of the Czech Republic, Brno (tsch. Brno) is the second largest city in the country after Prague, with a population of about 380,000. It replaced Olomouc as the capital of Moravia in 1641. Today Brno is the administrative seat of the South Moravian Region (Jihomoravský kraj) and an important industrial, commercial and cultural center. The university city is the seat of the Constitutional Court and the Supreme Administrative Court of the Czech Republic.

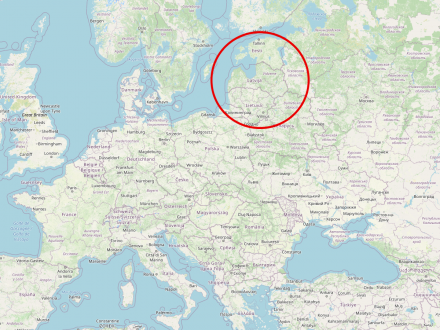

The Baltic States is a region in the north-east of Europe and is composed of the three states Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. The Baltic States are inhabited by almost 6 million people.

The village of Sztynort is located in the north of the Masurian Lake District on the Jez Peninsula between Jezioro Mamry, Jezioro Dargin and Jezioro Dobskie. Until 1928 the village was called Groß Steinort, then Steinort.

Secondly, there are memories of the later, post-war history of the Steinort estate, which, for example, focus on the kindergarten in Steinort Castle and, above all, on the arrival and integration of the Polish population after 1945. When Maria Zarębska speaks of Lehndorff, who was also present in narratives of the postwar years, the focus is not on the resistance fighter, but on the hegemonic role of the noble family and its head at the time: "He was a count, they said, very rich, and he owned many people."

The third chapter of Steinort history is probably that of the reconstruction work that has taken place since the turn of the millennium. It is the story of enthusiasts like Bettina Bouresh, Wolfram Jäger, Hannah Wadle or Marek Makowski and Piotr Wagner. Certainly, a romantic view also plays a role here, but what prevails is the sense of a shared desire to develop Steinort into a meeting place of Germans and Poles, where the diverse stories of the place are held.

The interview project has uncovered these diverse layers of Steinort's history. Hopefully it will contribute to making Steinort a living place of exchange and encounter, where people can engage with European history and stories in all their complexity. Last but not least, it is to be hoped that Steinort will indeed become a European place of remembrance with high identity relevance for various European societies.4